Safety & Health Awareness Day: Lose concentration and someone gets hurt

The Health & Safety Executive and Stone Federation SHAD this month (September) reminds the industry that the work environment can be a dangerous place and making it safer can be just a question of focusing on how to.

Health & safety in all sectors of the stone industry has improved a lot over the years. The industry has invested heavily in computerised machinery, gantries, pillar cranes and other lifting equipment in its factories. Waterwalls and dust extraction systems, booths for dry cutting, personal protective equipment, and a plethora of materials handling equipment for use in factories and on-site have made working in stone safer and more pleasant as well as more productive.

And yet...

There continue to be more stone workers diagnosed with long-term debilitating diseases such as silicosis and hand arm vibration syndrome (HAVS). People become deaf as a result of operating noisy machinery. There are any number of minor crush and cut injuries and a few that are life changing, even occasionally fatal. And who has not suffered painful joints, back and muscles as a result of ill advised lifting, stretching, twisting or some other awkward manoeuvre?

There continue to be prosecutions of companies whose employees are either hurt or put in danger as a result of a failure to assess risks and avoid them. And with fines now high, although at least consistent thanks to guidelines given to the courts, there is every incentive to avoid them.

That is why Stone Federation Great Britain (SFGB) works closely with the Health & Safety Executive to help the industry understand the risks and avoid them. The Federation produces publications and has a health & safety forum and hotline for its members to offer guidance and advice. And from time to time it joins with the Health & Safety Executive (HSE) to arrange a SHAD – a Safety & Health Awareness Day. The latest was on 18 September at SFGB member Schlüter-Systems’ training centre in Coalville, Leicestershire.

SFGB Chief Executive Jane Buxey opened the event, although it was not exclusively for Federation members and included people from companies that were not members.

Andrew Bowker from the HSE provided some background. Andrew is the health & safety inspector for the metals and minerals manufacturing sector, which includes stone processing, and it is his job to engage with industry.

Stone Federation Chief Executive Jane Buxey (left) and Natural Stone Industry Training Group Training Officer Claire Wallbridge with Andrew Bowker, HM Inspector of Health & Safety, Metals & Mineral Manufacturing Sector, at the SHAD.

Stone Federation Chief Executive Jane Buxey (left) and Natural Stone Industry Training Group Training Officer Claire Wallbridge with Andrew Bowker, HM Inspector of Health & Safety, Metals & Mineral Manufacturing Sector, at the SHAD.

He said he wanted the industry itself to lead the way on health & safety because it had a far better understanding of the risks and dangers associated with the work than the HSE did and should be able to devise solutions to them, presenting those solutions in best practice guides for the whole industry to use.

This is part of the ‘Help Great Britain to Work Well’ initiative launched by HSE in 2016. Its guiding principles include promoting broader ownership of health & safety, so that industry does not see it as something foisted upon it but something of benefit to it in which it is actively involved. After all, improving working practices often results in more efficiency and greater productivity in the workplace and in any case, most employers do not actually want to see their employees hurt.

Andrew Bowker said key issues for the stone industry are silica dust, poor guarding of machinery (particularly bridge saws), poor slab storage, and poor adherence to the testing of lifting equipment required by LOLER (Lifting Operations & Lifting Equipment Regulations), as well as issues common to many manufacturing businesses of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs).

“We would like to encourage people to get involved with the Stone Federation and work together to develop some practical industry guides.” He said the industry and HSE needed to continue to work together and part of his role was to ensure it did so.

Part of the ‘Help Great Britain to Work Well’ project involves highlighting and sharing success stories. To that end, HSE is always looking for case studies where risk assessments have identified problems and resultd in them being resolved innovatively. “And don’t think your company is too small to be of interest,” said Andrew as he encouraged stone companies to come forward with examples of their own solutions to health & safety issues.

Andrew said that although he was focused on the manufacturing side, the HSE’s construction division was concerned with the same issues. And although increased stakeholder involvement in health & safety was important, the HSE continued to be a prime mover and would enforce the law when that was required.

He said the UK’s health & safety record compared well with that of other countries, but there had still been 15 fatal accidents in UK manufacturing in general in 2017/’18 and 60,000 non-fatal accidents.

Another HSE initiative is ‘Go Home Healthy’, which focuses on lung disease, MSDs and work-related stress, all major causes of both short-term and long-term injuries and of significance to the stone industry (especially the first two) with its high silica-content products (sandstone, granite, slate and engineered quartz in particular) and the manhandling of heavy materials.

Work-related lung disease cuts short the lives of 12,000 people in the UK every year, even though it is often after they have retired, while 9million working days are lost to MSDs when people cannot work because of back and neck injuries, pulled muscles, or other debilitating injuries often associated with lifting and repetitive strains.

Stress is a growing problem, particularly among younger workers. Last year there was a 33% increase in the amount of time taken off for mental health conditions (mostly stress) by 25-to-34-year-olds. Altogether the loss of 12million working days were blamed on stress in 2017 and Andrew said: “Mental health really is on the agenda of a lot of organisations now.”

He also mentioned a growing incidence of injuries resulting from machinery maintenance, which could well be a result of more mechanisation – a trend clearly evident in stone processing.

In spite of the growth of the stone industry, it is still a relatively niche sector. However, Andrew Bowker said: “Every year we [the HSE] identify industries that need particular attention and the stone industry has been on that list for a number of years.”

He said there had been 200 proactive inspections of manufacturing sites in 2016/’17 resulting in 100 Fee for Intervention (FFI) actions (where HSE charges the firm). In 2017/’18 there were 85 proactive inspections resulting in 45 FFIs.

Of the improvement notices issued, about 60% related to health, including 22% for poor control of respirable crystalline silica (RCS), 27% to local exhaust ventilation (LEV, or dust extraction), 23% to a lack of any kind of health surveillance and 9% to a lack of face mask fitting.

More than half of improvement notices relating to safety issues in 2017/’18 were about machinery guards (or lack of them), notably on bridge saws. There is some guidance from the Minerals Products Association on guarding bridge saws that can be downloaded from bit.ly/sawguards. There were also 36% of notices issued concerning lifting equipment that had not been checked, which it should be every six or 12 months (depending on what it is) and the checks should be recorded. There had been no stone factory prosecutions in 2017/’18 and only two the previous year.

After the introduction, those taking part in the SHAD split into two groups for a detailed look at four particular areas of health & safety: noise and vibration; assessing musculoskeletal disorders; local exhaust ventilation (dust extraction); respiratory protective equipment (masks).

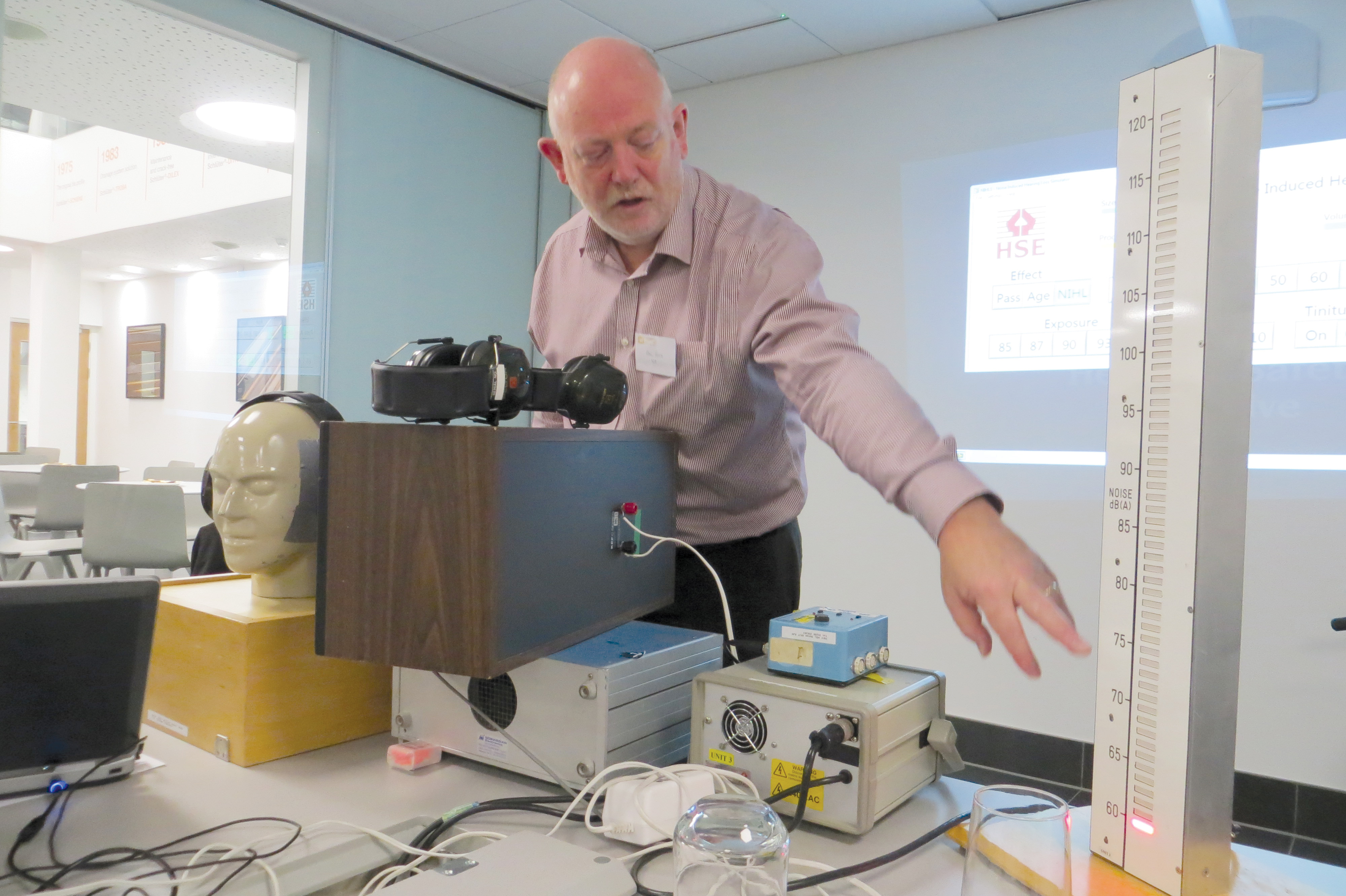

Andrew Hounslea, an HSE Specialist Inspector, and Paul Pitts, a noise vibration scientist in the HSE laboratory in Buxton, explained and demonstrated the effects of workplace noise on hearing and the loss of it.

Paul Pitts explained that we all lose some hearing as we age and played a recorded conversation with background noise as it is heard by different age groups. He then demonstrated how it would be heard by someone exposed to 12 years of working in a factory with a noise level of 96decibels (dB), which is about the noise level of a petrol lawnmower. Regular, sustained exposure to that level of noise causes some hearing loss and might result in tinnitus, which can take a lot of different forms.

Paul said using a grinder on stone produces a noise level of about 105dB, which can result in a noticeable loss of hearing after just two years of regular, sustained exposure. And it is not just volume that is lost, but also definition, making it harder to understand the spoken language.

Andrew Hounslea said the noise regulations existed to protect people from that noise-induced hearing loss. As with all health & safety issues, priority should be given to removing the risk, which in this case means reducing the noise level to less than 85dB, the level at which damage starts to be inflicted if the noise is sustained and exposure to it is regular. Health surveillance is critical and if ear defenders must be used, people need to be trained to use them properly, although “hearing protection is very much a last resort”.

Andrew said: “In stone there’s a lot of hand-held tools. You can’t control the risk of exposure to noise of using them, so it’s important that people have ear protection and know how to use it properly. And check they are using it!”

Floor-to-ceiling plastic curtains are good for containing noise levels inside buildings, he said. People have different preferences and different shapes, so it is best to offer a range of products so they can find the one that suits them best. Rather than saying what is the ‘best’ form of ear protection, it makes more sense to say what is the most appropriate form of protection.

Alison Bowry, a Health Services Laboratories (HSL) scientist, made the same point when she spoke about face masks for use as protection against respirable crystalline silica (RCS). Different shaped faces mean one mask can be better for one person and another better for another.

Alison Bowry demonstrated how important it is for face masks to fit the user.

Alison Bowry demonstrated how important it is for face masks to fit the user.

She showed a video of how RCS enters the lungs and then is trapped there. It effectively turns your lungs to stone, causing silicosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) characterized by shortness of breath and coughing that normally worsens as the years progress, and lung cancer.

Alison spoke about the importance of fitting masks properly. Those that work by forming a seal around the nose and mouth only work if the seal is complete, as she demonstrated with smoke chambers. That seal will be compromised by beards, or even stubble, so if people will not shave they have to use a full face or positive air flow mask.

When respiratory protective equipment (RPE) is introduced it should be fit-tested by a competent tester on everyone who will use it – and you can find a competent tester (Alison is among them) on the Fit2Fit website (fit2fit.org).

Only CE-marked masks should be used and once people have been issued with them they should understand the importance of using them and the dangers associated with silica dust, which is particularly prevalent with dry cutting. The use of masks should be monitored, and if the masks are re-usable they should be stored carefully and maintained regularly. Records should be kept of maintenance.

Again, masks are a last resort and the first step should always be to try to reduce the amount of RCS produced or remove it from the vicinity. One way of clearing the air in a factory is to use local exhaust ventilation (dust extraction). Dominic Pocock, another HSL scientist, demonstrated the effects of that. He showed how hoods could only capture dust from a relatively close range but their effectiveness could be considerably enhanced by enclosing the working area on five sides with dust extraction on the closed far side, creating a flow of air through the booth.

Dominic Pocock showed how dust extraction works best in booths and with industrial vacuum cleaners attached to tools.

Dominic Pocock showed how dust extraction works best in booths and with industrial vacuum cleaners attached to tools.

He said using a booth was so much more efficient than just a hood that the extraction fan needed to operate at only 10% of the speed of the fan for a hood – and it was desirable that it should so the person in the booth is not in too much of a draft and electricity is not consumed unnecessarily.

Dominic demonstrated how an industrial vacuum attachment on a tool with an appropriate guard could almost eliminate dust in the atmosphere because the suction was so close to the source of the dust. Such vacuum pumps are readily available from companies whose tools are commonly used in the stone industry, such as Flex and Makita. He said because of the silica in stone the vacuum unit would need an ‘M’ class filter.

A lot of tools used in masonry these days also have a water supply for wet working and Dominic said this was effective, reducing the amount of respirable airborne dust by as much as 95%. With wet cutting and LEV in a cabin, it is possible to keep the atmosphere outside the cabin completely free of RCS, he said. He reminded his SHAD audience that dust extraction equipment has to be tested at least every 14 months and records of the testing should be kept.

One detrimental feature of hand tools that users cannot be isolated from by personal protective equipment is vibration. HSE tests have shown gel-filled gloves do not remove users from exposure to the harmful vibrations created by power tools, although by keeping hands warm they might make the user more comfortable.

Vibration exposure can lead to nerve damage that can leave fingers unable to feel and manipulate objects. It is called Hand Arm Vibration Syndrome (HAVS), a manifestation of which can be what is called white-finger, which describes its effects. It can be painful.

Although users cannot be isolated from vibration entirely, the level of vibration can be minimised by having the tools themselves properly maintained and the discs they are using (such as abrasives and saws) properly balanced, as Paul Pitts demonstrated. He said out of balance disks are a major source of vibration.

People also tend to press too hard when using the tools, which is inefficient because it prevents the tools from working in the way they are designed to work as well as transfering vibration straight into the body of the user.

An example he gave is hammer drilling. If the user pushes the drill too hard, the hammer effect stops aiding the drilling of the hole and instead sends all of that energy back into the user. Another was of face polishing, where pushing too hard prevents the abrasive from clearing itself.

Two-thirds of cases reported to HSE under RIDOR relate to vibration injuries and Andrew Hounslea said people could suffer from HAVS even at exposure levels below the action limit. “You need to asses the risk, try to eliminate vibration at source and teach employees about vibration,” he said.

People using tools should be monitored for early symptoms of HAVS injuries and if they show any, they should be stopped from the activity causing them.

Some companies have adopted the use of commercially available exposure metres to comply with the legal limits of vibration exposure of workers. “These have their place,” said Andrew, but said some companies only seemed to use them to see how much damage they are exposing employees to. “What you need to do is record that information and take action.”

Then there are all the aches and pains collectively known as musculoskeletal disorders (MSCs). As noted earlier, these cost the country 9million lost working days a year. Lower back pain was once the most common cause of days taken off work. It has been superceded by stress as the most common reason for sick leave, but lower back pain is also no longer the most commonly reported MSC. These days, 45% of reported MSCs are upper limb and neck pains, with lower back pain at 38%. Chris Quarrie, an HSE ergonomist, thought the change was likely to be because a lot of heavy work these days has transferred to machines and people are working on computers or standing at the end of a line unloading, continually repeating the same movements.

The first question should always be: why is this action being carried out? If it can be avoided, that’s the best solution. If it can’t, can it be made easier or done in another way. Can more space be made available to make it easier for people to avoid bending and twisting awkwardly; can a simple aid be used or devised to make the job easier. An example he had come across had been where drills had been hung on wires so the weight of them did not have to be born by the user.

He said there were usually ways to overcome and avoid the actions that would cause MSD. Training people how to do the same job better was probably not the ideal solution and should be a last port of call, not the first thought.

“Training is only superficial risk reduction,” said Chris. “You need to eliminate the risk at source if you can.” That, he said, is the point of risk assessment and he introduced a document produced by HSE called ‘Manual Handling Assessment Charts’, which guides you through risk assessments using a simple traffic light system to produce a score. “You don’t have to have full automation, just do things that will make a difference.”

At the conclusion of the SHAD, Andrew Bowker said he hoped all those who had taken part would, as a result, return to their companies with at least one idea that they could use to improve the way they work.

The HSE website includes help and advice specifically for stone companies, including a wide range of publications that can be downloaded free. Explore it at www.hse.gov.uk/stonemasonry.