The government has set a target of at least 600,000 heat pump installations a year by 2028. Heat pumps work best with underfloor heating and underfloor heating works best in association with the thermal mass of natural stone tiles. Could this be the start of a new stone sector specialisation?

It is vital that the Government should meet its target to deliver a minimum of 600,000 heat pumps a year by 2028 or there will be a great risk it will fall off course in delivering Net Zero by 2050.

So said the Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) Select Committee of MPs in its seventh report on decarbonising homes, published in January this year.

It complained that the Government has not outlined in its delayed Heat & Buildings Strategy its plans for how it will meet its heat pump target or what contingencies are in place if the target is missed.

In the Heat & Buildings Strategy the government has introduced a grant of £5,000 for householders and landlords towards the cost of installing air source heat pumps (£6,000 for ground source heat pumps) to replace gas boilers in existing properties in England and Wales starting from April.

The grant is not available for new builds, but gas boilers are banned in new builds from 2025 (which the BEIS Select Committee wants brought forward to next year) and builders will have to include heat pumps, or some other low carbon alternative to gas boilers, in new properties in order to make them carbon neutral ready. Many are already including heat pumps in order to make properties easier to sell.

It might not be pretty but it could help save the planet.

Boosting demand

The grants to help with retro-fitting heat pumps in existing properties come with a budget of £450million over three years. So that’s a maximum of 90,000 properties that can benefit, while the Office for National Statistics says there are 27.8million households in the UK, 85% of which use gas boilers for heating and hot water.

The grants will be distributed to the companies that install heat pumps. They will apply for the grant on behalf of their customer and the grant will be discounted from the total price the homeowner pays.

If you can see a potential problem with that you are not alone. Government subsidies often simply increase the price of the goods being subsidised, even if for no other reason than demand increases. And the government does intend the grants for heat pumps should boost demand for them.

However, with air-source heat pumps (which are the cheapest kind available and what the vast majority of people choose) typically costing £10,000 to £20,000 for most homes, and ground source heat pump installations at between £13,000 and £35,000, critics say the grants will be an inadequate incentive for most people.

The result will be that the money will go only to those who could have afforded them without the incentive, perhaps particularly private landlords (the grants are not available for social housing).

Some argue that more efficient, larger scale underground heatpump systems covering all the houses in a development, for example, should be the longer term aim.

They would have to be maintained by an energy supplier who would charge the householders a fee, in the same way as gas suppliers do now, which creates a market solution and spreads the cost of energy supply over an individual householder’s lifetime in a familiar fashion.

The government has stressed that households will not be forced to remove existing gas heating systems, although they will be unable to replace them with the same systems when the sale of gas boilers is banned all together –whenever that might be.

No more boilers?

The independent Climate Change Committee (CCC), a statutory body established under the Climate Change Act 2008 to advise the government, says it should be no later than 2033. The government has said it will introduce a ban in 2035, but there has been a lot of opposition to that and it looks as if the date might be put back to 2040.

Such vacillation does nothing to encourage householders to get on and make the change. Some even express doubts that a change will ever be necessary as hydrogen could be used to burn in boilers, at first as a mix with natural gas to reduce CO2 emissions and eventually just pure hydrogen.

If hydrogen could be economically split from water, burning it in a boiler would simply turn it back into water. The technology already exists, although a step change in hydrogen production would be required to make it viable to supply through the mains. Nevertheless, some think it makes installing a heat pump look like a white elephant – although rapidly rising gas prices might prove to be an incentive to install heat pumps for those who can afford them.

Many in the construction industry say a concise roadmap to phase out the sale of gas boilers by 2035 would have been much more effective than a limited number of £5,000 (or £6,000) grants, especially if such a roadmap was accompanied by significant funding, such as the £2billion allocated to the failed Green Homes Grant before it was withdrawn with 95% of it unclaimed.

The BEIS Select Committee seems to agree. In its seventh report it opined: “The Government should work with industry, consumers, and affected workers to produce an effective road map detailing how the transition to low carbon heating will take place, and to include what this will mean for different households in different parts of the country and for workers whose jobs might be affected in existing carbon intensive parts of the heating sector. We recommend this is done at local level in partnership with local government. The long overdue Heat & Buildings Strategy published in October 2021 failed to provide sufficient policy detail or clarity on delivery.”

So far, the installation of heat pumps, nearly all of them air source versions, has been limited. In 2019, 34,896 hydronic heat pumps (which transfer heat using circulating water in the same way as a gas boiler heats water circulating in radiators) were sold in the UK. That number includes hybrids, which include an alternative heating source such as a gas boiler, because heat pumps are not usually capable of providing both heat and hot water at the same time, so an alternative system is used to provide hot water from the taps.

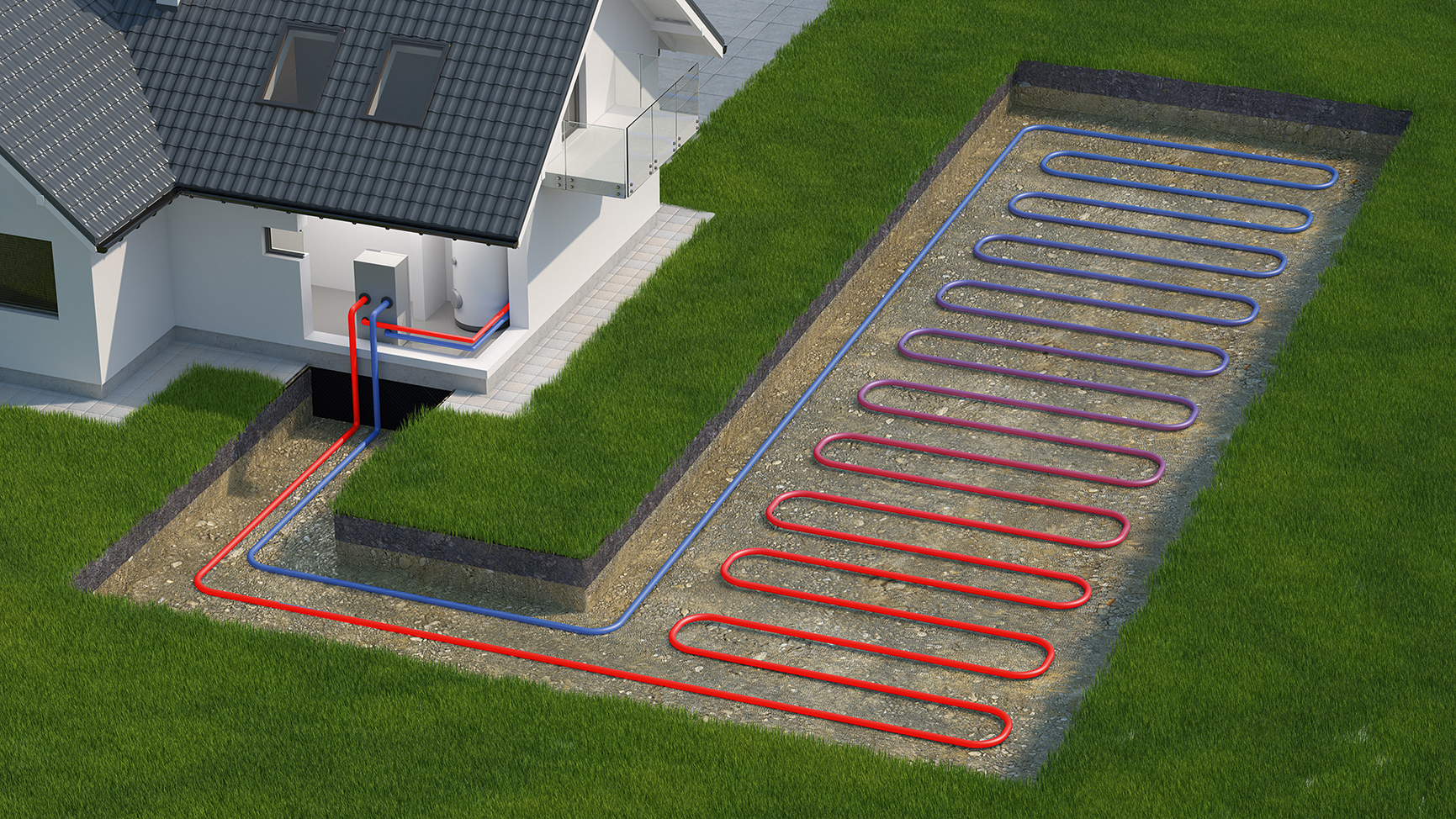

There are £6,000 grants available to help pay for the installation of ground source heat pumps, which typically cost between £13,000 and £35,000.

Not enough installations

In its 2021 Progress Report to Parliament, the CCC stated that “despite a small improvement in the rates of heat pump installation, these remain far below the levels that are necessary”.

It noted that annual heat pump installations in homes had risen marginally to 36,000 in 2020, driven mainly by an increase in retrofit installations of just under 23,000.

It is also starting to become clear that retrofitted heat pumps are not living up to householders’ expectations of their heating, and some of those who have had heat pumps installed, who tend to be at the wealthier end of income brackets, are also subsequently having new gas boilers installed to keep their homes cosy.

One of the problems is that heat pumps are being installed to work with existing central heating systems that have wall-mounted radiators. A gas boiler would be expected to heat those radiators to 70-80ºC in order to keep a room at a comfortable 21ºC. Heat pumps deliver water to the radiators normally at no more than 40-50ºC. That’s the sort of water temperature range most people would shower in.

To produce water temperatures of 50°C, the Coefficient of Performance (COP) of a heat pump is approximately three (so for every one unit of electricity used to power the heat pump, it produces three units of heat). As radiators are typically sized for a flow temperature of 71–82ºC, those in most houses would be undersized for use with heatpumps.

To achieve the same level of heating as a gas boiler achieves in existing properties will normally mean improving insulation and increasing the size of radiators or replacing the radiators with underfloor heating or, in smaller properties, air-to-air blowers.

Most people installing heat pumps do not make sufficient provision for increasing insulation and do not replace the radiators. They would not, in many cases, want to increase the wall area taken up by the radiators or the thickness of them in order to achieve the levels of heating they enjoyed with a gas boiler.

Consequently, they find the heating inadequate, leading to the subsequent installation of another source of heating, usually a gas boiler. Not ideal when the aim is to reduce CO2 missions.

Householders who have had heat pumps installed and found them inadequate also tend to talk about it. Word quickly spreads, which is not good news for the government’s 600,000 unit-a-year target for 2028.

The issues of insulation, radiator size, and alternatives such as underfloor heating are not often subjects raised by companies installing heat pumps. They tend to want to install the unit as quickly as possible and get on to the next job. Some even disingenuously advise against having underfloor heating for no other reason than they don’t want to get involved with installing it, they don’t know how to do it, and/or they don’t want to frighten the customer with the extra cost involved.

Ireland commits €8billion

In Ireland, the government announced in February its plans to provide funding of €8billion that is intended to pay for energy upgrades to 500,000 homes by 2030. Heat pumps will play their part.

The commitment is spread over eight years in order to give companies involved in the sector the confidence to invest, expand and create more high quality jobs without fearing that the bottom will suddenly fall out of the energy upgrade market.

Speaking at the launch of what is called the National Home Energy Upgrade Scheme, Taoiseach Micheál Martin said: “Today, the government is committing to support people in making their homes warmer and less expensive to heat, while also tackling our climate change crisis.

“The Irish people responded collectively, and with a sense of purpose, to the pandemic by helping protect the most vulnerable in our society. The climate crisis is just as critical for our children and future generations, as well as people at risk of fuel poverty now.

“This government’s commitment to reaching our climate ambitions is clear, and today is another step along that journey.”

Ireland has already seen the benefits of the multiplier effect of injections of investment in infrastructure from its membership of the European Union and it believes €8billion now will achieve a similar significant multiplier effect, supporting the development of associated supply chains and a transition to a carbon neutral society without anybody being left out in the cold.

Key measures in the Home Energy Upgrade Scheme include grants of up to 50% of the cost of a typical ‘deep retrofit’ for most people, but also free upgrades for those at risk of energy poverty.

There are grants of 80% of the cost of attic and cavity wall insulation to reduce, as a matter of urgency, the country’s energy use – part of the government’s response to the latest shock of rising energy prices.

The Home Energy Upgrade Scheme is also offering a start-to-finish project management service, including access to financing.

Carbon tax funding

The schemes is being administered by the Sustainable Energy Authority of Ireland (SEAI). The increased grant supports and the significant ramping up of free energy upgrades for those at risk of energy poverty is supported by ring-fenced funding from the carbon tax.

This year, €267million has been allocated for SEAI residential and community schemes. This will support about 27,000 home energy upgrades, taking some 8,600 homes (twice as many as last year) up to a Building Energy Rating of B2 (which can involve photovoltaic [solar] panels and heat pumps). B2 is generally considered the benchmark for an excellent performance in a home built before 2006. The budget will also facilitate 4,800 free energy upgrades for those at risk of energy poverty.

A radiant underfloor heating hydronic manifold with flexible tubing mounted on insulation boards. Insulation underneath the pipes is essential on ground floors or you will lose a lot of heat to the ground below.