Report : Housing

A significant part of the demand for stone in housing comes from the repair, maintenance and improvement (RMI) sector. Even quite modest stone houses contribute to the geological and historical significance of areas. Here we look at the masonry and history of two such stone houses.

Glebe Farm, Wiltshire

Remember Martin Robins? He was the rather maverick force behind Farmington Quarry until he decided to take early retirement in 2005. He had some fairly unconventional, not to say confrontational approaches to promoting the stone, especially when he compared it to Bath stone and upset some of the producers of Bath stone.

These days he lives as quietly as he is ever going to in a house called Glebe Farm in Lower Stanton St Quintin in Wiltshire. According to a date over the front door, Glebe Farm house was built in 1582.

Martin is only the third ever owner of the house because until recently it was part of the 13,000-acre estate of the Earl of Radnor and was rented to tenant farmers.

It was built of what is described in old geology books as the finest cornbrash in the county. The stone was taken from a small quarry near Glebe Farm house. The evidence of the quarry can still be seen, although it is overgrown these days. Presumably the stone was used for the building of the Earl’s own house, Draycott, which was demolished in the 1950s.

The stone was even transported 10 miles or so to Corsham to be used for building Corsham Court in the same year that Glebe Farm house was built. Taking building stone 10 miles was uncommon at that time because of the difficulty of transporting it.

It was used later to build the Alms Houses in Corsham and for subsequent repairs.

At one point, a nephew of the Earl of Radnor wrote an exceptionally polite but nonetheless stern letter to a neighbour whose servant was helping himself to stone from the quarry that had been extracted to carry out repairs to the Alms Houses.

Glebe Farm house as it is today has been connected to what was once a barn behind, built of the same rubble limestone walling. The stone is in remarkably good condition in spite of having stood there for well over 400 years.

You do not have to dig down far to find the stone in the ground, as Martin discovered when he dug a swimming pool in his garden. Fortunately, friendly local farmers took the rock away to use as hardcore for cow hardstandings.

To get the diggers in to excavate the hole for the pool and remove the rock, a garage wall at the back of the house was demolished and has subsequently been rebuilt.

The rock under the buildings is one of the reasons the house is in such good condition – there has been hardly any movement of the walls.

Another reason is that the walls are about a metre thick. The stone is porous, like any limestone, but moisture does not penetrate to the interior of the house through metre-thick walls.

The stone is known as cornbrash from the soil that results as it breaks down over the eons and mixes with sands and clays. The farmers in the region had clay on either side of them, but in this area the soil was this ‘brashy’ mixture that was welcome because it was good for growing corn, hence the name.

Martin Robins, an accountant, bought the house before he went to help out landowner John Barrow at Farmington quarry because the stone business was struggling at that time. It was Martin’s first encounter with the stone industry but he says his 14 years at Farmington gave him a better understanding of the stone in his cottage.

“When I retired, having worked in the industry, you knew where to go for reclaimed stone when you needed it and you knew how to build with it.”

The Farmington quarry is at Northleach, near Cheltenham. Under Martin’s management it developed a significant fireplace business (“Shops pay better than builders,” says Martin) although the quarry still provided stone for masonry and walling. Martin says the down side of natural stone fireplaces for the domestic market was that they were expensive and marketing them was expensive. Nevertheless, the business was profitable and turnover grew to nearly £4million a year.

“The big issue then was how to produce enough stone,” says Martin. It was a problem resolved after he had left by the crash of 2008, which reduced demand somewhat.

In 2005 Martin was 55 years old and decided he did not want to spend another 10 years working 12-hours-a-day in the quarry, although he was proud of what he had achieved there and says he left a profitable business that punched well above its weight.

John Barrow’s son, Richard, took over the management of the business and the quarry has supplied walling stone, ashlar and masonry for some major residential and commercial newbuilds in the past few years. But Martin says: “I don’t regret backing out – it’s a treadmill.”

Martin was chairman of another company for a while after Farmington but says there has been enough work to be carried out on his cottage to keep him busy and that he is “seriously addicted to swimming”. “You always feel better after a swim,” he says, “even in winter.”

Being a Listed building, all the work Martin has wanted to carry out on his home has needed planning permission. That has not always been easy to obtain… but Martin relishes a battle. He has on his side a retired builder, Max Hayes, who is 79. Max has also carried out most of the building work, assisted by David Llewellyn, who is 69.

Max retired 15 years ago and since then has applied for 70 planning applications on behalf of other people, half of them for Martin Robins at Glebe Farm. “We have been successful in every single one of them,” he says. He attributes that to knowing the Building Regulations as well as the law. “I know a lot of builders,” says Max. “They come to me for their planning permissions because they don’t know how to go about it.”

Sometimes it is just a question of time. Martin wanted to create a sunbathing area on top of his garage with stairs going up to the roof from the swimming pool. He wanted railings up around the edge of the garage roof to make it safe. It has taken nine years, but when the rules regarding Listed Buildings changed in 2013 so that parts of a building could be de-Listed, Max succeeded in getting the garage taken off the Listing so the work could go ahead. It has now been completed.

Just lately a plaque has been unveiled on the house by Air Commodore J Symonds. Carrying the RAF insignia, it commemorates Squadron Leader C T White, MBE, who was billeted at Glebe Farm with his wife and son during World War II while serving at RAF Hullavington.

Martin was given a painting of his house with a car parked outside it by the son of the Squadron Leader. Martin is interested in old cars and was keen to trace the original, a Singer, but it turned out to have been copied from a Players cigarette card by the artist.

Squadron Leader White survived the Battle of Britain and D-Day but was killed on active service in the Malayan war on 8 April 1953.

Sundial Cottage, Dumfriesshire

Sundial Cottage in Penpont, Dumfriesshire, gets its name from a sandstone sundial carved by William Thomson, a stonemason, who bought the cottage in 1856. He used his skills to refurbish the cottage, adding a sandstone cantilevered spiral staircase to access two extra rooms under the roof in order to accommodate his growing family. This is an extraordinary touch of elegance that only a stonemason would or could have added to such a modest cottage.

The pink sandstone used to renew the frontage would have come from Capenoch quarry, half a mile south of the village. Some of the Penpont dwellings were built of this sandstone, including two of the village’s most impressive buildings, Capenoch House and Penpont Schoolhouse.

Darker sandstone, which was used to build Penpont Church in 1867 and some other houses in the locality, came from King’s Quarry near Carronbridge. This is a softer stone that tends to weather more readily.

Dave Hutchinson, FSA Scot, who has a special interest in vernacular buildings, points out in a paper he wrote about Sundial Cottage that the back and gable of the house, except for the Armoury, is the darker, softer stone. He says it was the norm in this area for front walls to use finer quality stone and masonry than appears in the other walls.

Even the pig-sty at the back has huge sandstone slabs, which nowadays would cost a fortune, and a slate roof with sandstone skews and ridge.

The roof of the house is slate edged with sandstone skews. The steps up into the garden are well worn, which the five Thomson boys no doubt contributed to. The sandstone paths at the front are from that era also.

The present fence would have been put there by Buccleuch estates more recently, while early photographs show the original fencing consisted of sandstone slabs with wooden fencing let into holes in it.

What has helped preserve Sundial Cottage is that in 1858 William’s fifth son, Joseph, was born there. Joseph became a noted African explorer – the Thomson gazelle takes its name from him.

It is members of the Joseph Thomson Group that have been responsible for preserving and restoring Sundial Cottage, as well as carrying out an impressive amount of work investigating and recording local history.

Apart from researching the life of Joseph Thomson, the group has conducted interviews with locals about past ways of life and researched the lives and family connections of various historical figures.

The information gathered forms exhibits in the Heritage Centre, covering subjects ranging from love and marriage to work, from village life to farming practices, from commercial to social and religious practices. The people involved range from maids to the peerage, all recorded in the written word, in images and as audio-visuals available in the Heritage Centre.

In the short-listing for the Scottish Angel Awards, the judges commented that the Joseph Thomson Group was slowly building up a network of connections that are making history relevant to all the lives of the current community.

Joseph only lived in Sundial Cottage until he was 10 years old, when his father leased a sandstone quarry and a small farm at Gatelawbridge, east of Thornhill, and moved the family there.

Dave Hutchinson reports in his paper that by the 1881 census William is described as a Quarry Master employing 58 men. In time, his son Robert took over the quarry and he and his brother William, a stonemason, went on to become partners in other quarries in the area as well and built many more stone houses.

When William left, Sundial Cottage was occupied by a Sergeant Sinclair who was in charge of the Penpont Rifle Volunteers, formed in 1860. William Thomson was contracted to add an annex to the back of the house, 3.3m wide and 4.5m long, with a door and windows that are reinforced and barred. It was for the storage of guns and ammunition.

Outside there was also a wash house, with a structure built to contain a water pump (which no longer exists) and a toilet with its door facing away from the house. It is all sandstone with slate roofs and sandstone paving.

In 1925, Jane and Doug Carson became tenants of the property, which by now belonged to The Duke of Buccleuch. Doug died in 1957 but Jean lived on there until 1996. Her 70-year tenancy preserved the cottage much as it would have been in William Thomson’s time.

It became a focus of attention when the local schoolchildren were studying the Victorian era and, as the new millennium approached, Penpont Community Council was able to secure the building from the Buccleuch & Queensberry Estate for a nominal rent so that a Local Heritage Centre could be established.

This has been achieved by the Joseph Thomson Group, which completed its renovation work in 2013.

The Buccleuch & Queensberry Estate renovated the roof and the remaining works were carried out with donations from the Leader Group, the Dumfries & Galloway Council and local benefactors.

It was officially opened by Richard, Duke of Buccleuch & Queensberry, on 29 April 2014 and was short-listed for the first Scottish Angel Awards that were presented in Edinburgh in September this year (see Report:Heritage).

Trends in the housing market

When you look at house price increases over the past couple of years it is hard to see why more houses are not being built. For six months of 2014 the annual house price inflation rate was in double digits. For much of this year it has been slightly above 5% and rose again in September to 6.1%. Builders complain about planning difficulties, but that is not really a problem as they are sitting on huge resources of consented reserves.

Even stone producers, whose projects are normally at the higher end of the market, are not too enthusiastic about the housing market at the moment. They generally say they are rushed off their feet with high levels of demand for their stone, but an increase in the amount of housebuilding is not what is creating that demand.

Even where some larger volume projects are going ahead, the builders are restricting their use of stone to the most visible houses at the front of developments.

There are still mansions being built using local stones, but housebuilders in general are unsure of the market. Given its volatility over the past few years and the regional fluctuations hidden by national figures, that is understandable.

For example, the latest figures available for house price inflation as this is being written (for the year to September) show the overall figure for the UK is 6.1%, but that hides an increase of less than 1.1% in Wales and Scotland, a massive hike in prices of 10.2% in Northern Ireland, 8.4% in the East of England but 1.8% in the North East. London saw prices rise 7.2% and in the South East it was 7.4%. In London and the South East there might actually be a shortage of consented land to build on that are stopping houses being built there.

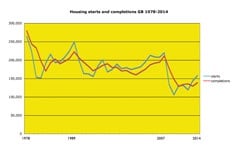

The graphs here show the long-term changes there have been in housebuilding and house prices and how the crash of 2007/8 hit housebuilding even more than did the previous price crash of 1989.

The latest figures from the National Housebuilding Council (NHC) showed a 2% fall in the number of house registrations in the third quarter of this year, although NHC said the overall number of houses built during the whole of the year was likely to be up on last year because of the increase in activity in the first half.

And Julia Evans, Chief Executive of BSRIA, the association providing specialist services in construction and building services, says: “It’s easy to forget the depths of the recession five or six years ago when the industry was only building 80,000 to 100,000 homes a year. We’re now at about twice that rate so the industry has come a long way. But there is still a long way to go if the UK is ever going to meet the target set by organisations such as Shelter. The UK should be building 250,000 new homes a year to meet the demand of those priced out of the present under-supplied market.”

Julia thinks the relatively small number of houses being built is the result of a skills shortage that she wants to see the government address by encouraging more training.