Stirling Prize: William Anelay project is winner

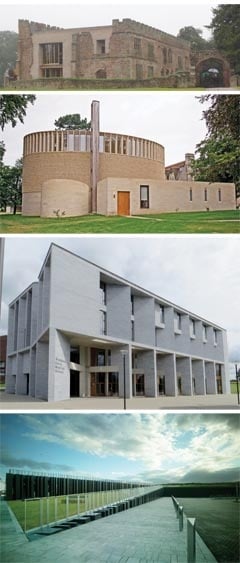

This year’s Stirling Prize, one of architecture’s highest awards, has gone to Astley Castle, a stone project where specialist building and conservation company William Anelay helped create a new-build within the walls of the castle ruins. Three of the five other projects on the short-list for the Award also showed some of the stone industry’s finest work.

Astley Castle in Warwickshire is a fascinating combination of new-build within the singularly historic walls of a castle once occupied by Lady Jane Grey, the nine-day Queen executed by her successor, Queen Mary, in 1554.

This magazine described it as “conservation through re-use” when it featured the project, then in progress, two years ago (see NSS July 2011). It clearly impressed the architectural elite of the Stirling Prize judges this year and the 27% of 65,000 people who voted for it in a much publicised BBC website poll.

The castle had become a hotel by the time it was gutted by fire in 1978. After the fire it was left derelict. It deteriorated to the point where English Heritage put it on its ‘At Risk’ register as a priority.

In 2007 the Landmark Trust stepped in to save what was left of the moated castle built of a local sandstone. It held an architectural competition to design a new building to go inside the ruins so the ruins themselves could be preserved. The aim was that it should become a holiday let, which it has.

The work undertaken by York and Manchester-based specialist building company William Anelay under the direction of architect Witherford Watson Mann, involved conserving original 12th century stonework and using it, along with glass and brick, as the walls of the new-build while leaving the building to be read as a ruin. More than 270 Cintec anchors were inserted into the existing remains to make the building safe and help to stabilise it.

The Chairman of William Anelay, Charles Anelay, the eighth generation of his family to be involved in the 266-year-old business, said on hearing the result of the Stirling Prize: “This is the ultimate accolade for William Anelay for what was one of the most complex and challenging projects we’ve ever worked on.”

Anelay’s MD, Tony Townend, added: “The project clearly struck a chord with the UK public and we’re delighted that it has been recognised in this way.”

The work has been carried out to an exceptionally high standard, using large expanses of glass to allow the original fabric to be seen from the inside and out.

Bedrooms are on the ground floor while the open upper room has an exposed timber roof. It is unequivocally modern but with the character of a medieval banqueting hall.

It might have been considered brave to have built a structure so modern inside such historical walls, but fortune favours the brave and the result could provide a model to be followed by others in the heritage sector.

William Anelay Technical Director Tim Donlon says: “I’ve worked on many historic and incredible projects with William Anelay but this really has been the most challenging and interesting one yet.

“There were so many different facets to this project that made it unique. The whole of the new build is enclosed within the existing ruins. In order for the new walls to meet the ruins at the correct roof level all of the setting out has been established from the top, rather than from ground level, using just two precisely defined points on the existing structure as a starting point.

“There’s also a brickwork bond devised by the architect specifically for this project, which has never been used before and involved almost 50,000 40mm bricks imported from Denmark.

“Everything was so exact that being just a millimetre out could have effected everything. The architect’s plans were extremely detailed – every single brick is shown on the drawings.

“At every point where new ground was broken we had to call in the archaeologists.

“There are so many layers of history here. From the 12th century onwards, additional aspects have been added. It reveals a lot of fascinating construction methods from days gone by as well as some rather shoddy Victorian workmanship.”

Alastair Dick-Cleland of the Landmark Trust is delighted with the result. “This project really stands out. We would normally do a traditional restoration… this is a first for the Landmark Trust and is a practical solution to saving what was a very ruinous structure. Without this intervention, Astley Castle would surely have been lost forever.”

The three other stone projects short-listed for the Stirling Award (also pictured here) were the Clipsham limestone Bishops Edward King Chapel at Ripon Theological College in Cuddesdon, Oxfordshire; the basalt Giant’s Causeway visitor centre in Northern Ireland; and the Irish Blue limestone Graduate Entry Medical School at Limerick University in Ireland.

The Giant’s Causeway visitor centre was featured in the August issue of this magazine last year and the other two projects will be reviewed in the coming months.