Dr Kristian Steele, Darren Anderson and Richard Hunt from Arup, the consultants and technical specialists in design, planning and engineering, discuss what needs to be considered when looking for environmentally friendly stone.

Sustainability. It is a subject that has risen in importance significantly over the past 20 years. It represents a complex challenge that, if we are to meet, will require holistic thinking bringing together multiple dimensions, many of which are not traditionally addressed in the design process.

The built environment, with its vast consumption of energy and resources and resultant emissions, has an important part to play. This is well recognised, and the drive is now on to design, construct and manage our society in such a way to ensure its impacts are minimised while maintaining quality infrastructure.

It follows that the extraction, manufacture, and supply of building materials must be considered carefully within this context. The problem is that material suppliers and designers often only view this subject from a few, narrow perspectives. What is the product recycled content? Is it natural? How far has it travelled? And what is the carbon footprint? These are some of the questions commonly asked.

The truth is the debate is more complex, and must be assessed across multiple criteria and in full life cycle terms.

Crucially, consideration must also be made of the benefits a material has, as well as its burdens. In this way a balanced and holistic decision can be made ensuring the design is technically fit for purpose, as well as having a minimum impact on the environment and society.

To remain competitive, the stone industry should take note and respond accordingly.

It must ensure its materials are responsibly supplied as defined in the standards produced by BSI and BRE. This will mean the social and environmental impacts of workings are managed, along with health and safety standards, and quality and product control.

If specified and used in the right way, stone can represent a low embodied impact solution as measured by life cycle assessment (LCA) methodologies such as the BRE’s Green Guide to Specification. Here aspects such as impact on climate change or embodied water, among others, may be measured.

But other issues such as resource efficiency are also important. This means considering mineral depletion and cutting down on waste, as well as promoting the re-use and recycling of materials through the supply chain and at end of life.

These issues represent a new agenda for the industry, and one which the majority of stone suppliers are not yet ready to substantiate the performance of their materials against.

The technical performance of stone remains important and will always form a part of the selection and approval process. But as the case study example below illustrates, Arup will look at a wide range of issues in the design and specification choices that it makes.

Indeed, technical performance along with other considerations such as aesthetics, cultural significance and the social and environmental criteria noted above need to be fully satisfied to ensure that the right material is chosen for the job.

Case study

Forest Pennant and Caithness keep Swindon green

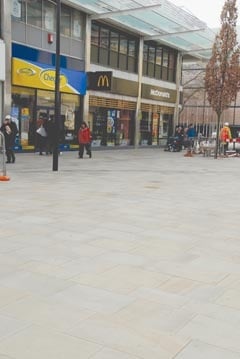

Arup were appointed as lead designers, with sub consultants Nicholas Pearson Associates, to the New Swindon Company Framework to advise on improvements to the public realm in the central shopping area of Swindon. The client’s brief was to create a high quality and durable pavement surface, incorporating artistic features and pavement art, over an area of about 10,000m2.

The South West Regional Development Agency are part funders and require all of their projects to achieve an ‘Excellent’ rating under the Civil Engineering Environmental Quality Assessment Awards scheme (CEEQUAL).

Various natural stone materials were considered, and Arup calculated scores for the CEEQUAL Energy & Carbon chapter based on whole life energy and carbon cost of materials using the Environment Agency’s Carbon Calculator to determine the carbon footprint for each material proposed.

Paving materials from a variety of UK and EU sources were considered. Clearly local stones featured prominently due to the reduced transport costs. Royal Forest Pennant stone produced by Forest of Dean Stone Firms was finally chosen based on its quality, appearance and low carbon footprint. The Forest Pennant quarry also had strong ISO 14001 credentials and environmental ethics – including developing small scale hydropower to serve the works.

Where feature stone was only available from a specific quarry – eg Caithness Stone from Scotland – we compared rail, road and water delivery to agree a method that minimised transport emissions.

Increasing focus on carbon footprint and life cycle of materials means that selection of stone suppliers by specifiers will increasingly be based on supplier awareness of these issues and the ability to provide robust lifecycle data that contributes to the assessment process and provides strong positive credentials.