Stone in hard landscaping: SuDS or floods

As flooding once again hits communities all over the UK it is clear it is a growing problem. Yet sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) tend to be an afterthought in most hard landscaping in England, in spite of the Flood & Water Management Act 2010. It is time to think again.

You might say it’s the perfect storm. Temperatures are increasing and warmer air can hold (and drop) more water. At the same time more land is being covered with impermeable paving, both as a result of the growth of cities and urbanisation and the covering of gardens in hard surfaces so cars can park on them.

We have seen the results. Water runs into water courses and causes them to flood. Or it rushes towards the lowest point in an area causing a flash flood.

Flooding is devastating for households and businesses effected. And expensive. The Environment Agency has estimated the floods in the winter of 2015/16 caused £1.6billion worth of damage. Some insurance companies put the cost at more like £5billion, not all of it covered by insurance because it is either not available or too expensive for households and companies in flood prone areas. There are said to be more than five million properties in such areas that are now considered to be in danger of flooding.

Some of them were flooded during 2019. According to the Met Office summary of the year, notable extreme events in 2019 included heavy rainfall in February, March, April and June, with numerous incidences of flooding from the end of July onwards. The UK was hit by five named storms and towards the end of the year flooding was exacerbated by the fact that further rainfall was falling on to already saturated ground.

There were also record-breaking warm spells in February and July and for both the Easter and late August bank holiday weekends. Temperatures exceeded 30 °C somewhere in the UK on 10 days during the summer. As a whole, 2019 was the 11th warmest year in a series that starts in 1910. The 10 hottest years have all been since the turn of the millennium.

The rainfall total aggregated for the whole of the UK for 2019 was 1240mm, which is 7% more than the 1981-2010 average, making it a wet year for the country, but not especially so.

However, the rain did not fall evenly and parts of the North Midlands, South Yorkshire and Lincolnshire were notably wet, while Sheffield recorded its second wettest year in station records that date from 1883. On the other hand, parts of northern Scotland and East Anglia were slightly drier than average.

The industry providing hard landscaping could help to reduce the threat of flooding and sometimes does – but not often enough, according to many, even plenty within the industry itself.

One of the reasons landscaping is not used to alleviate the problem is often because the person or organisation paying for the landscaping is not the person who suffers the consequences of flooding.

The person paying for the landscaping does not want any extra cost that might be involved in creating and (importantly) maintaining sustainable drainage systems (SuDS) that provide an alternative to the direct channelling of surface water through networks of pipes and sewers to nearby watercourses.

Chris Griffiths has been SuDS Marketing Development Manager at Marshalls since 2011. Marshalls is a major force in hard landscaping, operating 19 quarries in the UK as well as importing stone from Asia and providing a range of concrete, clay and porcelain products.

Chris says while we can’t stop the rain, we can change the way we carry out developments by using SuDS.

He says SuDS presents opportunities for reducing pollutants and creating pleasant, attractive spaces in which people can relax and enjoy themselves.

The four pillars of SuDS, which Chris says should be balanced evenly, are quantity (dealing with the volume of water), quality (cleansing the water that flows through the system), biodiversity (improving habitats for diverse planting and wildlife) and amenity (creating pleasant, lush environments for people to spend time in).

The need for SuDS is likely only to increase with climate change and more housing and urbanisation.

The law

Provision for SuDS and the national standards required for their design, construction, maintenance and operation were included in the Flood & Water Management Act 2010.

In Scotland and Wales SuDS is compulsory, but in England the government decided not to implement Schedule 3 of the Act, which would have provided a comprehensive regime for surface water drainage and the adoption of SuDS.

Recognising that government has been unable to resolve the matter, the water companies have now taken the initiative and developed a solution that comes into effect this April. It will allow a whole range of SuDS features built by developers on new developments to be transferred to water companies to manage on an ongoing basis.

The water companies hope this will provide the impetus to tackle flooding using SuDS. Their motivation is that flooding is expensive for them. They believe managing some sustainable drainage systems will prove cost effective.

Giles Heap, the Group Managing Director of major hard landscaping product supply company CED, says the use of natural stone in permeable hard landscaping can be part of the solution – and CED specialises in the supply of natural stone that is often used in association with permeable landscaping systems.

Paul Wagstaff, Head of Product Management at Aggregate Industries UK, says drainage design should be integrated into a project at the start of the feasibility stage of every project as the key to speeding up a SuDS revolution.

In December, following the deluge of October and November that resulted in widespread flash flooding across many parts of the UK, Paul said: “Sadly, amid the ongoing climate crisis, the flood threat is set to increase – those were the words of the Environment Agency (EA) Director of Flood Risk Management, John Curtis, who recently admitted that the flooding is likely to get much worse and happen more frequently.”

Yet Paul says despite the stark risk presented by flooding, the mitigation efforts around it have so far been limited. “Although the government passed a new law requiring all new developments to include sustainable drainage systems in 2010, it quickly put the rules on hold in a bid to help developers to keep costs down and speed up house-building rates.”

In England the revised National Planning Policy Framework states that major developments should incorporate SuDS... unless it would be inappropriate to do so.

The Flood & Water Management Act did introduce into law the concept of flood risk management rather than flood defence. But Paul Wagstaff says flood defence measures have been typically overlooked in the building planning process, often being left as an afterthought in the final design stages, forgotten entirely or fitted retrospectively after a flood has happened. He says SuDS is under-used as a starting point for projects that involve hard landscaping.

Typically, a SuDS will use a combination of water practices to form a management system. This could include a landscape designed to intercept and retain rain and pre-treatment steps such as planted with reeds to help remove pollutants.

This could be supported with retention ponds, providing storage and treatment for excess water, and infiltration systems, such as trenches and soakaways.

In order to maximise a SuDS potential, it should be supported with the use of permeable surface material options.

Paving designed to direct excess water off streets, parking surfaces and driveways into drainage systems could be used in conjunction with a porous surface that allows water to pass through the material into an underlying permeable sub-base.

“Of course,” says Paul, “this approach does require investment; but it can deliver benefits on multiple fronts. When formalised as an integral part of the design process, good SuDS can significantly help control run off and reduce peak flows, therefore reducing the risk of flooding while also improving the water quality with the removal of pollutants.

“Plus, in terms of sustainability, SuDS design can create new habitats and rehabilitate or enhance existing ones, benefiting the landscape and community while helping developers tick the ‘green box.’

“As we look to the future, the only way to tackle the current housing deficit will be to build more, but with flood incidents only set to increase it will become ever more important for preventative measures to be incorporated into the inaugural development stages.

“Furthermore, with the government currently working on the latest draft of its Flood & Coastal Erosion Risk Management Strategy, and flood-risk becoming an even more prominent consideration for would-be house buyers, the issue isn’t going to go away.

“For that reason it is time for housebuilders to invest in good SuDS en masse and protect homeowners from flooding.”

Paving setts & kerb stones landed in the UK

There are no figures for the amount of indigenous stone produced in the UK and Ireland, let alone the proportion of it used in hard landscaping. Anecdotally, the use of indigenous stones is growing. There are England’s sandstones, including Yorkstone and Pennant, granite and slates, and even some of its limestones. From Scotland come a variety of stones such as its Caithness sandstone, Green Schist, Whinstone and Grampian granite. And from Ireland, the hard blue limestone is widely used for hard landscaping, including street furniture, as well as its granite.

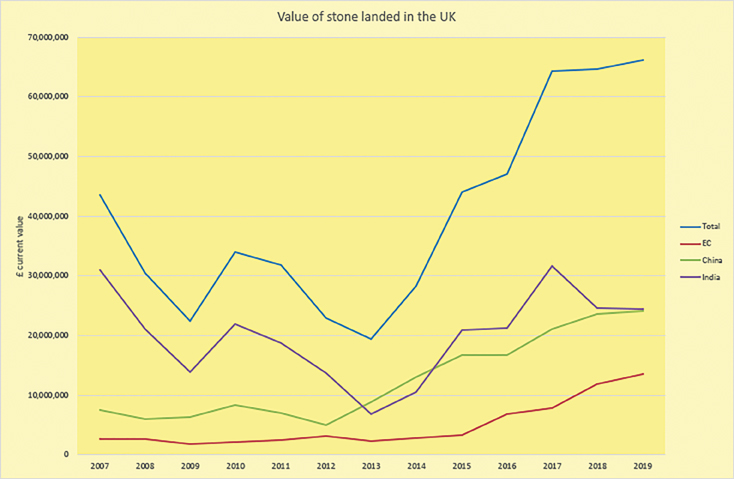

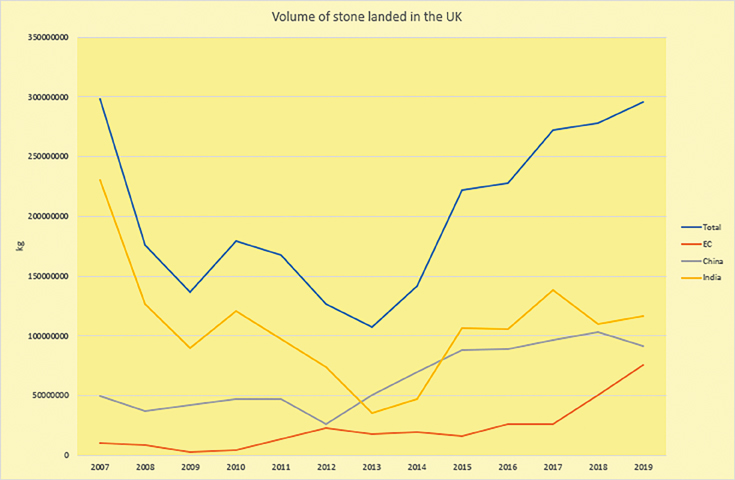

Nevertheless, a quick review of hard landscaping projects that use stone clearly indicates most of what is used is imported, a lot of it from India and China, although an increasing proportion from Europe since the market entered a period of sustained growth after 2012. Spain, Portugal and Italy (in that order) account for almost all of the arrivals from Europe, with Portuguese granite having a growing significance. The reason more is coming from Europe is both a question of taste and practicality. Although there are sizable stocks of Indian stones (in particular) in the UK, anything not already landed can take six or eight weeks to arrive from the Far East. Stone for many projects is ordered too late to accommodate that time scale, so those supplying the project turn to Europe. The mean price of stone from Europe fluctuates a lot more than the means from China and India, which is largely a reflection of the stones chosen and how they are used. China and India supply mostly sandstones and granite and the aggregated price per tonne does not vary greatly from year to year. In Europe, the mean price can vary considerably because the market for natural stone hard landscaping is relatively small and one or two large projects in any particular stone can have a significant impact.

The usual caveat applies to these figures: they are compiled from VAT returns so some stone will go unrecorded as it is imported under different codes.

Please note: The figures for 2019 are provisional and will increase in the coming months as more returns are added.