Gallery : Michael Scheuermann

Between commissions, stonemason and sculptor Michael Scheuermann has been back to school this year, working with youngsters at schools near his Eastside Studio in Birmingham. He says it was not only the children who learnt something.

How do you represent a child’s drawing in coloured crayons as a sculpture in stone? That is one of the challenges that faced Michael Scheuermann, a stonemason and sculptor, this year as he introduced the art and craft of working stone at primary schools in the Midlands.

“You have to find ways to do it because the children have to claim ownership of the finished work. Otherwise I might just as well carve something of my own design for the schools,” says Michael.

Michael has now been involved in several schools projects. One of them, at his own six-year-old daughter Anya’s school, involved introducing the five to 11-year-olds to stone and the tools to work them.

He explained to the children about what he wears when he carries out the work – the safety glasses, the ear defenders, the protective clothing – and how he cuts and shapes the stone. He presented a slide show of how stone is won from the ground and how it came to be formed in the first place over millions of years. The pictures of a volcano are always popular.

“Of course, you have to talk differently to the six-year-olds than you do to the year six children,” he says. He carves a piece of stone while the children watch, “so they know it’s real”.

He says: “After a day at school I’m whacked. Give me a piece of stone to work anytime. There’s a completely different energy involved in teaching.”

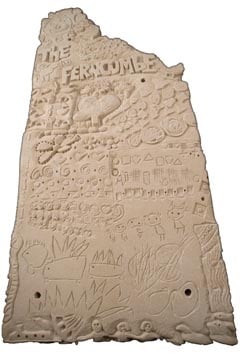

The children are encouraged to produce drawings for Michael to carve into the stone and Michael chooses one from each class to include in his work. At the school his daughter attends – The Ferncumbe in Hatton, near Warwick – he carved the designs on to a piece of Coombefield Whitbed Portland limestone 1.6m x 800mm, starting at the bottom with the work of the youngest children and moving up to the oldest at the top.

The project was one of eight organised by Sharon Hall, an Extended Services Cluster Co-ordinator in south-west Warwickshire, for the seven primary schools and one secondary schools in her cluster.

Each school had £3,450 from the government and Arts in Warwickshire to spend on a project to create an artwork in their school. The head teacher at the Ferncumbe had seen some of Michael’s work and the school chose him as their artist in residence for their project.

Sharon Hall said of The Ferncumbe project afterwards: “I think the children are really proud of it. It’s there now for time immemorial.”

At another of the schools where Michael has taught – Brandhall in Birmingham – he produced a smaller, child-size Bath stone version of a stone sofa he and his colleagues had carved as part of the Rugby Writers commission that was featured in this magazine in January.

At Honeybourne First School near Evesham, working with landscaper Anthony Ashbee, Michael created a circular feature with three paths coming off it in a dark Indian limestone and granite. And at Roman Way First School near Redditch he worked with John Cutts Landscaping on a project that incorporates sculptures carved from three large blocks of Peak Moor sandstone.

Michael has taught as well as carrying out his commissions for several years. He started at the Midlands Art Centre in Birmingham, before it closed down two years ago. He now runs classes at his own Eastside Studio workshop in Birmingham as well as now having started introducing the craft to schools.

He enjoys being involved in education, but his main work remains his commissions. He particularly likes contrasts and surprises in his work, such as the appearance of softness in the chesterfields and chaise longe in Wattscliffe sandstone for the Rugby Writers project. The furniture emerges from the raw stone left at the back of the seats. “There’s a massive tension there,” says Michael.

It is a theme he is currently developing, adding even more contrast in pieces he is preparing to exhibit at Chelsea Flower Show in the spring. He likes the idea of bringing the viewer back to the raw material from which the work is created because people tend to take artifacts for granted, forgetting that somebody had to transform materials into that finished product.

It is a theme that goes back a long way with Michael Scheuermann, who, as his name suggests, comes from Germany.

It was in Germany that he served his apprentice as a stonemason and carver, completing his training in 1991. He took up stonemasonry, he says, because he wanted to do something with his hands. He explored other crafts, but settled on stone because he found the medium particularly rewarding.

Like a lot of young masons, once he had finished his apprenticeship he went off to see the world. In China he met an English jewellry designer, Alison, who is now his wife and a critical collaborator in his work.

They returned to the UK where Michael was able to expand his horizons with a fine art degree at the University of Wolverhampton and a Masters at the University of Central England (now Birmingham City University).

He continued to use stone but wanted to explore different aspects of it. His final exhibition piece for his Masters, in which he gained a distinction, involved hanging up on steel supports pieces of Portland limestone, fired at 1,000ºC to turn it into Calcium oxide (quicklime), which deteriorates quickly. As the stone crumbled the residue was collected on glass trays below the stones.

“It was about now,” says Michael. “Not a position of permanence but impermanence, which we are not often aware of. We’re not really about now. We think about the future and the past. All the time we play through scenarios that never actually happen. It’s a waste of time and energy. And while I’m thinking about the past or the future I’m not in the present.”

He did not record the piece by taking photographs or filming it because the whole point of its accelerated decay was its ephemerality, bringing into the realm of human timespan that which normally occurs in geological time.

Even in the more day-to-day work of a stonemason / carver, philosophy permeates Michael Scheuermann’s work. The pictures on the left of this page show some of the work he carried out to restore a Portland limestone war memorial in Solihull.

He does not normally like working on war memorials because he feels they glorify the weapons that have led to the deaths they have been built to commemorate. But the memorial in Solihull was different. The carvings on the stone were more about remembering the people.

“A nurse was standing next to an empty bed. Was it empty because the person had died or because they had recovered? Above the bed was a plaque with a name on it, but we left it blank on purpose.

“I found it was really exciting. First of all there was the irony of a German working on a war memorial in England. I carved it in situ and people would come up and talk to me and wouldn’t mention the war. One guy had been a pilot in the war. Another had looked after prisoners of war. It was really interesting.”

Among the carvings Michael worked on were panels about 750mm x 450mm. They had been carved in the 1920s and referred to the First World War but had become weathered so that detail was missing. The Rotary Club in Solihull commissioned Michael to re-carve that detail into the existing Portland stone.

Michael: “The idea was to bring them back to life. I had to read the traces of carving that were left there. I worked with a guy from the Rotary Club who had been in the army. He explained to me what I needed to know to be able to interpret what was there – how their boots were tied up, things like that. I had to refer to books as well to find out what gas masks looked like and ammunition boxes. The nurse’s hat didn’t make sense, but I found the answer on the internet. She was a student nurse. Things like that came out of it.”

Armed with the results of his research, it started to become straight forward to read the work of the original carver.

Michael intended to be as faithful as possible to the intentions of the earlier work, although he has made some alterations – for example carving a face on the airman where previously there had been a flying mask.

“There were only a few areas where I had to say this will look like this now.”

The philosophy which pervades his work, giving meaning to the form and even the process involved in creating it, is important to Michael. His critical analysis means he is learning all the time. Even when he is teaching.