Report: Conservation & Cleaning

Federation works to protect stone’s vital position in the built heritage

Historic buildings make a major contribution to tourism, which, in turn, makes a significant contribution to the economy. And what tourists love to visit often owes much of its attraction to the work of past and present stonemasons.

Stonemasonry has always made a significant contribution to the conservation of the built heritage of the UK and Ireland (and, of course, all over the world). But for stonemasons it was just part of the job, requiring essentially the same skills as for new build.

As Lewis Proudfoot, Stone Section Manager of leading heritage specialist Cliveden Conservation says: “The stonemason still plays a crucial role when it comes to the conservation and restoration of heritage buildings. In fact, this was a key talking point at the International Building Limes Conference, hosted by Nidaros Cathedral in Trondheim.” (There will be more from Lewis about that Conference in a future edition of this magazine).

He says there is a need to return to a more engaged way of working, influenced by analysis and understanding and led by the stonemason as the expert in this field.

Stone Federation Great Britain has re-stated stonemasonry’s claim on the heritage sector. As part of its restructuring into groups representing the various interests within stonemasonry, last year it launched its Stone Heritage Group, chaired by Bernard Burns of major specialist contractor Szerelmey. That group this year published its Stone Heritage Register, a directory of Stone Federation members offering their specialist services to the heritage sector.

The register was launched at the Royal College of Surgeons in London in May, with the help of Loyd Grossman, the celebrity Chairman of the Heritage Alliance, which Stone Federation has joined.

Bernard Burns said at the launch that Stone Federation had joined the Alliance because “we are very conscious and aware we are part of a larger team – we want to make sure we’re not a weaker link”.

Heritage Alliance is England’s largest coalition of heritage interests, bringing together independent heritage organisations such as the National Trust, English Heritage, the Canal & River Trust and the Historic Houses Association with bodies representing visitors, owners, volunteers, funders, educationalists and professional practitioners, which now includes Stone Federation Great Britain.

Combined, the organisations of the Heritage Alliance involve 6.3million volunteers, trustees, members and staff, which gives it a voice that ought to be loud enough to be heard.

One of the latest moves by the Alliance is to send a paper it has written on protecting the rural historic environment during and after Brexit to Professor Dieter Helm, chair of the Natural Capital Committee set up by the Government to report to the Economic Affairs Committee of the Cabinet, which is chaired by the Chancellor of the Exchequer. The Committee’s main role is to advise the government on how to develop its 25 year plan to improve the environment.

At the launch of the Stone Federation’s Heritage Register, Loyd Grossman said 1913 to 2013 was seen as the golden age of conservation, with a great deal of state intervention that is now coming to an end.

But, said Loyd, it was not the state that led the conservation movement but individuals such as Octavia Hilton, a founder of the National Trust (which is a charity) and William Morris, a founder of the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB), which is also a charity.

The increasing withdrawal of the state from the sector raises the significance of individual philanthropy, said Loyd.

The rolling back of the state includes the privatisation of English Heritage, that was split into two entities in 2015. The part that looks after the 400 or so English Heritage sites is still called English Heritage. The part that advises the heritage sector and reports on it to the government and is still responsible for listing buildings, is now called Historic England. And it has been active, listing another 1,184 sites in the year to August. Most of the new listings are war memorials and other wartime buildings (such as pillboxes), which have had a high profile as the country commemorates the centenary of World War I.

Historic England has published a lot of useful advice on the conservation and cleaning of war memorials online at historicengland.org.uk/advice/technical-advice/war-memorials/.

English Heritage is now a charity that has been tasked with becoming completely self-sufficient (in other words it will get no more government money) by 2023.

But to help it on its way, it has been given £80million by the government to upgrade its sites in order to make them more attractive to visitors.

It is spending that money introducing new facilities and cafes, and better historical interpretation at its sites. In Yorkshire, for example, it has carried out a £1.8million redevelopment of Rievaulx Abbey that has resulted in a significant increase in visitors rating the site as ‘excellent’ in its 2016 Visitor Survey. At Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, the addition of a creative outdoor interpretation scheme increased by 29,000 the number of visitors last year.

Historic England, meanwhile, continues to be funded by the state. An initiative from Historic England is the creation of Heritage Action Zones. These aim to unleash the power of England’s historic environment to create economic growth and improve quality of life. Historic England is doing this through joint-working with local authorities and heritage groups, grant funding and sharing its skills to kick-start regeneration and renewal of declining areas, whole towns, or conservation areas.

So far, 10 Heritage Action Zones have been created. They are in Appleby, Coventry, Elsecar, Hull, King’s Lynn, Nottingham, Ramsgate, Sunderland, Sutton and Weston-super-Mare. Applications for the second round of Heritage Action Zones have now closed and those that were successful will be notified by the end of this month (October). It is anticipated that the Heritage Action Zones will begin delivering their plans in April next year.

The Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) is still making a significant contribution to much of the heritage work carried out in the UK.

Since the Lottery started in 1994, HLF has made almost 51,000 awards totalling £7.7billion. Its budget this year is £375million. But its future is not certain. The Department for Culture, Media & Sport (DCMS) is conducting a ‘tailored review’ of HLF and the National Heritage Memorial Fund (NHMF) that administers it.

DCMS has promised a robust challenge to the continuing need for the NHMF and the HLF. And even if it considers their functions should continue, it will explore alternative ways of delivering them than through the NHMF, which is a public body. Privatisation could be on the cards.

They scrub up well

Cleaning stonework not only makes it look better, it helps preserve it. Grime and biological growth such as algae and lichen retain moisture – and moisture is usually the main cause of stone decay.

Surface contaminants can also block the pores in stone, trapping moisture inside it for longer than if the surface were exposed to the air.

Cleaning limestone and granite is well established, and the received wisdom that cleaning sandstone accelerates decay is under review thanks to the work of Dr Marta Zurakowska (see below).

There is not, however, a convenient one-size-fits-all solution to stone cleaning. It is important to identify the stone to be cleaned and the type of staining. Or, if it has been coated with something (paint, perhaps) what kind of coating it is and its chemical constituents.

The building pictured here is an art gallery in Wolverhampton that has been cleaned by Relko Group. It is Bath Stone and the work involved some repairs to the stone, with Top Bed Stoke Ground from Bath Stone Group being used for indents of a scroll bracket, dentils and a stringcourse. Mortar repairs were also carried out using Bath Stone dust in a premix repair mortar. Hydraulic lime with washed sharp sand was used for repointing.

For cleaning the existing masonry over an area of about 300m2, which was heavily soiled with pigeon droppings with areas of biological growth, a sensitive conservation masonry cleaning technique was essential, so Relko used the Doff super-heated water system from Stonehealth.

Stonehealth is a major supplier of stone cleaning equipment, which also includes the Torc gentle abrasive system, the Cleanfilm latex system, which is particularly good for removing smoke deposits from fires, and a variety of poultices and chemicals for specific stain removal such as that left by metals.

A major competitor of Stonehealth is Restorative Techniques, which has its own superheated water cleaner called Thermatech and a gentle abrasive system, called Vortech, as well as its own latex, poultice and chemical cleaners. Its latest update of the Thermatech is the Inox, which is taking Restorative Techniques into new areas of cleaning. It has been used in America to clean an historic submarine and in Coventry for cleaning vintage Dakota aeroplanes.

Other companies, such as Hodge Clemco and Tensid, also sell various abrasive, steam and chemical cleaning systems.

And the National Association of Memorial Masons (NAMM) is considering going more commercial by encouraging its members to offer a stone cleaning service using dry ice (which is frozen CO2) delivered by a Kärcher compressed air system.

And the National Association of Memorial Masons (NAMM) is considering going more commercial by encouraging its members to offer a stone cleaning service using dry ice (which is frozen CO2) delivered by a Kärcher compressed air system.

CO2 is called dry ice because it does not have a liquid stage. Carbon dioxide freezes at -79ºC. The ice can be purchased commercially in insulated containers that cost about £250 for 350kg, which would be enough to clean several memorials.

Cleaning with dry ice is not new. It has been used as a cleaning system for many years in locations that include London Underground stations because it does not involve water.

The ice blaster uses compressed air at a pressure of 7BAR to shoot 3-6mm pellets of dry ice at the surface to be cleaned. The ice first freezes the dirt, which makes it brittle and causes it to crack, then the pellets dislodge it.

NAMM members were shown the system by Dorothea Restoration, which regularly uses it for cleaning metal, at the memorial masonry department in Nottingham of NAMM member A W Lymn in August.

In situ, non-invasive microscopy could provide on-the-spot stone analysis

Dr Marta Zurakowska, based in Scotland and trading as UK Stone Doctor Ltd, earlier this year challenged the view that cleaning sandstone necessarily accelerates its decay. Here she says while stone analysis is important when repairing and cleaning stone, it often could be carried out quickly on-site.Stone analysis in buildings is for many professionals a pain in the neck. It is an extra cost that often seems unnecessary and often does not even explain the causes of decay nor the solution to them.

Le Corbusier, probably the most famous of the Modernists and the designer of many concrete buildings, postulated that natural materials, which are infinitely variable in composition, should be substituted by materials of known and consistent qualities (such as concrete), although time has shown that concrete is no more consistent over its lifetime than stone.

The United Kingdom is endowed with an outstanding variety of good building quality sedimentary, igneous and metamorphic rocks that have been used over centuries as a construction material. These stones weather with the passing of years and some of them might need replacing in a building, partially or completely, either for the structural integrity of the structure or to preserve its architectural aesthetic.

In either case the stone must match the original, and identifying the original might require some scientific analysis of the material.

The main problem with stone analysis is the translation of the geological jargon for practical stone conservation. This article shows examples of two stone types with infinite variations and explains the practical meaning of petrographic examination.

The conservation and preservation of natural building materials is difficult because of the infinite variability of the material. Moreover, stone decay can be accelerated by a lack of awareness about the properties of natural stone and the consequent use of an inappropriate stone for repairs that does not match the original material, and/or its use in inappropriate ways.

Stone set in a building is subject to multiple weathering and degradation mechanisms that vary with the stone, mineralogy, porosity, climate and environmental conditions. And environmental conditions can alter on different parts of a building, with the building itself creating micro-climates that can sometimes protect stone and sometimes accelerate its decay.

What are the techniques available for stone examination?

The most common is optical microscopy – petrographic examination. Technical petrographic descriptions of natural stone are provided by British (European) Standard BS EN 12407:2007 Natural Stone test methods.

Stone is sampled from a building and a 'thin section' prepared for examination under a petrographic microscope.

A thin section is a portion of a rock mounted on a glass, mechanically polished to a thin sheet and usually protected by a glass slide cover. The thin section has a thickness of 30µm (microns), which is thinner than a human hair – thin enough for light to pass through so we can see the structure of the stone under a microscope.

We can look at the minerals and structure of the rock in relation to the scope of the study.

Other methods include X-Ray diffraction (XRD), x-ray fluorescence (XRF) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM). These allow us to establish mineral phases and quantify and map minerals and chemical components, pores, cement and texture.

This article highlights the properties of the two most common stone types in Scotland: granite and sandstone.

Granite is an igneous rock with visible grains mostly of quartz, feldspar and mica, and sometimes other minerals. Hard and durable, almost impermeable, granite has been used commonly in Aberdeen, which is sometimes known as the 'Granite City'.

Greyish in appearance, the locally quarried granite was used extensively in the city along with other granites imported from Northern Ireland and the USA.

The largest granite building in the UK is Marischal College in Aberdeen. It is built from two types of granite: Rubislaw and Kemnay. This outstanding construction in the heart of the Granite City was cleaned several years ago following petrographical analysis of the fabric of the building and trials to determine the best way to clean it.

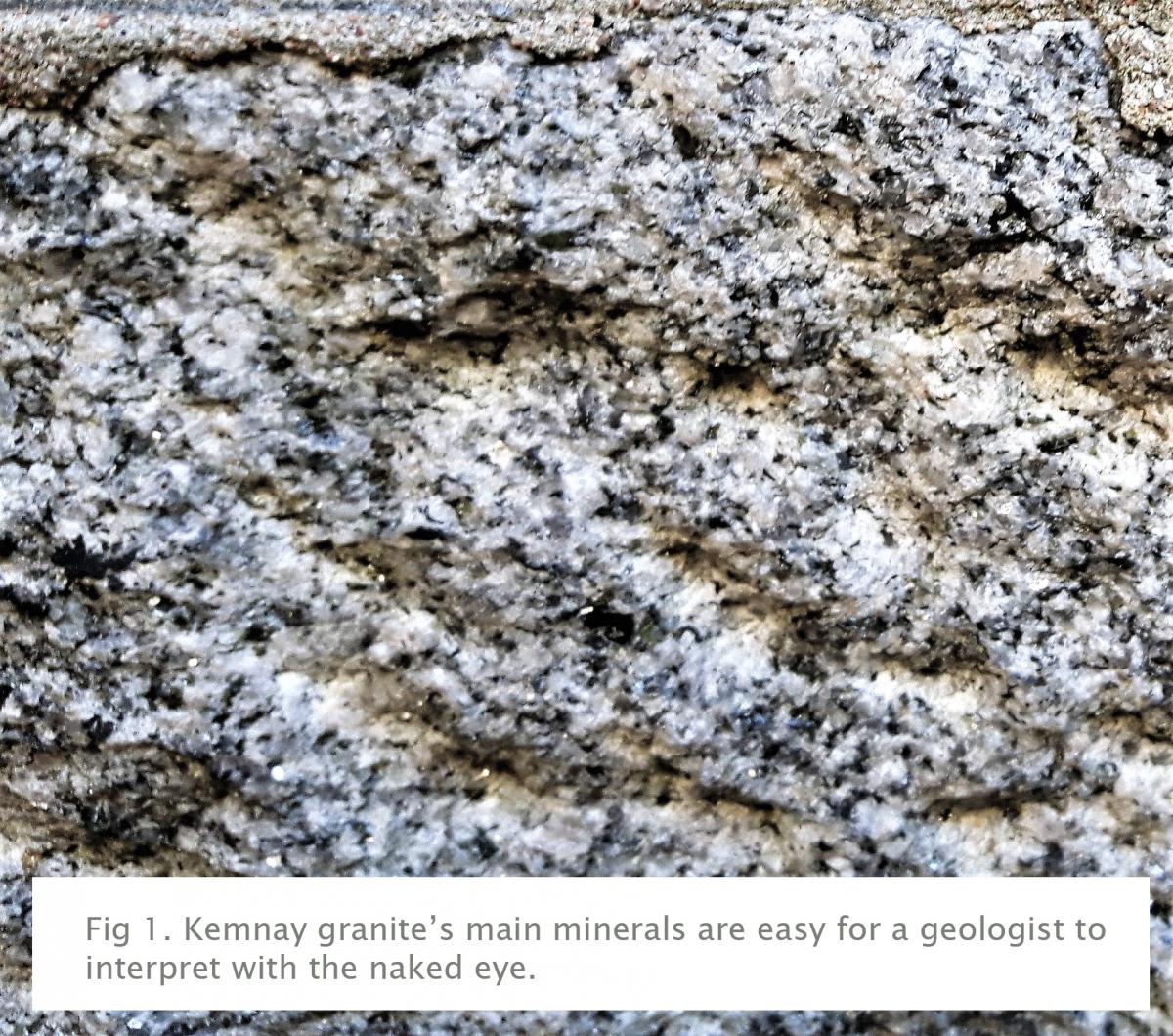

Samples of Kemnay granite (Fig1) show it is a medium- to coarse-grained granite, generally uniform, with large whitish feldspars commonly up to 5mm with finer grained crystalline intergrowth of white feldspar. It has translucent grey quartz and generally small flakes of black biotite mica. Less common white mica (muscovite) is also present. Overall the granite has a light grey, translucent appearance, speckled with black biotite mica.

Samples of Kemnay granite (Fig1) show it is a medium- to coarse-grained granite, generally uniform, with large whitish feldspars commonly up to 5mm with finer grained crystalline intergrowth of white feldspar. It has translucent grey quartz and generally small flakes of black biotite mica. Less common white mica (muscovite) is also present. Overall the granite has a light grey, translucent appearance, speckled with black biotite mica.

As the main minerals can be easily recognised in situ on the building by a geologist, further analysis might not be necessary. Unfortunately, that only works for granites or other particularly durable stones.

The porosity of granite is usually below 1%, whereas sandstone porosity can quite easily exceed 15% and usually does.

But what does that mean?

Pore space in stone determines how fluids circulate within the stone. That circulation of moisture can lead to stone weathering and decay. This is of significant importance in the consideration of stone cleaning methods.

It is much more difficult to specify the method to be used for cleaning sandstone than it is for granite. Analysis of the stone should always be undertaken before developing a conservation plan for cleaning it.

In the UK, each region characterises different geology and locally sourced stones will have different properties. Stone can vary significantly – even within one quarry. Edinburgh and Glasgow, for example, are both constructed mostly from sandstone, but different characteristics are reflected in the durability of the stone.

Edinburgh’s sandstone mostly consists of durable quartz arenite with silica cement. It is not as susceptible to weathering and decay as the sandstone in the west of Scotland, where it comprises weaker minerals including feldspar, clays and calcites. It is often cemented by these weak minerals.

Let’s see the partial, typical petrographical description of the sandstone commonly found in Glasgow, taken from the project of stone matching for repair works in the city: fine to medium grained quartz arenite with open texture, thin parallel beds of finer grain size. Porosity highlighted by blue dyed resin, bimodal grain size, coarse grains size: 200-400µm, fine grains size: 70-110µm. Grain contacts: sutured tangential and long. quartz grains are monocrystalline, varying in shape from subangular to subrounded, modified by epitaxial authigenic quartz overgrowths. Quartz grains have a thin rim around the grain, probably composed of iron oxides, which are giving the distinctive red stone colour. Minor framework minerals: feldspar (microcline and plagioclase) with some grains weathered. Other minerals: Iron oxides and hydroxides (opaque minerals), size 50-125µm, and clay minerals of very fine material filling the pore space.

That might not mean much to those who are not geologists. But the general message from that description in relation to stone repair or preservation is that this sandstone is prone to accelerated decay in the presence of water (swelling clay minerals cause intense granular disintegration and stone buckling).

Therefore, that type of sandstone should not be cleaned using a lot of water and should certainly not be saturated. The stone is Locharbriggs, a red sandstone quarried near Dumfries. It has been used for buildings in Scotland and England and is commonly used as a building cladding.

If that all seems too complicated and time-consuming, are there alternatives?

Imagine the possibility of stone analysis in situ using a portable microscope.

This new approach can be used easily on site to confirm (or not) the stone type if we already know from historical records or surrounding buildings what the stone is likely to be.

The handheld microscope, with a powerful magnification of 220x, is connected to a laptop or tablet and can give an immediate answer about the main minerals of the stone and about its texture.

Using this device allows me to measure and record details of the stone on a building – the grain size and grain contacts – and correlate that information with the evidence of stone deterioration to give the essential data for the stone conservation project.

Moreover, the microscope allows me to establish additional features of the fabric of the building – for example paint, soiling and crust penetration within the stone – all without sampling or drilling holes in the walls.

In situ microscopy is a way of achieving an understanding of a building quickly, while you are on site, especially on problematic sites where maybe more than one stone type was used, or where taking a stone sample is not possible. It can also be used where the stone source is known (or suspected) and just requires confirmation.

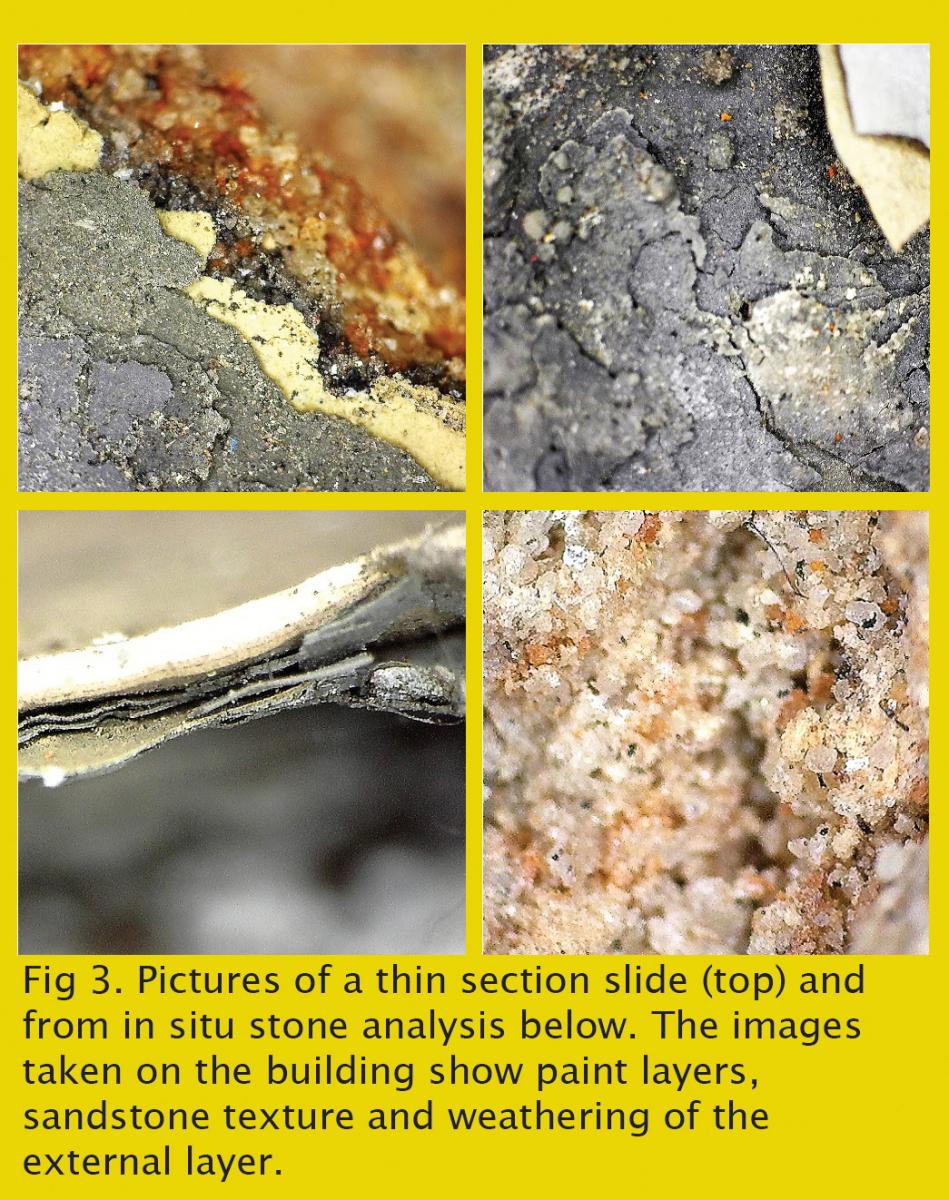

Two sets of images (Fig 3) show the comparison between a thin section slide (at the top) and an in-situ non-invasive test (below). They show a similar type of information – confirming layers of paint, grain shape and size, loose grains and the degree of weathering.

Two sets of images (Fig 3) show the comparison between a thin section slide (at the top) and an in-situ non-invasive test (below). They show a similar type of information – confirming layers of paint, grain shape and size, loose grains and the degree of weathering.

Stone analysis in general but particularly using in situ microscopy, requires further development. But with technological progress, we are getting closer to fast, cheap and reliable building fabric analysis to help with the conservation of the UK’s built heritage.