Cover illustration: © Ed Kluz 2019

Having completed a doctoral thesis on medieval sculpture, Alex Woodcock wanted to carve the stone for himself. And so began his life as a stonemason and carver. Eric Bignell reviews his book that tells the story.

- King of Dust – Adventures in Forgotten Sculpture

- ISBN: 9781908213693

- Author: Alex Woodcock

- Published by: Little Toller Books

- Pages: 192

- Illustrations: 34

- Price: £16

After three-and-a-half years of study, Alex Woodcock had become a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD). But he was suffering from depression. He did not want to hide that fact when he wrote the story of his life as a stonemason and carver in a book called King of Dust – Adventures in Forgotten Sculpture. But neither did he want it to be the theme of the book.

He says: “It was an important part of the story. Working stone taught me to think in a different way. It helped with the depression, not in an immediate ‘I’m transformed’ sort of sense, but over time. It gave me a bit of space, I think, and taught me as much as my PhD – more, perhaps.”

The depression is not presented as an issue in the book. It is there as a matter of fact because it was part of his life and an influence on it when, in his 30s, he decided to train as a stonemason with Weymouth College after experiencing the pleasure of carving stone on a short course.

King of Dust will inevitably be compared with Andrew Ziminski’s The Stonemason (reviewed in NSS May 2020). Both are set largely in the West Country and both are reflections on a career in stonemasonry and carving. What ties the chapters in Andrew’s book together is the year in which the book is set. In Alex’s case, the cohesion comes from Romanesque carving.

Both books are personal journeys, providing an opportunity to explore and philosophically reflect upon architecture and history, geology and geography in terms of stonemasonry and carving. There is even a bit of genealogy in King of Dust as Alex discovers his great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandfather was a stonemason.

Alex Woodcock at Exeter Cathedral, where he worked as a stonemason for six years.

Alex Woodcock at Exeter Cathedral, where he worked as a stonemason for six years.

King of Dust was published in 2019, before The Stonemason, and Alex did manage to get to some literary festivals in the West Country to promote it before Covid-19 brought such activity to a halt, whereas Andrew’s book signing tour planned for last year had to be cancelled. Both books are due out in paperback this year.

It is unusual for people who work with their hands to have their voices heard through literary undertakings – and both these books, in their individual ways, present stories that are a joy to read for their literary merits irrespective of an interest in stone and working it.

Connecting with stone

The fact that they are about stone and masonry is, nevertheless, an important part of their attraction. As Alex Woodcock says in King of Dust: “There is a mystical pull to stone. It is the raw material of the earth, a handshake away from the basic elements themselves. We associate it with longevity, origins. We say something is ‘carved in stone’ if it is binding and unalterable. We use it to commemorate the dead, cutting the names of the lost into its fabric, connecting them with the long cycles of geology and perhaps, by doing so, immortality. Depending on the type of stone and how it is worked it can be either low status or high status, ballast or palace. In archaeological terms it is the first age. Stone has served us since the very beginnings: tools, building materials, art.”

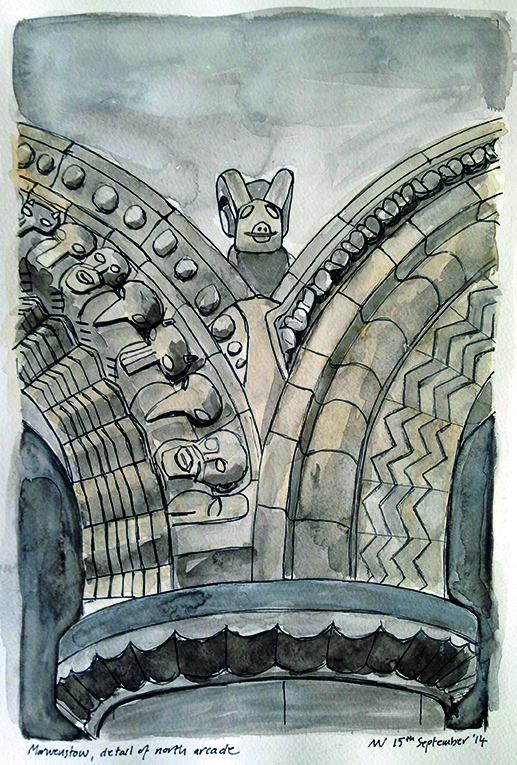

Alex Woodcock’s painting of the arcade detail of the north nave at Morwenstow, Cornwall.

Alex Woodcock’s painting of the arcade detail of the north nave at Morwenstow, Cornwall.

The books were presumably as much of a joy to write as they are to read, because both authors are planning on writing more. For Alex, concentrating on Romanesque carving in King of Dust leaves the way open for further meditations on other architectural styles he has worked with. Gothic is planned as the theme for his next book.

The fact that King of Dust and The Stonemason were published so close together amuses Alex. He sees both works being in the spirit of Seamus Murphy’s Stone Mad, published in Ireland in 1949 and later in London. The long wait followed by two at once inevitably evokes parallels with buses.

There have been a few other books written by stonemasons about their lives in the intervening years, but they have not received the acclaim of the current two.

A time for skills

Possibly now is the right time for such reflections on craft skills using a product that is for humans the quintessence of permanence; safe, secure, enduring.

The craft skills of people have also become fascinating, perhaps in reaction to everyday life that is increasingly virtual, digital, viewed vicariously on a screen rather than experienced in muscle-aching, dusty reality. After all, The Repair Shop on TV has moved from BBC2 to BBC1 because it is so popular, so clearly there is a mood in society for such reflections on traditional skills.

In 2019 lettercutter Ieuan Rees became a YouTube sensation when a video that had been recorded in 2012 when Ieuan was 71 went viral. Apparently the attraction was autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR), which is a tingling sensation created by certain sounds. The sound that apparently causes ASMR on the video is Ieuan’s soothing Welsh-accented commentary about his lettercutting and carving accompanied by the tapping of his mallet on his chisel as he cuts letters into slate.

Others simply found the video relaxing, or were inspired by his words of wisdom.

It is rumoured that two other stonemasons are currently also writing books of a similar nature, which we can look forward to seeing later this year or next.

Alex best sums up the attraction of hand skills in his final paragraph of King of Dust: “I grew up in an urban setting, a feeling of detachment perched always on my shoulder, but each carving, and the process of carving, connected me to something. What this was, I wasn’t sure. But I had felt a subtle electricity in my veins, the echo of a distant and unquenchable spring.”

His approach to writing has been similar to his approach to stonemasonry, or archaeology before that. Before he started to write he wanted to learn how to do it, and had taken a course on creative writing. He says writing is like other craft skills and needs to be learnt and honed. And, just as with stonemasonry, the learning never ends. There is always something new to be discovered, explored and developed.

He had written two books, a heritage guide and a book about Exeter Cathedral, before starting King of Dust. “I had been wanting to write a book about Romanesque work in the South West for many years,” he says, “but I didn’t want it to be academic.”

He had already started the book when he presented the idea of it to the publisher, Little Toller Books. Approaching the publisher came about in a roundabout way. He had been approached by them after he had written a review of another book they had published. They asked him if he might write a book for them. One day when he was looking for a church at Toller Fratrum in Dorset he got lost and found himself at the premises of Little Toller Books (although they have since moved). He went in to say hello and ask the way to the church. The relationship grew and in due course Little Toller Books published King of Dust.

Alex found the church at Toller Fratrum and his painting of its Romanesque font is reproduced above. It is also included in the book. He writes about the font in a chapter called ‘In Zigzag Shadow’, a description that refers particularly to the west portal of a priory in the Cornish village of St Germans (the name comes from St Germanus of Auxerre who visited Britain in 429AD).

Hands across time

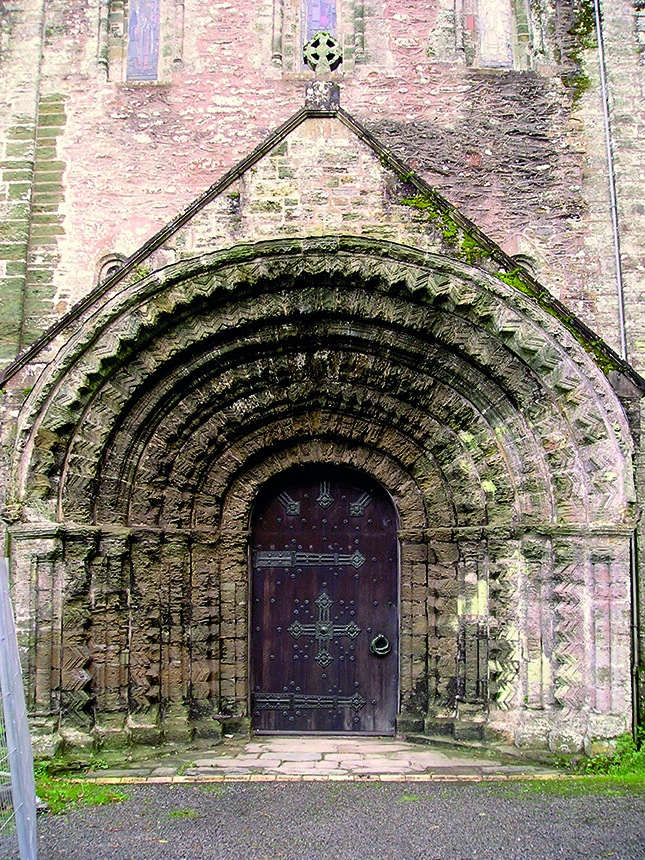

Alex writes of his visit to St Germans Priory: “As I walked down the gentle hairpin road to the entrance I felt like I was trespassing. I’d come to see the west portal, a gaping mouth of a doorway, composed of seven successively smaller arches (or ‘orders’) deep and animated by rows of zigzags. It seemed suitably overwhelming, particularly with a low, grey sky pressing an unexpected darkness into the stone, a coarse volcanic from Tartan Down near Landrake which varied in colour from deep green to mid-brown. The carving was flaky, friable and much had been lost. In places only the outlines of ghost chevrons meandered across raw lumps of stone; in others strong sharp points remained. It was a gap-toothed smile, ragged with age.”

King of Dust is Alex’s journey to a hands-on understanding of the Romanesque carvings he seeks out, as well as a connection with his medieval counterparts, his own life reflecting theirs through the stone, the tools and the skill in using them that he has acquired.

And the tools are important to him. Alex writes in the chapter called ‘Honeychurch Twilight’ that they “can assume mystical properties, crucial as they are to this transfer of energy from inside to outside, from the interior images circulating around your head to the stone itself”.

In the same chapter he talks about being given a chisel he particularly liked by another mason. “Travelling light, I hadn’t taken my tools with me; besides, Tom had assured me I could use his. One in particular came alive as I used it, a two-inch claw chisel that sped up an onerous job of trimming away waste stone on the Dorset greensand. I connected with it almost instantly. It was well-balanced and beautifully made, the shoulders of the chisel angled like a faceted jewel. With each use it felt more and more natural. Tom felt no such attachment, though, so he gave it to me and I bought him a new one.”

In his studies, Alex has clearly read a lot of books, which he references throughout King of Dust, empathising with the writers and artists similarly drawn to architecture and carvings expressed in stone as the book meditates on craft, the importance of the hand-eye-brain connection in the creation of art and the transformative power of art in human lives.

Art on the internet

After his training at Weymouth College, Alex went to work at Exeter Cathedral, where he was a stonemason for six years.

He was brought up in Sussex, where tumble-down buildings, skateboarding and Gothic bands such as Sisters of Mercy, Bauhaus and Fields of Nephilim combined to give him a fascination and love of medieval architecture and archaeology in the first place.

He is back in Sussex now, writing, painting, teaching the architectural history module for the Cathedral Workshop Fellowship and occasionally helping out on masonry projects. He has also turned his attention during the pandemic to his website (www.alexwoodcock.co.uk), which includes a new e-commerce section where he sells his book and his drawings (and prints of them), some of which have been used as illustrations in King of Dust.

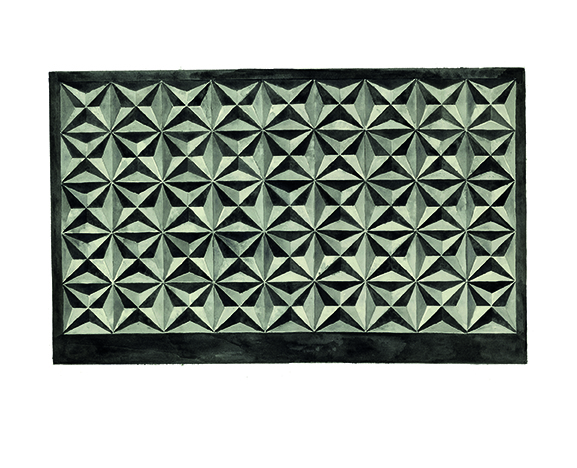

Some of the Romanesque carvings he has drawn in pen and wash might look naive, like the carvings themselves, but their simple lines are hard to perfect. Ornate work, both in drawing and carving, is often easier because ornamentation can hide bad workmanship that unadorned work will expose. People also seem to like the naive, as well as the repeating patterns of the Romanesque. Alex’s Votive Stone painting (pictured here) has been particularly popular. Perhaps it evokes the visual equivalent of an autonomous sensory meridian response.

“Drawing is something I have always done since I was an archaeologist,” says Alex. “It was also encouraged at Weymouth. During the pandemic I thought maybe selling my drawings on my website could be another string to my bow. There’s a whole world of people who love buildings and heritage."

Little Toller is an independent publisher of books about nature and place. It is now based in Beaminster, Dorset, but was previously at Toller Fratrum, from which its name derives, just a few yards from the chapel of St Basil’s, which boasts the Romanesque font painted by Alex Woodcock. The font also forms the publisher’s logo (pictured right). www.littletoller.co.uk

Little Toller is an independent publisher of books about nature and place. It is now based in Beaminster, Dorset, but was previously at Toller Fratrum, from which its name derives, just a few yards from the chapel of St Basil’s, which boasts the Romanesque font painted by Alex Woodcock. The font also forms the publisher’s logo (pictured right). www.littletoller.co.uk

Below. The Romanesque west portal of the Priory in the Cornish village of St Germans pictured in King of Dust, where Alex describes it as a suitably overwhelming “gap-toothed smile, ragged with age”.