As the stone restoration work on the Elizabeth Tower (what many people call Big Ben) at the Houses of Parliament reaches its conclusion, Rory Smith, the Stonemasonry Foreman of DBR Ltd (which is currently celebrating 30 years in business) talks about the work carried out.

Most people reading this will be familiar with the Elizabeth Tower, the clock tower of the Houses of Parliament. Some people refer to it as Big Ben, although that is actually the name of the 13.7-tonne bell that strikes the hours. The Clock Tower was constructed as part of Charles Barry’s rebuilding of the Palace of Westminster after the old palace was devastated by a fire in 1834. It is constructed of 850m3 of Anston stone from Yorkshire, Clipsham stone from Rutland and Caen stone from France, which covers 2,600m3 of brick.

Elizabeth Tower is a central feature of the Parliamentary Estate and this national icon is undergoing major restoration work that, in my capacity as DBR’s Stonemasonry Foreman on the project, I have been fortunate enough to witness first-hand.

Due for completion next year (2022), this unique structure presents a whole host of challenges for traditional stonework, particularly operating within relatively confined spaces and at high elevations.

However, the nature of the work, particularly some of the fine detailing, serves as a fantastic showcase for the skill, precision, and artistry of this time-honoured profession.

Here I want to take the opportunity to give Natural Stone Specialist readers a guided tour over the work DBR has undertaken and delivered on this exciting project. I will also explore some of the specifics around the stonework itself, and why this conservation project should serve as a platform to encourage more young people into the profession.

Monumental Challenge

Although Barry oversaw the rebuilding of the palace after the 1834 fire, what became the Elizabeth Tower was designed by renowned architect Augustus Pugin in a Neo-Gothic style. It was completed in 1859. Standing 315ft tall, as measured in those days (96m), it has always occupied a prominent position in the London cityscape. But, alas, after 160 years of wear and tear, including bomb and weather damage, essential repairs were needed to return the structure to its original splendour.

Unusually the tower was built from the interior outwards, without an external scaffold. Granted, it’s a clever and efficient construction method but it doesn’t lend itself to modern conservation work.

Along with repairing significant areas of damage from World War II, there have been several other conservation projects carried out to Elizabeth Tower over its lifetime. Examples of palliative repairs could be found across the entire building and a large amount of Clipsham Stone indents are spread over the Tower.

Some of these repairs were failing by the time we arrived on site. Many more, particularly the Clipsham work, had not aged well, and while they were structurally sound, they were far from sympathetic to the building as a whole.

Working round the clock

In 2017 DBR was brought on to the project by principal contractor Sir Robert McAlpine and, with the entire building requiring restoration, the company’s stonemasons, stone cleaners and conservation specialists knew they had their work cut out to deliver a project with such an extensive and sensitive range of masonry needs.

The scope of work ranged from delicate indents through to full stone replacements; from new cantilever stairs treads to finely carved panels. Not to mention a replacement floor to the belfry, where we had to lay over a hundred slabs of Hopton Wood limestone weighing up to 110kg each without hitting our heads on the various rather large bells that make the space so special. The bells were, of course, silenced while we carried out the work or we would have been deafened.

The damage we found was largely typical for a building over 150 years old. A lot of very fine work has been considerably eroded, although we were only able to see this once the scaffolding was up and we were able to get up close.

The project started off with in the region of 250-300 indents. That rapidly increased to 900-1,000 indents as we surveyed the full extent of the deterioration and disrepair.

The effects of rain, cold weather, salt and pollution had all taken their toll. Issues such as delamination, cracked pointing and heavy carbonation were common across the whole façade.

We knew it would present a massive test of skill and expertise for our on-site team.

Addressing inconsistencies

One of the most obvious inconsistencies resulting from previous restoration was discovered when we went through the process of identifying the type of stone to be used for the conservation work.

From archive records we knew the original material was Anston Stone, a sandy coloured limestone from a quarry in the village of Anston in South Yorkshire. Unfortunately, as a large housing estate now sits over the original quarry site, it is impossible to get any more stone from that site.

Restorations in the 1980s had used Clipsham, however, there’s a tonal contrast between this and the original Anston. Furthermore, the texture and the effects of age also differ significantly.

As such, when DBR started on The Elizabeth Tower, we were committed to using a stone as close to the original Anston as possible. Returning to the North Derbyshire / South Yorkshire area, we were able to follow the same geological seam until we found a suitable quarry with a similarly profiled stone: Cadeby, specifically Cadeby bed one.

The quarry is near Doncaster, South Yorkshire. The stone there has been quarried for hundreds of years. It is a fine and consistent limestone that can hold a sharp crisp arris and fine detailing for masonry work. The bed height available meant that, with only a few exceptions, we were able to work details to the original dimensions.

DBR and the project design team would regularly visit the Cadeby quarry to select the best-looking stone. The chosen blocks were then sawn six sides and sent from Yorkshire to the site in Westminster.

Of course, before we do any working, we record every part of the project, down to the minutest piece of detailing. From there we draw to a one-to-one scale and create plastic templates to work the stone to size.

On The Elizabeth Tower, each and every bit of the restoration is unique. You are not looking to create identikit pieces, so hand finishing is essential. We still work with predominantly traditional methods, mostly using mallets and chisels. The extensive amount of ornate and decorative stone, a signature of the Elizabeth Tower’s Neo-Gothic vernacular, required a degree of finesse and a delicate touch.

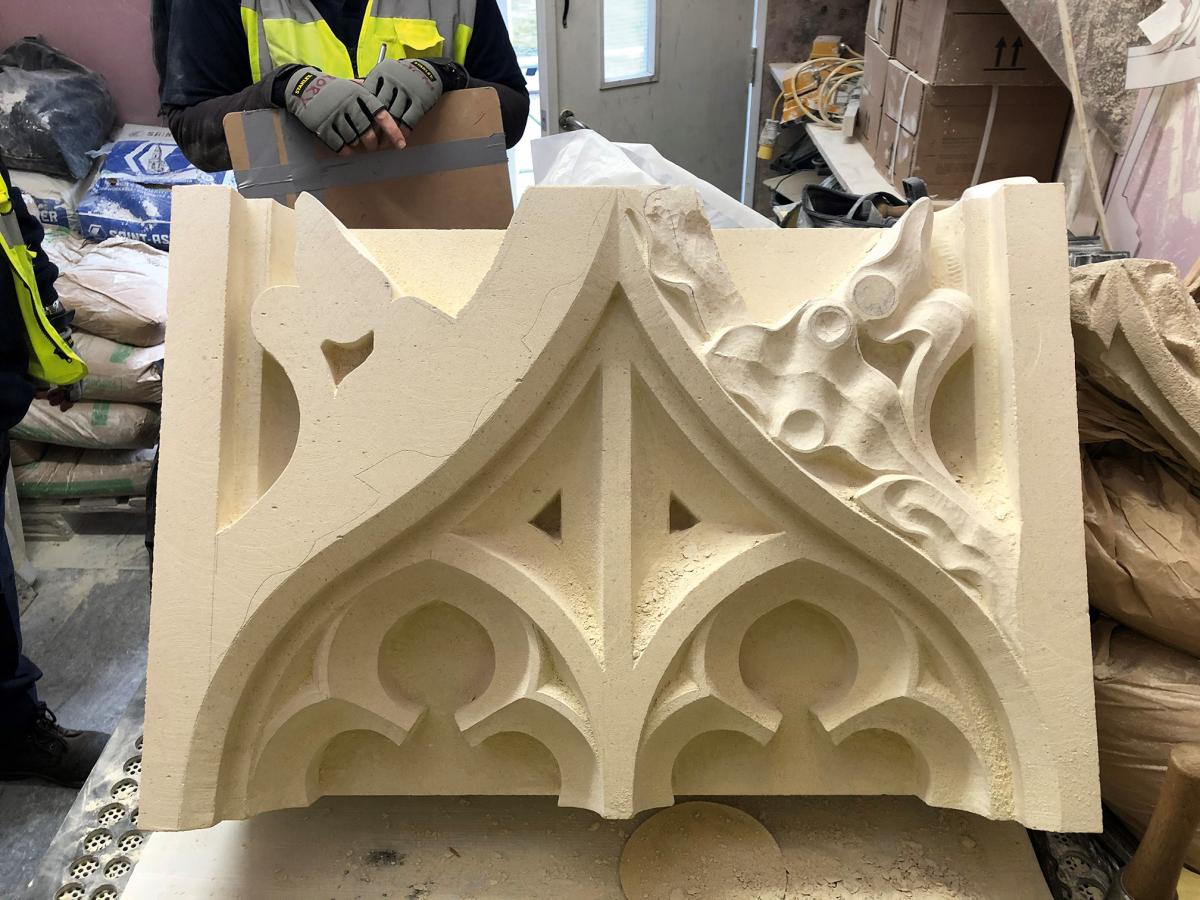

Some of the panel work and tracery produced for the repairs to Elizabeth Tower. What had originally been expected to be 250 indents turned out to be about 1,000.

Some of the stones required high levels of detailing and advanced masonry techniques, all worked on site in the banker shop set up there by DBR. On some of the stones, such as the example below, weeks, if not months, worth of work has gone into them.

Of course, it is then about getting the stone to its allocated spot, not an easy task when working hundreds of feet up on a narrow scaffold.

For the smaller stones, we manhandle them in. For the bigger stones we use block and tackle to hoist them into position.

We then secure them, bedded on a natural lime mortar and secured with mechanical fixings, such as stainless steel dowels and resin. They are then grouted and pointed.

Finally, ahead of architectural sign-off, the masons in the banker shop come up to the scaffold and dress their stones in situ, getting the last couple of millimetres trimmed, chiselled and rubbed down so they align perfectly.

We’ve almost finished on site, with the final touches and checks to our work being undertaken. The fact that this has been delivered to deadline is a testament to the experience of our team.

I also feel that the work on the Elizabeth Tower truly showcases the breadth of the stonemasons’ craft, as well as how the ancient skills practiced by stonemasons still maintain relevance and purpose in modern society.

The Year of the Master Craftsperson

Currently, the profession is at a crossroads. While we have enough hands to deal with current levels of work, there’s an expectation the number of projects coming online will spike over the next decade. With specialist skills shortages exacerbated by world events and a lack of home-grown talent coming into the industry, we potentially face a squeeze on skilled resources.

DBR Ltd, is looking to work with industry bodies, including Stone Federation Great Britain, on a skills and talent focused campaign being called ‘The Year of the Master Craftsperson’.

Launching in the new year, this campaign will address the looming skills shortage head-on and help to preserve our unique social role, so that we can continue to conserve our heritage buildings for future generations.

As it gains more awareness, I hope the work we have carried out on the Elizabeth Tower both educates and inspires others to consider a career in this rewarding profession that is hugely important in retaining the built heritage of the nation.

Below. A major contribution to the restoration of the tower has been the analysis of the paint originally used on and around the clock face and the repainting and reguilding of metalwork and stone by Cliveden Conservation. Analysis of original paint flecks was undertaken by Lincoln Conservation at Lincoln University to ascertain the colour scheme and was used to transform the clock from the black of recent painting regimes to the original bright, colourful scheme envisaged by Charles Barry in 1834.

Picture: ©UK Parliament – Jessica Taylor