The art of stonemasonry : Alex Wenham

Since he returned to the UK from Paris in 2015, Alex Wenham has been fitting his stonework around the raising of his children. Now they are at school and Alex, who lives in Oxfordshire, has marked his return to full-time work by launching a new website and winning a contract to repair a statue at Magdalen College, Oxford. And the College liked his work so much they are discussing more projects with him.

Alex has famously taken top honours at the European Stone Festival three times and was only narrowly beaten into second place at this year’s event in Hungary by another Briton, Mark McDonnell.

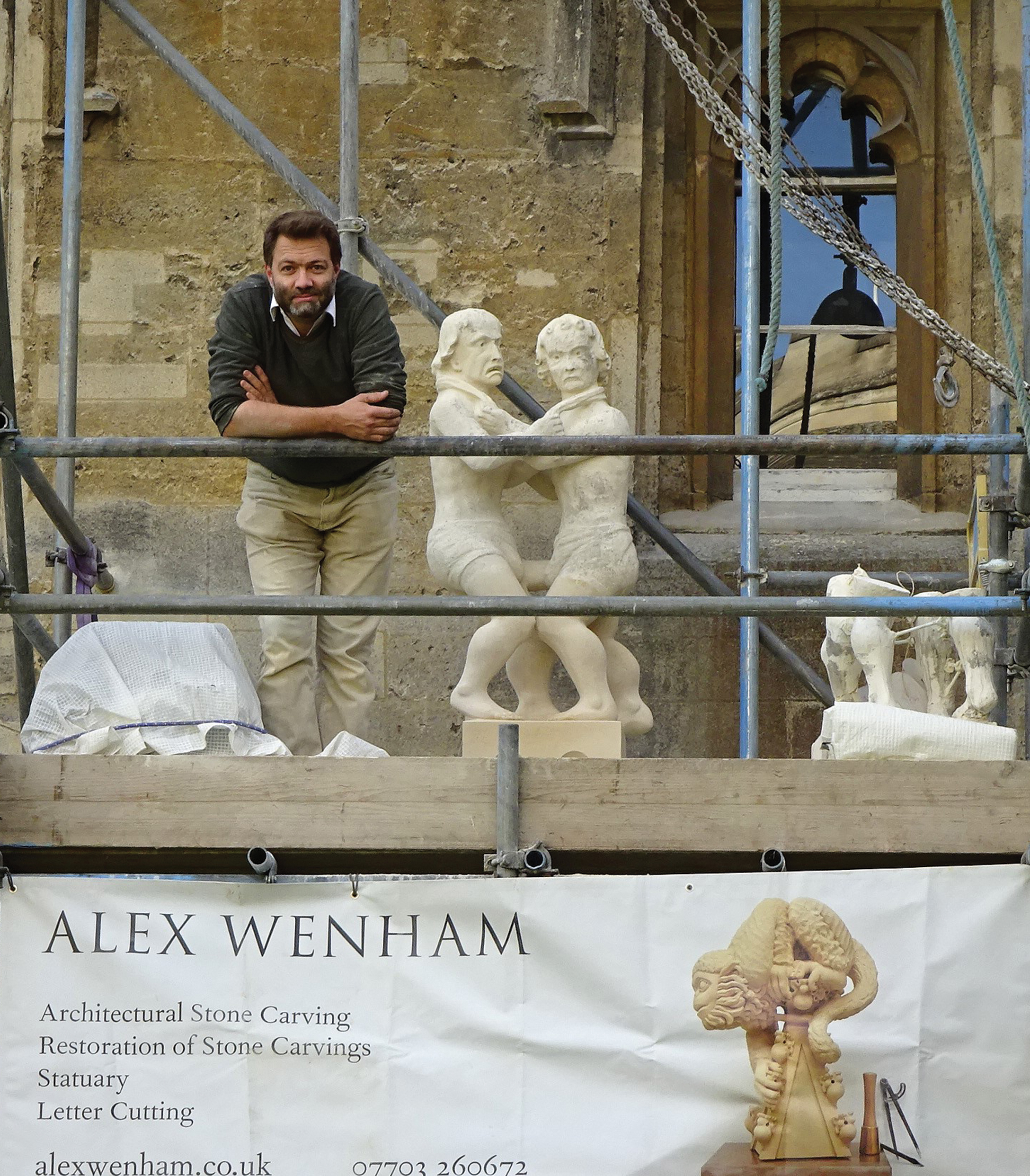

At Magdalen College, the statue he repaired was the wrestlers, which were in danger of toppling off the building. The picture on the right shows them before Alex started work on them. You can see the extent of the weathering of their legs and the plinth they are on. “What was holding them up was not much more than a sandcastle,” says Alex, who believes he was brought in only just in time to save the sculpture.

At Magdalen College, the statue he repaired was the wrestlers, which were in danger of toppling off the building. The picture on the right shows them before Alex started work on them. You can see the extent of the weathering of their legs and the plinth they are on. “What was holding them up was not much more than a sandcastle,” says Alex, who believes he was brought in only just in time to save the sculpture.

It was a one-off job and Alex was the sole contractor working on it.

The building that the sculpture is on was constructed in the early years of the 16th century – and it is possible that the heads and torsos of the wrestlers date from that time, although the legs had been replaced at least once. They were the work of Victorian masons. The stone used had not weathered as well as the older stonework above the legs.

The building that the sculpture is on was constructed in the early years of the 16th century – and it is possible that the heads and torsos of the wrestlers date from that time, although the legs had been replaced at least once. They were the work of Victorian masons. The stone used had not weathered as well as the older stonework above the legs.

The stone originally used for the construction of the building is not recorded but would probably have come from a quarry not too far away from the site of the building.

To Alex’s eyes, the stone used to carve the wrestlers looked like a Bath stone. If it is, the current statue must be a replacement of the medieval original because Bath Stone did not arrive in Oxford until the opening of the Kennett & Avon canal in 1810. On the other hand, some of the local stones used to build Oxford colleges resemble Bath Stones, so the older remaining parts of the statue could date from the time of the original build.

For restoration purposes, this building has seen Bath and Clipsham limestones used at various times.

The legs are clearly the most vulnerable part of the statue, with the weight supported on four relatively thin ankles. The fact that the legs had been replaced at least once emphasised this vulnerability. The Victorian repair had used Bath Stone and as the ‘before’ picture inset on the previous page shows, it had not weathered well and was in a worse condition than the older stonework, which has again been restored and retained.

Alex did not think the use of Bath Stone or Clipsham would be appropriate for the replacement legs and plinth required. “I felt it needed something else and we ummed and ahhed quite a lot. There were stones that were a good visual match but I didn’t think would be strong enough.”

In the end Cadeby limestone was chosen, from Doncaster. “It’s much firmer than Bath Stone,” says Alex. It was supplied by Blockstone, which operates the quarry.

Alex carved the plinth and the legs from a single block. He had dismantled the statue and taken it to his workshop to repair. The college building is listed Grade I, so everything had to be approved before work could commence in stone.

In the workshop, he separated the Victorian replacement legs and plinth from the upper part of the statue.

Some repairs were required on the older stone. The chin of the figure on the left was crumbling and was replaced by an indent. Other repairs used lime mortar and glass fibre with resin.

In order to get all the work approved before he started carving, Alex made a model in plaster of Paris to get his proposals signed off.

One foot of the sculpture was completely missing and the toes of the others had eroded, but there was enough detail to make it pretty clear what it should look like. “There wasn’t too much conjecture,” says Alex. “Although the stone had gone it had left a ‘shadow’ outline of where it had been.”

Alex left plenty of surplus stone around the legs he carved in the workshop so that he could adjust the stance of the figures as necessary on site.

Fitting it together was difficult. “It was a bit stressful,” admits Alex. “The top and the bottom are not joined in one flat plane but at four different heights. I took my time to get it all lined up and left a whole load of support material for fixing, just in case there was more weight on one leg than the others. It was so uneven; I didn’t want it to break.”

Alex started the project in mid-July and finished it in October, with two weeks holiday in between.

The wrestlers look almost as if they have dwarfism, but Alex suspects the lifesize heads and torsos supported on shortened legs are more to do with the practicalities of the structure than a depiction of dwarfism.

Statues often wear cloaks or have other drapery that reaches the ground; or they might lean on something to provide more support. These figures lack such reinforcement and longer legs would be even more vulnerable to erosion.

It has also been suggested that the foreshortening of the legs is to improve the perspective from the ground, but that probably is not the case because although the legs look less shortened from the ground, they still seem out of proportion.

The wrestlers are part of a series of 23 sculptures around the quadrangle, some of which are virtues and some sins (such as gluttony and lechery). They are all somewhat cartoonish and all in need of some degree of repair that Alex would hope to be involved in.

Next, though, Alex is through the selection process for carving a sculpture of Colin Dexter, who wrote the Inspector Morse books set against the background of the Oxford Colleges. The clients are the Inspector Morse Society and Oxford City Council.