Chris Wood spent his last day as Senior Building Conservation Advisor with Historic England speaking at the Traditional Roofs conference held in Church House at Westminster Abbey, London, just before the coronavirus lockdown. The following day he retired after four decades in the heritage sector, the last 25 with Historic England / English Heritage, where he was Head of the Building Conservation & Research Team. Here he looks back on that career.

My work on historic buildings has covered a diverse range of materials, arguably the most important of which is stone. My involvement has ranged from advising on detailed repairs to commissioning and carrying out research and campaigns, teaching, on-site conservation and generally promoting the use of appropriate, mainly local stone for use on heritage projects. Much time was also spent on encouraging the re-opening of historic delves and quarries, with all the attendant benefits of sustainability, local employment and rejuvenation of skills.

There are many materials used on historic buildings, all of them important and interesting, but none more so than stone. Landscapes in the UK are varied and distinctive. Much of this is due to geological events over millions of years that generated the rock producing the stone used for building. People are passionate about such distinctiveness yet when objecting to the re-opening or extension of a quarry conveniently ignore the fact that what they enjoy so much was won locally from the ground.

Working with luminaries in the stone sector, particularly over the past 25 years with Historic England (and English Heritage before it split into the two entities) has been illuminating and a pleasure in equal measure. They have included geologists, academics, scientists, stonemasons, slaters, conservators, quarrymen... too many to name individually in this short article.

Early days

Early inspiration when working as a conservation officer in a rural part of Hampshire came from the writings of Ruskin, Donovan Purcell, Alec Clifton Taylor, the teachings of John Ashurst (later to become a working colleague) and visits to John Bysouth’s stonemasonry yard in Tottenham, where excellent advice was generously given.

Rural East Hampshire was not noted for its stone heritage, but good early lessons were provided, dealing with the local ‘malmstone’, which is similar to clunch.

If this stone was repointed with cement mortars or an alien (usually more dense) alternative stone used for repairs, deterioration of the old stone was rapid. But if treated correctly it performs well.

Other local stones are the extremely robust flint and ironstone, as well as the honey-coloured Bargate sandstone. These stones provide a wonderful visual contrast and demonstrate the vital importance of local stone to the distinctive charm of this part of England, even though it is an area more noted for its timber framing, brick and tiled buildings.

Research and campaigns

Commissioning and carrying out research to try to answer problems related to repairing stones has long been an important part of the role of Historic England (and its predecessor).

Some projects have been confined to a better understanding of the stone itself, others to investigating the performance of solutions, such as the use of consolidants, different mortar compositions, cathodic protection, soft capping... and more.

Improving production techniques is not normally associated with public bodies like Historic England but, nonetheless, funding the research to develop an artificial method of frosting stone slates has helped to establish a supply of new Collyweston roofing (see Figure 1) after many years.

Fig 1. David Jefferson and Terry Hughes at Apethorpe Hall during the trials to establish a method for artificially frosting Collyweston slates, which is necessary to allow the stone to be split. These slates had not been commercially available for years, partly because winter frosts were unpredictable and becoming rarer. The eventual success of this research enabled a new supply of Collyweston slates for the first time in decades. This has also stimulated others to produce Collyweston slates and now Claude Smith & Sons in Stamford have re-opened an old mine to supply the stone.

Fig 1. David Jefferson and Terry Hughes at Apethorpe Hall during the trials to establish a method for artificially frosting Collyweston slates, which is necessary to allow the stone to be split. These slates had not been commercially available for years, partly because winter frosts were unpredictable and becoming rarer. The eventual success of this research enabled a new supply of Collyweston slates for the first time in decades. This has also stimulated others to produce Collyweston slates and now Claude Smith & Sons in Stamford have re-opened an old mine to supply the stone.

Strategic Stone Study

The largest research project undertaken (in terms of scale and cost) is the Strategic Stone study, soon to be re-launched as the Building Stone Database for England.

The research is virtually completed and has employed geologists from each county working with the British Geological Survey (BGS – the geological equivalent of the Ordnance Survey) to map all known historic quarries and the stones they produced, as well as a token range of historic buildings constructed of the stones on to a freely accessible interactive GIS (Geographic Information System) map (see bit.ly/buildingstone).

More recently Gekoella Ltd (geologists and environmental consultants under the direction of Andy King) have been completing the last few counties. So far, around 3,700 distinctive stone types have been identified.

The original aim of the study was to provide these data for Mineral Planning Authorities in order for them to use the information to safeguard important sources of historic stone. The maps and other information about the stones, together with freely available gazetteers for each county, have also proved useful to schools and other groups.

The genesis for the project arose from two sources. Graham Lott of the BGS posed the idea to me when I was manning an English Heritage exhibition stand back in 1997. Graham became an invaluable aid to the project, even after he retired, and was always extremely generous with his profound knowledge¹.

At the time, the sheer scale and cost of the task was beyond English Heritage, although other events conspired to bring it to fruition six years later.

A particularly acrimonious planning battle over re-opening a small stone slate quarry in West Yorkshire, which had arguably been the most important source of stone slates in England, had ended with permission being refused after the fourth time of being considered by the Peak District National Park Planning Board.

Unfortunately, the site was just inside the National Park. English Heritage had strongly supported the applicant. The only positive outcome was that the central government Department for Communities & Local Government (DCLG) commissioned the Symonds Group to review the issue of safeguarding important mineral reserves, particularly for building and roofing stone.

Symonds concluded in their report Planning for the Supply of Natural Building and Roofing Stone in England & Wales, which was published in 2003 (and is often more succinctly referred to as ‘the Symonds Report’) that ‘heritage quarries’ should be safeguarded from being sterilised and that English Heritage should establish a database for Mineral Planning Authorities to determine which were the important sites that merited safeguarding.

This provided the impetus to set up the Strategic Stone Study. The problem was, how was it to be done.

A one-year pilot study investigating the white sandstones of the West Midlands was devised. I was working on this with two of our eminent consultants, Terry Hughes (slating specialist) and David Jefferson (geologist), along with allies at the Building Research Establishment (BRE), notably Tim Yates, and Graham Lott1 and Don Cameron at the BGS.

This established the method for starting the Strategic Stone Study, although it would not have got off the ground without two substantial grants from DCLG. Securing those grants owed much to the support of Brian Marker and his colleagues in the Mineral Planning Division.

Proactive support for opening or re-opening quarries and delves has continued. English Heritage has long needed the correct stone for repairing the monuments in its care and this has usually meant finding the original source.

Roofs of England

This need was highlighted during the ‘Roofs of England’ campaign run by English Heritage. Its aim was to try to rejuvenate stone slating in England and carry out much needed research. Terry Hughes managed the project and I travelled with him to all the slate producing regions, visiting delves, quarries and roofing projects.

The campaign identified more than 40 distinctive stone slate types used in England, although by the 1990s only two were still in production (anyone interested in learning more about stone roofing should visit Terry website at www.stoneroof.org.uk/cnts.html).

New stone was essential if buildings were to be properly conserved. Without it, old roofs were either cannibalised for their valuable second-hand slates or had the slates stolen. Inappropriate imported slates or concrete substitutes were commonly used instead. Support in principle was therefore given to

re-opening or extending old quarries, provided it would not cause other insurmountable environmental problems.

Research carried out during the campaign showed clearly that small quarry operators were existing at the margins of profitability and it was often essential that they be allowed to sell ancillary products, such as walling, copings and other stone products, if they were to remain viable.

Support given to small operators saw quarries opened in Shropshire and Herefordshire, mainly supplying sandstone slates. Training was provided to farmers and prospective producers in winning and dressing the slates to provide traditional finishes.

During the campaign I found myself having to assume responsibility for a quarry operation – an unusual situation for someone working in a normally risk averse organisation.

It came about as a result of the nave roof of St Michael’s and All Angels Church in Pitchford, Shropshire, needing to be re-roofed because the Harnage sandstone slates had begun to sag dramatically. You can read more about that in an English Heritage Research Transactions report that can be downloaded as a PDF from bit.ly/stoneroofs.

The parishioners wanted to replace the stone slates with machine-made clay tiles. This was resisted by English Heritage – and as it was meeting most of the costs of the project it was agreed that a source of Harnage stone should be found.

Limited funds

A limited amount of money was made available for the quarrying as part of the grant. The most suitable site was found, trials of fissile stone were carried out and planning permission obtained. A mobile quarry operator was selected and he and his team would win the stone and rive it (split it) on site before transporting it back to their premises in Wiltshire for the slates to be dressed under cover.

All seemed fine although, unfortunately, only enough money was available for four weeks of quarrying – and the first week was spent trying to find splitable stone.

The quarry was at the top of a hill. That November turned out to be the wettest on record, making access and working difficult. It was all rather tense as hasty decisions had to be made that could either succeed or scupper the whole project.

Fortunately, it all worked well and it proved to be a beneficial insight into the precarious nature of small-scale stone production.

It’s not just small producers that were supported, however. Gallaghers’ application to extend its essentially large-scale aggregate-producing Kentish Rag quarry was extremely controversial because part of the site included ancient woodland.

Although my letter of support merely set out the importance of the stone for the South East of England and the need for a reliable supply for repairs, leaving other considerations to the County Council, it did not stop a volley of vitriolic hate-mail from individuals, none of whom actually lived anywhere near Kent. Gallagher increased its dimensional stone business so the stone could be supplied for heritage work as well as new build and obtained planning permission for the extension.

Training

Managing and contributing to training courses offered at the English Heritage bespoke training centre at Fort Brockhurst in Gosport, Hampshire, in the 1990s was onerous but extremely rewarding.

Most of the early courses were a week long and covered masonry conservation by way of lectures and demonstrations, with hands-on work on purpose-made indoor ruins.

I was fortunate enough to be working alongside Colin Burns, a seasoned, time-served stonemason with many years’ experience working on English Heritage monuments, and the late John Ashurst, with whom he had worked for much of that time.

John is still a major figure in building conservation, particularly through the many seminal publications on stone conservation he authored and co-authored.

A most enlightening project with both of them was to carry out condition surveys of many of the ruined abbeys, castles and monuments in the care of English Heritage. Much was learned from masons who had carried out innovative repairs going back to the early 1960s.

Although originally aimed at the English Heritage ‘in-house’ work staff, the Fort Brockhurst courses were adapted to suit a wider range of professionals and contractors who eventually formed the bulk of the audience.

Sadly, the training centre was closed after five years because of cut-backs, but rather than let everything quietly disappear, David Leigh, then Director of West Dean College in Sussex, agreed to accommodate all the training facility, including what had become known as the ‘ruinettes’, and take on the teaching staff to run the Masterclasses at West Dean.

There was no funding for the move, so I, Colin Burns and others who were on gardening leave dismantled all the walls and ruins, stone by stone, labelling each one for the trip by low loaders to Sussex in order to re-assemble them just as they had been at Fort Brockhurst.

The courses at West Dean have been expanded over subsequent years and continue to this day, with several hundred people having now attended them.

An important aspect of practical training is the provision of on-site demonstrations of best practice techniques, usually for the benefit of architects / surveyors and contractors faced with problems or experiencing a building material failure of some kind. One notable example was at Liverpool’s Anglican Cathedral, a most imposing piece of early 20th century

stone-faced architecture by Giles Gilbert Scott. Local masons had produced a rather unsightly attempt at repointing fairly wide and prominent joints. Their work was damaging the locally sourced soft red sandstone.

So the exercise carried out with Colin Burns was primarily one of demonstrating good practice with the use of appropriate tools, materials and techniques. It was also useful for research and testing purposes, as a relatively new, highly marketed hydraulic lime was being asked to perform on a particularly hostile site.

A demonstration area was chosen on a turret more than 200ft (61m) from ground level facing the Irish Sea. Although well protected initially, the finished work would be subject to strong winds and driving rain.

Preparing the demonstration area and producing the model joints took a good 12 hours, eventually finishing at 9-o-clock at night, long after everyone else had gone home. But it proved to be a successful training exercise and sound test of the repair technique and selected mortar. When the joints were inspected two years later they were still in good condition.

On-going

Many of the questions about stone that research undertaken by Historic England has attempted to answer are difficult. Indeed, some cannot be satisfactorily resolved. This is partly because of the varied properties of the particular stones in question and partly because it is important to ensure that remedial treatments do not cause more damage than they prevent, and that they continue to perform well over time.

One of the unique opportunities of working for Historic England on materials research is that it offered a rare opportunity to revisit tests, trials and completed work over several decades. This is important if the effects of repairs and treatments are to be assessed over the sort of time period (a minimum of 25 years) that it is hoped they will benefit historic buildings, particularly when the work is publicly funded.

Much time and thought, backed by research and testing, has been spent on a number of stones termed ‘hard to treat’.

For example: Magnesian limestone; Clunch (Figure 2); Reigate stone; Polyphant (Figure 3); Lower Lias; Septaria and Purbeck marble.

Some exhibit mechanisms of failure that are so dramatic they cause the sudden disintegration of what can be important structural masonry.

Insipient polluted moisture can precipitate a reaction in Magnesian limestone by forming particularly soluble magnesium-sulphate salts that can turn stone to powder, resulting in catastrophic failure.

This is one reason why virtually all external masonry on York Minster has been replaced. But this does not happen with all Magnesian limestones. Neighbouring stones can remain unaffected and it is difficult to predict when the change will occur.

There is a similar type of problem with Polyphant in Cornwall. The stone includes aluminium and magnesium silicate (talc) and its layered structure makes it susceptible to water absorption, leading to expansion, cracking and surface lamination. Conservation is especially difficult as the talc prevents adhesion of any applied material. St Paul’s Church in Truro, although looking sound from the outside to most people, is beyond economic repair as a result of this.

All of this work is continuing at Historic England with my successors being ably assisted by conservation consultant David Odgers, who has carried out many of the field trials.

As well as helping to open quarries, Historic England has and is working hard to support the use of indigenous stone in a wider capacity.

It has consistently supported the cause by exhibiting every two years at the Natural Stone Show at ExCeL in London, even during various economic depressions when most of the other exhibitors came from overseas. My former team continue to organise and run the popular and well-attended Conservation Conference on the final day of the exhibition, with the sizeable audience the conference attracts also benefiting those exhibiting.

English Stone Forum

Similar motives spurred me and several of the people mentioned above to establish the English Stone Forum in 2006, ostensibly to support initiatives seeking to increase the awareness and value of indigenous stone.

From a launch at The House of Commons and an opening conference in York, the Forum draws representatives from industry, the professions, local authorities and academia and is there to provide expert and independent help to those with an interest in sourcing and winning local stone. It has supported several ultimately successful quarry planning applications.

A good relationship exists between Historic England and Stone Federation Great Britain and discussions are on-going with the Stone Federation so the benefits of membership can be made available for small, heritage stone producers at a cost that reflects their limited means. Ex-colleagues continue to maintain and enhance links with the Federation by providing training for its members on stone heritage training days.

Links such as these are vital if the benefits of the research and advisory work undertaken by Historic England are to reach their intended audiences. And championing the use of much-needed local stone to repair and enhance the UK’s unique and diverse stone heritage must remain one of the most important objectives of building conservation.

- Sadly, Graham Lott passed away in July this year.

- Chris will report on some specific aspects of his research into working with stone in future editions of Natural Stone Specialist.

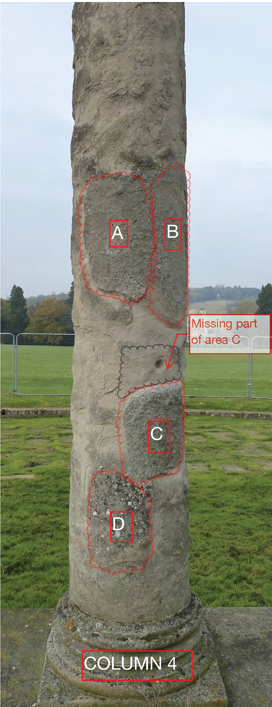

Fig 2. Three aspects of Audley End, Essex, showing panels of trial finishes and decay on the columns of the Temple of Concord, which is in the grounds. Clunch has long been regarded as an inferior building stone. However, a great many important historic buildings have been constructed with it, some of which are now listed at Grade 1. Trials at Audley End, carried out by David Odgers and Colin Burns, indicated that a weak lime-based shelter coat can effectively reduce the incidences of pore-blocking, which is one of main causes of failure of Clunch.

This pictures show trials carried out in the 1970s to the columns at The Temple of Concord to test a variety of treatments aimed at slowing the decay of the clunch. It is interesting to note that Brethane, a consolidant devised by Cliff Price and John Ashurst, is still in good condition and seemingly protecting the Clunch around it. Further trials are planned.

This pictures show trials carried out in the 1970s to the columns at The Temple of Concord to test a variety of treatments aimed at slowing the decay of the clunch. It is interesting to note that Brethane, a consolidant devised by Cliff Price and John Ashurst, is still in good condition and seemingly protecting the Clunch around it. Further trials are planned.

Fig 3. St Paul’s Church in Truro is Grade II listed but not now being used for worship. It was built in the 19th century using Polyphant stone, which was widely used in medieval times but only for indoor work. Once the stone gets moist it can decay quickly