Readers projects : Szerelmey Conservation

Szerelmey Conservation, set up by Andrew Bonner in partnership with the Szerelmey Group in 2014, is making its mark in the heritage sector with landmark projects.

The past year has been busy for Szerelmey Conservation with some landmark projects, including those featured here.

The pictures here show new cloisters, known as the Royal Artillery Memorial, built by Szerelmey Conservation at the Royal Regiment of Artillery’s garrison church of St Alban the Martyr at Larkhill on Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire.

The pictures here show new cloisters, known as the Royal Artillery Memorial, built by Szerelmey Conservation at the Royal Regiment of Artillery’s garrison church of St Alban the Martyr at Larkhill on Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire.

Below are pictures of the church of St Mary in Castro at Dover Castle following essential masonry and repairs to the flint and Bath stone walls. It is one of more than 400 properties and sites owned by English Heritage and was the first of the now independent charity’s buildings Szerelmey Conservation had worked on.

It has already led on to more work for English Heritage by Szerelmey Conservation. The company is currently working at the English Heritage sites of Hurst Castle, in Hampshire, built by Henry VIII as one of the most advanced artillery fortresses in England, and at the Royal Citadel in Plymouth.

The Royal Artillery Memorial at Larkhill pictured here has a chapel at one end with an open-sided cloister coming off it and a gate at the far end. It was completely new build on a raft of concrete for the foundations that Army engineers installed before Szerelmey Conservation arrived on site. The build comprised largely of traditional methods ideally suited to a conservation company.

The Royal Artillery Memorial at Larkhill pictured here has a chapel at one end with an open-sided cloister coming off it and a gate at the far end. It was completely new build on a raft of concrete for the foundations that Army engineers installed before Szerelmey Conservation arrived on site. The build comprised largely of traditional methods ideally suited to a conservation company.

In fact, the design, by John Simpson Architects, is based on a cloister at Woolwich, the headquarters of the Royal Artillery, which was damaged by bombing in World War Two.

In fact, the design, by John Simpson Architects, is based on a cloister at Woolwich, the headquarters of the Royal Artillery, which was damaged by bombing in World War Two.

It had housed plaques dating back to the 18th century recording significant people and events in the Regiment’s history. Some of the plaques have been put into the new memorial while others are currently being restored. They have been in storage since the war but the Regiment has decided to put them back into the new memorial as it marked it tercentenary last year.

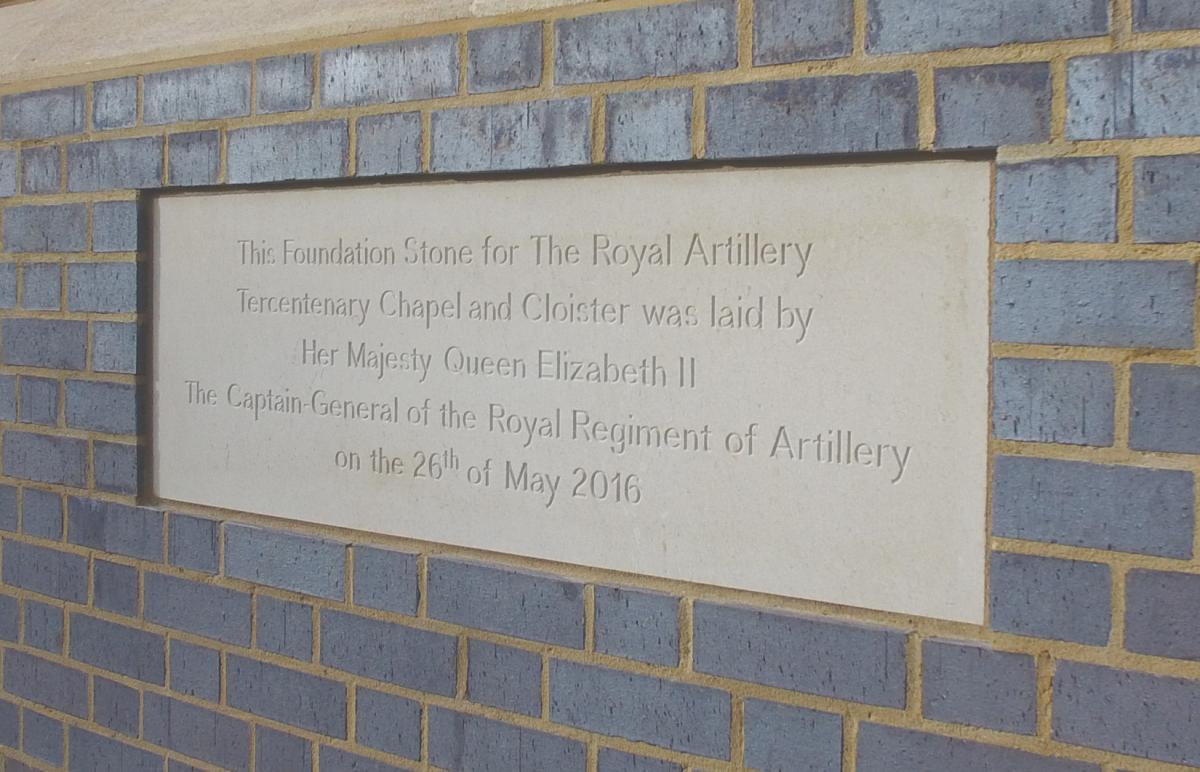

During the build (in May), The Queen, who is the Captain-General of the Regiment, visited to mark the tercentenary. Belatedly, the Regiment decided the visit should be recorded and, with two weeks to go, asked Andrew Bonner, managing the project for Szerelmey Conservation, to incorporate an inscribed stone plaque into the wall for The Queen to unveil.

Szerelmey Conservation consists of 10 people. It was established in 2014 by conservators formerly at CWO in Chichester. It still has its offices at the former CWO premises that are now the home of masonry company Chichester Stoneworks. Andrew Bonner asked his colleagues at Chichester Stoneworks, which was already producing the Clipsham limestone from Bullywell’s for the memorial, if they could produce the plaque, which they did from Portland limestone already in stock for another Szerelmey Conservation project.

Although much of the solid brick and stone construction of the memorial is traditional, it is not entirely that way.

The completion day was critical for the tercentenary of the Regiment’s annual celebrations on 4 December and to help achieve the deadline, gauged arches are precast concrete with brick slips, manufactured offsite and craned into position on top of Clipsham columns.

Although there are only 10 people at Szerelmey Conservation, the company also draws on in-house heritage skills from the wider Szerelmey Group and employs external skills as needed.

On the Royal Artillery Memorial there were as many as 12 people at a time

on-site, including carpenters and leadworkers for the roof, while Future Stone in Bristol provided the bricklayers and stone fixers.

The principal contractor on the project was Aspire Defence, which works closely with the Ministry of Defence on a number of projects.

The second project featured here is the church of St Mary in Castro at Dover Castle, constructed of flint and Bath stone. The project involved the provision of independent access scaffold to the tower, chancel and transept while essential masonry repairs were carried out to a programme of work determined by architect Carden & Godfrey.

Here, Szerelmey Conservation was the principal contractor for English Heritage.

The church goes back a long way. The tower at the west end is a Roman lighthouse, which was incorporated as a bell tower when the Saxons built the church. The church has been heavily rebuilt and restored since then and still serves the local population and the Army garrison in Dover.

Where the architectural limestone needed replacing, Stoke Ground Bath stone from Bath Stone Group was used.

The project included some significant stone conservation to the south string course with carefully indented new stonework to the tower’s brick parapet. There were some minor brick replacements using new hand-made bricks from Robus Ceramics. The flint walling was repaired using locally reclaimed materials. The work also included the replacement of lightening conductors to meet current standards.

A large part of the job involved repointing. Almost inevitably with a building of this age there had been previous cementitious repointing work that had to be removed. It was replaced with hot lime mortars.

Hot lime has become increasingly popular in the conservation and heritage fields in recent years, with its advocates claiming significant benefits over natural hydraulic lime and earlier 19th century hard cements. (For an introduction to hot lime see bit.ly/hot_lime).

Advocates of hot lime say hydraulic lime can become as hard as Ordinary Portland Cement, with the same result of accelerating the decay of old masonry. They say mortars should be considered sacrificial and should always be softer than masonry so that it is the mortar that fails rather than the masonry.

To get a better understanding of hot lime, both Robin Jarvis, who was the Szerelmey Conservation manager at St Mary in Castro, and all his colleagues at Szerelmey Conservation have attended a course to understand more about it at Weymouth College in Andrew Bonner’s home town of Dorchester, Dorset.

Robin Jarvis says: “It was the first time we had used hot lime. It makes a nice fat mortar; it’s more workable. In time I think it will come back into greater use on heritage projects.”

There were some challenges, however, as it was necessary to revisit it and keep it damp to prevent accelerated drying out and cracking. Natural hydraulic lime needs wetting and tending less often, but considering the claimed benefits of hot lime, Robin Jarvis was sold on it.

A particularly old stone was discovered in the jamb of the door on the north transept. It could well have been a stone originally used by the Romans and re-used in subsequent rebuilds. It was clearly essential to retain it, so the stone was micropinned to preserve it in situ.

The presence of old ironwork is a common occurrence in historic stone structures, commonly having been added after the original build to correct movement. There was some evidence of this at Dover. Some metal was removed, although in general it was simply treated with Fertan rust treatment where it was exposed.

Lime washing and decoration repairs, vegetation removal, repairs to clay-tiled roof and lead flashing and gutters, and repairs to internal wall mosaics completed Szerelmey Conservation’s 20-week introduction to working with English Heritage.

“It was a rewarding job,” says Robin.

The picture above shows the completed project at the Church of St Mary in Castro at Dover Castle, where Szerelmey Conservation carried out flint, Bath stone and brick repairs to the walls. It was the first time the company had used hot lime and it contracted Nigel Copsey of the

The picture above shows the completed project at the Church of St Mary in Castro at Dover Castle, where Szerelmey Conservation carried out flint, Bath stone and brick repairs to the walls. It was the first time the company had used hot lime and it contracted Nigel Copsey of the