The government seems more committed than ever to reducing the UK’s greenhouse gas emissions. As buildings account for 40% of those emissions and that can be reduced using existing technology, it is not surprising targets for reducing the carbon footprint of buildings are tightening. One easy gain is with behind tile heating in conjunction with a heat pump.

In January the government published a 114-page response to its consultation on the Future Homes Standard, saying all new homes will be required to be ‘zero carbon ready’ by 2025. (You can download the response from bit.ly/netzeroco2.)

What ‘zero carbon ready’ means is that new homes will not have fossil fuel heating, such as a natural gas boiler, but will be future-proofed with low carbon heating and high levels of energy efficiency, so no retrofit work will be necessary to make the houses zero-carbon as the electricity grid continues to decarbonise.

The move away from gas heating will be significant, as nearly 83% of the UK housing stock is currently heated by gas, according to the BRE report The Housing Stock of the United Kingdom, last year.

One way of improving the energy efficiency of heating (and cooling) buildings is to use what used to be called underfloor heating (UFH), although it has moved on to become heating behind tiling on walls as well as floors. It is particularly efficient used in conjunction with the thermal mass of natural stone tiles, which retain and radiate heat.

Radiated heat is pleasant. It is warming at lower air temperatures than are usually achieved with conventional radiators, which, in spite of their name, do not actually radiate much heat but rely mostly on warming the air by conduction and circulating it by convection. It is the difference between standing on the sunny side of a street or in shadow, even though the air temperature in both locations is the same.

Paul Simmonds, Digital Marketing Manager of Wunda Group, says where a radiator might work with the water heated to as much as 90ºC, underfloor heating can function at temperatures as low as 35ºC.

It is a particularly beneficial method of heating when used in conjunction with heat pumps, which are likely to become increasingly common as gas boilers are phased out, just as gas boilers and central heating took over from open coal- and wood-burning fires in the 1950s and ’60s – and for the same reason, environmental legislation. The Clean Air Act of 1956 created ‘smokeless zones’ where coal and wood could not be burnt on open fires.

The legislation now is the Future Homes Standard. The government says its work on a full technical specification for the Future Homes Standard has been accelerated and it will put its proposals out for consultation in 2023. Legislation necessary to implement the proposals will be introduced in 2024 and the legislation will come into force in 2025.

By then new housing must achieve 75-80% lower carbon emissions than are permitted under the current regulations. As a step in that direction new homes built this year will be expected to have 31% lower carbon emissions as an ‘interim uplift’ under Part L of the Building Regulations.

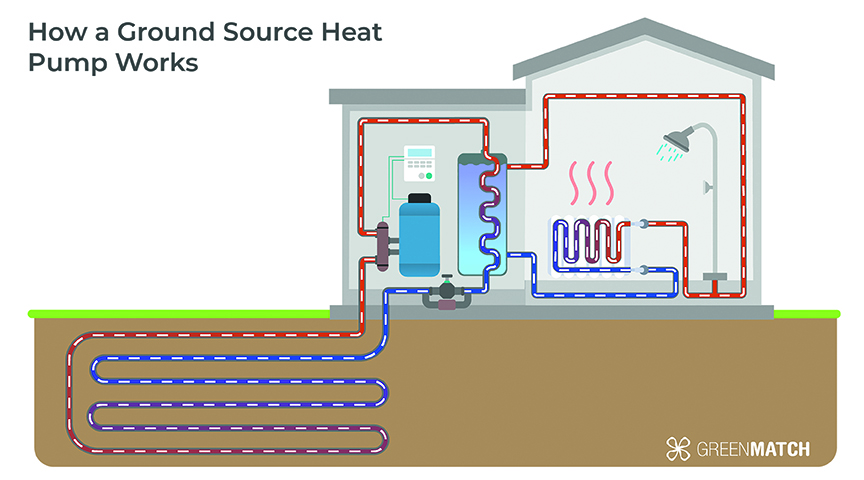

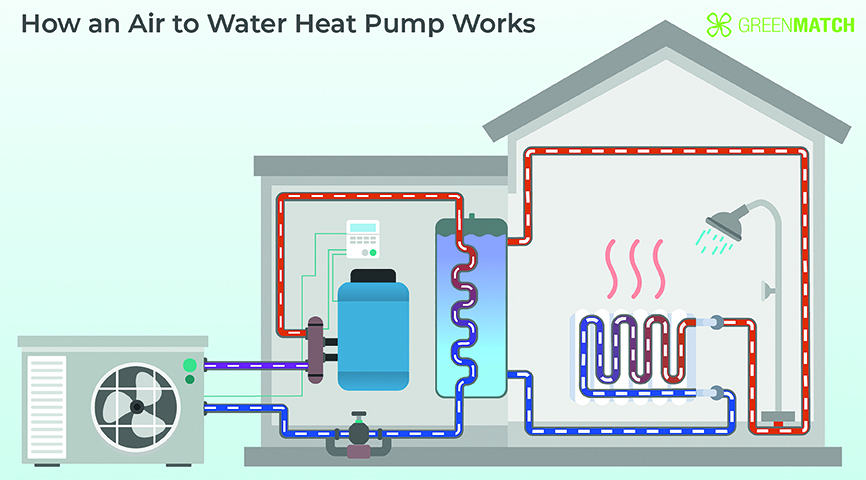

Heat pumps are expected to play their part. They work on the same principal as a fridge, only in reverse, and give as much as 3-4kW of heat from each kilowatt of electricity they use to pump water around the system.

Because of the way they work, heat pumps can be installed that can also be used for almost free cooling in hot weather, the only operating cost being an electric pump.

In January the government also opened the second stage of its two-part consultation on proposed changes to Part L (Conservation of fuel & power) and Part F (ventilation) of the Building Regulations for non-domestic buildings and existing homes (see bit.ly/netzero2).

This builds on the Future Homes Standard consultation by setting out energy and ventilation standards, as well as including proposals to mitigate against overheating in residential buildings.

It proposes a Future Buildings Standard that provides a pathway to highly efficient non-domestic buildings that are better for the environment and, like houses, will be zero carbon ready so they are fit for the future.

According to the UK Green Building Council (UKGBC), the UK’s built environment accounts for around 40% of the country’s total carbon footprint. Almost half of this is from energy used in buildings (cooking and plugged in appliances) and infrastructure (roads and railways), which have nothing to do with the functional operation of the building itself.

Heating property results in 10% of the nation’s carbon footprint and homes account for more of that than all other building types put together. Decarbonising our heat supply is a major challenge. Another is the carbon embodied in construction materials, notably concrete and steel. Annual embodied carbon in construction is currently higher than the target for the total built environment set by the government-instigated Green Construction Board (GCB) to be achieved by 2050. The GCB used to have its own website at www.greenconstructionboard.org but the board seems to have gone under cover lately.

Although there have been erratic annual variations, the carbon footprint of the built environment has reduced since 1990. Insulation installation rates between 2008 and 2012 and decarbonisation of grid electricity as renewable energy has replaced coal (in particular) have both contributed to this downward trend, although the amount of insulation being fitted started to decrease after 2012.

Generally, the newer a building is the more energy efficient it is, with zero carbon ready buildings being more efficient still.

However, 80% of the buildings we will be using in 2050 have probably already been built – about 20% of them were built before 1919 – so decarbonising existing buildings is going to play a major part in reducing the carbon footprint of the built environment.

Products such as Wunda Group’s Wundertherm will help. Wundatherm is hot water underfloor heating that is laid on top of existing floors, so they don’t have to be dug up. It comes in various versions for use with different floor coverings, including stone.

Schemes such as the Government’s £2billion Green Homes Grants could play an important part in making the existing building stock greener. The grants cover two-thirds of the cost of projects up to a maximum of £5,000 for most people (up to £10,000 for 100% of a project for those on some benefits).

Although that will not cover the cost of most heat pump installations, it helps. And heat pumps can also get the benefit of the Renewable Heating Incentive in both domestic and non-domestic buildings. The domestic Renewable Heating Incentive for a ground source heat pump, for example, pays 21.17p/kWh of energy generated by the heat pump. For an air source heat pump it is 10.85p/kWh.

Green Homes Grants have been extended to the end of March next year, purportedly in response to the Covid-19 pandemic, although to get a Green Homes Grant the work has to be carried out by an installer registered with the government’s TrustMark scheme (you can find companies near you that have signed up to it on the TrustMark’s website, www.trustmark.org.uk/find-a-tradesperson). Not many installers have signed up to it, possibly due to a reluctance to get involved in any more paperwork and bureaucracy. In order to sign up you have to belong to the Microgeneration Certification Scheme or hold Publicly Accessible Standards certification to PAS 30 or 35, depending on the kind of work you do. Because of the poor take up, the government is now allowing builders that are registered to sub-contract work to tradespeople who are not registered in order to get wider coverage.

How much a heat pump costs varies with each installation and the type of heat pump. The most popular are air source heat pumps because they are the least expensive to have installed. They look like air conditioning units on a building and account for 87% of installations in the UK, according to the GreenMatch website that helps people find energy saving solutions and tradespeople to install them.

Air source heat pumps are the least expensive option and account for 87% of installations.

Air source heat pumps are the least expensive option and account for 87% of installations.

GreenMatch says it costs the average household between £8,000 and £18,000 to have an air source heatpump installed. A ground source heat pump installation normally costs between £13,000 and £35,000.

The GreenMatch website (www.greenmatch.co.uk) contains a lot of useful information for people wanting various energy saving installations, from double glazing to solar panels, as well as heat pumps. It includes details of grants available and the Renewable Heat Incentive tariffs.

Trades installing the systems sign up to the website and GreenMatch puts those using the site to search for installers in touch with up to four companies that have signed up with it and can carry out the work. Companies pay a fee to GreenMatch for the work they get.

Below. Wunda’s Paul Simmonds says: “We developed Wundatherm to make top quality floor heating affordable to all. Simple, quick, easy to install. Any builder can install the boards, any plumber can commission the system and any electrician can fit the controls.” To read more from Wunda click here.