British Normandy Memorial: The sacrifice recorded in stone at last

Stone specialist S McConnell & Sons worked with architect Liam O’Connor to produce this worthy memorial to 22,442 people who fought and died in the name of freedom.

Long overdue. That’s the most common comment in response to the official opening on 6 June of the British Normandy Memorial. It commemorates the 22,442 British personnel and those serving under British command, which includes nurses as well as soldiers, who died establishing a European mainland bridgehead that led to the defeat of the Nazi fascists and the end of World War II.

Long overdue but worth waiting for.

It was designed by architect Liam O’Connor, who says he looked at memorials built after the first world war by people like Lutyens and Baker. “But this is not a copy of those – we always invent something new. It’s a cloister garden, which you associate with ancient religious sites.”

He says if there were some sort of irreducible essence of a memorial it would be a feeling, which is why parking is kept separate, requiring a walk to reach the structure itself. On the way you might hear a church bell ringing, the rustling of trees (and a lot of trees have been planted), bird song, the smell of the sea. It is all conducive to reflection.

“It gives the impression of being in a garden structure, in a way like the Elysian Fields, although they were to forget whereas this is to remember – champs de mars, the French say.”

He says being in a garden is a light-hearted experience even though commemorating those who have died is solemn. “I have tried to reflect the balance of levity and profundity.”

Liam O’Connor, the architect: “We want people to feel a profound, elevated sense of emotion as they walk slowly towards the heart of the memorial, as it builds from the landscape towards architecture and an ever increasing sense of the prominence of the sea and that relationship between the historic battle space of the D-Day landings and the memorial.”

The £30million memorial, largely paid for by the British government with some private contributions and fund-raising, officially opened 77 years to the day after the D-Day landings in Normandy.

The sculpture of D-Day soldiers by David Williams-Ellis standing on its triangular plinth of Tarn granite.

The sculpture of D-Day soldiers by David Williams-Ellis standing on its triangular plinth of Tarn granite.

The site selected for the memorial is a field overlooking what was code-named ‘Gold Beach’ for D-Day, in the town of Ver-sur-Mer, quite close to the spot where Company Sergeant Major Stan Hollis of the 6th Green Howards won the only D-Day Victoria Cross.

‘Gold Beach’ was one of the three beaches where British and Canadian troops landed. Others were ‘Juno’ and ‘Sword’, while the Americans landed at ‘Utah’ and ‘Omaha’. The five beaches are along a 50-mile stretch of coast. The Americans and Canadians already have memorials in Normandy.

Liam O’Connor says the site originally proposed for the British Normandy Memorial was 15 miles or so further along the coast, nearer to Sword Beach. But it was too confined and the 50-acre location eventually chosen for the memorial is more suitable because it is unsullied by any form of inappropriate development.

The monument was built by the stonemasons S McConnell & Sons, based in Northern Ireland. The French main contractor on the project was Eiffage.

It had been hoped that the surviving veterans of the battle could have gone to France for the opening, but because of the Covid restrictions most instead gathered at the National Memorial Arboretum in Alrewas, Staffordshire, where they watched the opening ceremony by live satellite link. A recording of the event can be seen on the website of the Normandy Memorial Trust at www.britishnormandymemorial.org. It includes video of the construction work and interviews with Liam O’Connor and Alan McConnell, Managing Director of the stone specialists.

Dominating the National Memorial Arboretum where the veterans were gathered is another memorial, the Armed Forces Memorial, conceived and realised by the same combination of Liam O’Connor and S McConnell & Sons. Even the source of the lettering was common to both, coming from the workshop of Richard Kindersley.

It is sobering to consider that the Alrewas Armed Forces Memorial, which commemorates those killed in action since the end of World War Two, carries about 15,500 names, compared with the 22,442 on the Normandy Memorial.

The first stone being laid.

The first stone being laid.

To one side of the Normandy Memorial there is a separate but associated memorial to the French who died in the battle, both military and civilians; a memorial Alan McConnell says is an outstanding structure in its own right.

Alan says it is impossible to be unmoved by what the new British Normandy Memorial represents. He and three of his masons who had gone to France to give the memorial a final clean for the opening day were among the few British people at the unveiling. “I stood looking down on Gold Beach and thinking about the young men, some still in their teens, who fought there. Where I was standing would have been where the Nazis were firing down on them. It was something to think about; the freedom it’s given us. We should be so, so thankful.”

The memorial is constructed using Massangis limestone, quarried in France by Polycor, who Alan McConnell praises for supplying the raw blocks. “They did as much as ever they could to get the stone to us and we had a good head start on getting the stone in from early in 2019.”

Worked stone leaving McConnells' premises in Northern Ireland on its way to Normandy.

Worked stone leaving McConnells' premises in Northern Ireland on its way to Normandy.

Under other circumstances there might have been a brick or concrete core with the stone built around it, but here it was decided to build in solid stone.

Liam O’Connor says: “The memorial is a prominent recollection of one of the most important events in the 20th century. Why would you do anything but build it in solid, load-bearing stone? All the effort and skill in it is a reflection of the ideal of the memorial. It’s a very unusual space.”

About 3,700 tonnes of Massangis were delivered to S McConnell’s works in Kilkeel, Co Down, to be worked into the various elements required for the construction, which includes 160 stone columns topped with oak beams.

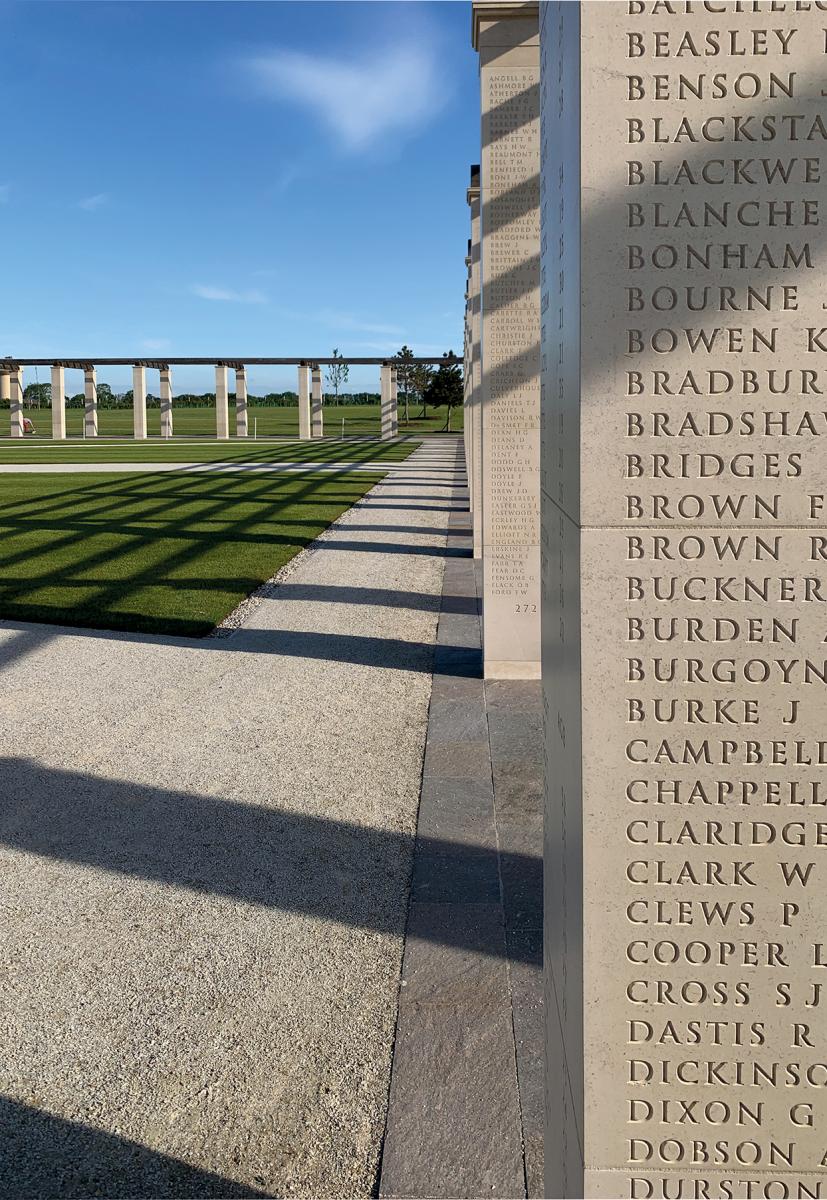

The names, in 25mm high lettering, are cut into the stone of the columns, with those who died on D-Day itself on the structure at the front of the memorial, in the centre of which is a bronze sculpture of soldiers by David Williams-Ellis.

David is a British sculptor whose father was a wartime lieutenant in the Royal Navy commanding a motor torpedo boat that supported the Normandy operation. The sculpture stands on a 25-tonne single triangular block of Tarn silver-grey granite supplied by Carrières Plo. It is the largest piece of rock in the project.

Standing are (L-R) Alan McConnell, Liam O’Connor and a representative of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

Once positioned it was drilled to take the dowels to secure the sculpture. Alan McConnell wanted to wait until it was onsite to drill it to be sure the holes were in the right place. With the plinth prepared, the statue, which weighs about eight tonnes, was lifted into place. “It was fun putting that up,” says Alan, but it was achieved without incident.

The construction work onsite started in September 2019. At the peak, McConnells had 12 people onsite, and because of the Covid restrictions they could not always return to the UK at weekends. McConnells rented houses for them to live in while the work was in progress.

Of course, this was just one of the projects McConnells was working on last year and the 12 people in France were among 60 people employed by the company as it also worked on various restoration projects in Northern Ireland and a private house newbuild in Newry.

The disruption caused by Covid to McConnells work on the British Normandy Memorial was small, though. The original finish date was September and the delays pushed that into the first week of October, but made little difference to the grass and tree planting for landscaping, which had become established in time for the opening.

The willingness of McConnells to make sure projects run on time whatever might be encountered along the way is just one of the aspects of working with the company praised by Liam O’Connor.

“They are such a great team,” says Liam. “They have a great attitude. We did look at some other companies to work with them but were struggling to find anyone that could achieve the same tolerances. They have a phenomenal work ethic. You give them something super precise and they achieve it.”

Cutting more than 22,000 names into the stonework took McConnells more than a year using their two big Omag CNCs.

Alan says: “The stone started arriving in February 2019. There are 160 columns and seven stones in each column, five of each with names on them. Every face had to be perfectly flat and every stone had to be 100% accurate.”

To make sure they were, they were ordered oversize and finished in McConnell’s workshop. “Every face was milled and then rubbed by hand,” says Alan.

The lettering was supplied by the Kindersley workshop as a digital file, which McConnells translated into a file that its CNCs could use. The names are on one face of the stone, with the ranks and ages of the person on another face.

“There was a lot of setting up. The writing had to be on the right face and in the right order and the stones identifiable onsite. So each stone had its identification and orientation cut into the top of it – we weren’t taking any chances! You can imagine the work involved in setting that up, but it had to be bullet-proof and we had to have ways of checking to make sure it couldn’t go wrong,” says Alan.

With 1,120 stones for the columns alone going to site, all required to be used in the correct position, identification was essential.

With 1,120 stones for the columns alone going to site, all required to be used in the correct position, identification was essential.

As well as all the lettering, each block had to be drilled so it could be threaded on to a stainless steel guide and positioned using stainless steel dowels.

The memorial is in an exposed, elevated position with a relentless wind making it bitterly cold in the winter, says Alan, who was a frequent visitor to the site during construction and was delighted to be able to be there for the opening. But at least the wind meant there was little chance of Covid transmission in the air.

Alan: “We left the site last October, when there was still a lot of landscaping to be carried out. Going back out this summer and seeing it in its matured state was lovely. There’s a big difference.”

Credit for the memorial should include the efforts of D-Day veteran George Batts, who was an 18-year-old Royal Engineer (Sapper) when he landed on Gold Beach on the morning of D-Day tasked with clearing mines and booby traps. He survived and eventually became the National Secretary of the Normandy Veterans Association, which has long held an ambition to see a defining British monument built on a single site in France to commemorate the men and women of the British Armed forces and civilian services who lost their lives in that Normandy Campaign.

The Normandy Memorial Trust harnessed George’s long-held passion and, with HRH The Prince of Wales (Prince Charles) as Royal Patron and Lord Ricketts as Chairman, along with many other venerable and high profile trustees, such as broadcaster Nicholas Witchell, secured a commitment from the UK Government to construct the powerful and inspiring statement in Normandy to honour the fallen.

Nicholas Witchell fronted the National Memorial Arboretum part of the opening of the memorial on 6 June, as you can see on the recording of the event, and Prince Charles spoke on a video link. He had hoped to attend the opening in France but, with the veterans unable to attend, neither did he.

The Mayor and residents of Ver-sur-Mer should also be recognised for their contribution to the memorial. The Mayor gathered the land owners together and impressed upon them the significance of the memorial and the benefits of it putting the town firmly on the tourist trail.

If you draw a line on a map of places to visit along the coast, the British Normandy Memorial is on that line between the Canadian and the American memorials and will inevitably attract people to Ver-sur-Mer.

Liam O’Connor has also designed a visitor centre for the site, but that is part of a second phase of work.

Below: The memorial to the French people who died in the Battle of Normandy. It is a separate part of the British Normandy Memorial that Alan McConnell describes as an outstanding structure in its own right.