Photo: John Stewart

Apart from the occasional Banksy, graffiti is not usually welcome on any building, but removing all trace of it can be difficult, especially from historic buildings when it’s important to retain the patina of age on the fabric under the daubing. Historic England offers some guidance.

Graffiti is not new. Bored Roman soldiers scratched their sometimes rude messages into the stones of Hadrian’s Wall and young Issac Newton left sketches and notes on the walls of his parents’ home of Woolsthorpe Manor in Lincolnshire. They are now considered an important aspect of the fabric of those historic structures.

And when Banksy or New York’s Jean-Michel Basquiat decide to leave graffiti, the walls they paint can end up more valuable than the buildings they are part of.

It is an interesting point that does not go unobserved in the new technical advice document on graffiti from Historic England.

The publication is called Graffiti on Historic Buildings – Removal and Prevention, which replaces Graffiti on Historic Buildings and Monuments – Methods of Removal and Prevention published in 1999.

The 66-page Graffiti on Historic Buildings – Removal and Prevention can be downloaded free from bit.ly/TAgraffiti.

It is true that removing graffiti might be destroying the work of somebody who proves to be a genius, or could perhaps contain a sentiment that could prove socially significant, like the work of conscientious objectors of the World Wars, but people can generally distinguish between ‘street art’ (sometimes called ‘graffiti art’) and the lesser daubings of those seeking a public canvass for their ego or angst.

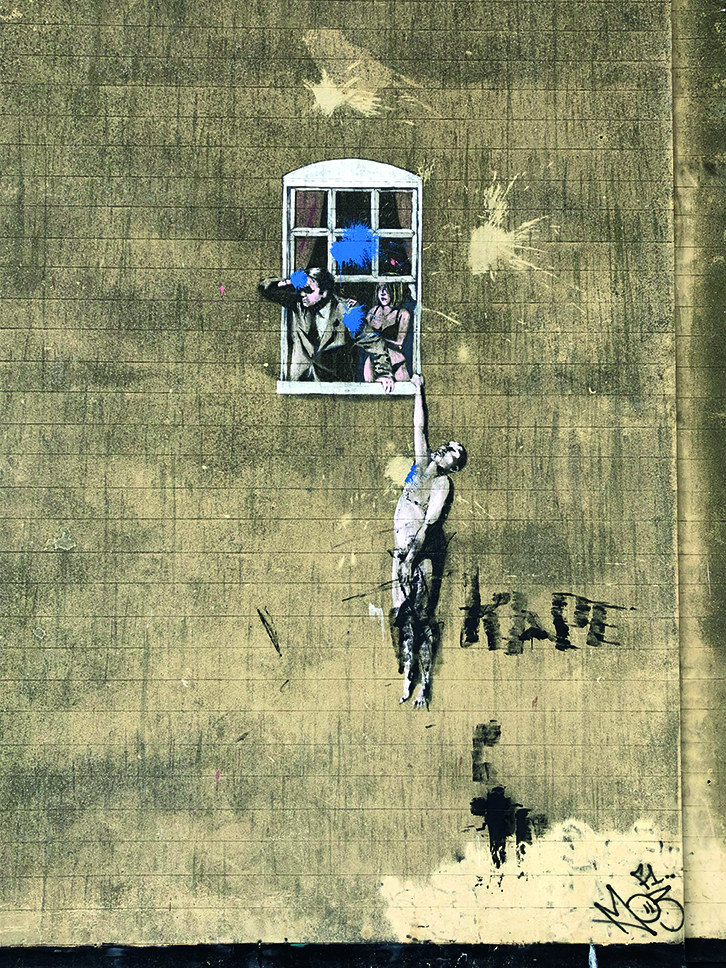

Banksy’s Well Hung Lover (2006) in Bristol is among his best-known works. It gained public acclaim and press attention, both on its completion and in response to its subsequent defacement by other graffiti. Photo: Catherine Woolfitts.

Banksy’s Well Hung Lover (2006) in Bristol is among his best-known works. It gained public acclaim and press attention, both on its completion and in response to its subsequent defacement by other graffiti. Photo: Catherine Woolfitts.

In the new Historic England publication the point is made that whatever the artistic merits of graffiti or 'street art' might be, it is often there illegally.

Painting of buildings might be controlled through an Article 4 direction, where certain development rights are removed by a local authority to help preserve the character and appearance of an area. This is not automatic but something that can be applied to a specific conservation area.

For a listed building, consent will probably be required if anyone wants to add some kind of mural, and for a scheduled monument consent will always be required.

Where street art is proposed, it is advisable to check what permission is needed with the local planning authority.

And regardless of whether the owner of the building has given permission or not, local authorities have the power to remove unauthorised street art.

Most of the graffiti added these days is not considered an enhancement, especially when it is daubed on historic buildings where it is considered important to preserve them as near as possible to their condition at some point in the past.

Clara Willett, Senior Architectural Conservator with the Building Conservation & Research Team at Historic England, oversaw the production of the new Graffiti on Historic Buildings technical advice note. It was written by Catherine Woolfitt, an archaeologist and architectural conservator who is Subject Leader of Historic Building Conservation & Repair at West Dean College, and Jamie Fairchild, a Director of cleaning products company Restorative Techniques, who is often consulted when graffiti needs removing.

The three of them presented a 90-minute webinar as part of Historic England’s ‘Technical Tuesday’ series last year. You can still watch it at bit.ly/HEgraffiti.

Clara Willett explains why the new publication on graffiti was needed now: “Graffiti rarely enhances the surface it’s applied to; not only is it illegal to mark a structure without the owner’s permission, but it usually disfigures its appearance.

“Graffiti can particularly affect the value of a heritage asset and its setting.

“Although lead theft has been found to be one of the most destructive heritage crimes, vandalism, which includes graffiti, is the most common.

“During the pandemic lockdown of 2020 there was an increase in graffiti – a combination of boredom, frustration and opportunity.

“Graffiti removal requires resources and if done inappropriately can cause further damage.

“The recently published technical advice note on removing and preventing graffiti brings together best practice guidance on removing graffiti sensitively from historic structures as well as options for preventing it.

“It outlines how to respond to a graffiti incident and stresses the importance of approaching its removal methodically, using appropriate methods.

“There is a wide variety of techniques and chemicals which can be highly effective in capable and experienced hands.

“Some simple measures such as strategic landscaping and planting can make surfaces less accessible, which can help prevent graffiti incidents.

“Anti-graffiti coatings can offer some protection, although they can detrimentally affect the appearance.

“This guidance offers practical help which is useful to public and private building owners.”

Graffiti on Historic Buildings – Removal and Prevention provides useful, practical guidance to building owners, conservation professionals, local authorities and estate managers responsible for historic buildings and sites.

It describes the types of graffiti and historic materials affected, the legal context for reporting and prosecuting graffiti crime, general advice on removing graffiti, best technical practice expected of specialist graffiti-removal contractors, and prevention measures.

A major point to take from the publication is that there is not one, simple solution, either to avoid graffiti or to remove it.

A lot of different materials are used by people who want to leave their mark, from lipstick and marker pens to food colouring and spray paints. What is used makes a difference to how it can be removed. And the building material they have been used on makes a significant difference to how they can be removed as well.

An interesting observation in the publication is that graffiti left on walls and statues as part of the Black Lives Matter and Extinction Rebellion demonstrations last year was sometimes food colouring, possibly because those using it thought it would be environmentally friendly.

It is speculation, of course, but possibly the people using food colouring to produce graffiti might also have been thinking it would be easy to wash off. On some surfaces it is. But on stone, which is porous, and some historic brick and render, it can actually be harder to clean off than spray paint because it is water-based and penetrates deeper into the historic fabric of the wall. It can require repeated poulticing to draw it out.

Apparently, Extinction Rebellion protesters had an old fire engine filled with food dye that they intended to spray on the Portland limestone of the Bank of England in Threadneedle Street, London, which would have presented an interesting cleaning job for someone. The food dye was never sprayed because the fire engine broke down on the way.

Jamie Fairchild says one of the materials used in a graffiti attack on long barrows recently seems to be face powder.

At Restorative Techniques, part of the consultancy service has always involved analysing materials and a new laboratory is now nearing completion. “That will help push along the research side, as well as making long-term testing easier and analysing paint samples. Because there are a number of cleaning issues that have not yet been resolved. You think: there has to be a better way of doing this.”

The social and historical aspects of graffiti are largely the province of Catherine Woolfitt in the new technical advice note, while the nitty-gritty of graffiti identification and removal is dealt with by Jamie Fairchild.

He tells NSS his company has been busy, and the level of activity has only increased so far this year, with graffiti part of the reason.

“We get regular graffiti work,” he says. Some of it is with English Heritage, which remained responsible for 400 or so historic properties and sites following the splitting off of Historic England as consultants and government advisors in 2015.

Jamie says while other materials are encountered, notably food dyes lately, most of the graffiti he is asked to deal with involves aerosol spray can paints for car bodies and hobby paints.

An issue with removing graffiti is that it can leave the area cleaned looking brighter than the rest of the building. Superheated water cleaning, for example, will remove any biological growth, so if a wall has the green tinge of algal growth, superheated water and many cleaning chemicals will kill it. As a result, Historic England suggests it can be better to clean an entire surface rather than just trying to remove the graffiti.

Jamie says it is not always necessary. He spent some time researching fine art restoration some years ago because it occurred to him that if layers of dirt, varnish and paint could be removed one at a time on fragile works of art, it ought to be possible to do the same on the larger scale of buildings.

Removing graffiti using Restorative Techniques’ Thermatec superheated water system with a vacuum recovery unit to collect the material removed.

It turns out it can be possible, so paint (or other media) can be removed without disturbing lower levels of material it has been applied to. “You need the support of a good chemist who understands what you are trying to achieve,” says Jamie. He says he has even been on one course about cleaning paper, because, being absorbent, it has some lessons that are applicable to stone.

Another problem identified with graffiti is that it can still be visible as ‘ghosting’ after it has been removed. That can be tackled, and again Jamie says the chemists have helped.

By using a thickener, more active cleaning chemical can be kept in contact with the surface to be cleaned for longer to produce a deeper clean to remove graffiti. Without the thickener, a poultice might only remain active for 20 minutes. With it, it can continue working for perhaps two days.

The thickener also prevents the chemicals from being absorbed into the fabric of the building, which can itself be a cause of ghosting if it is not removed thoroughly.

Sometimes it can be important not to rub material into the fabric of a building. Just last month Jamie was dealing with cleaning the results of a fire lit against the tower of a church. Most of the mark was soot, but soot can be acidic or alkaline, depending on what has been burnt. If it gets wet the damage can be greater. It can’t be brushed off because it will be rubbed into the surface of the stone. So it was cleaned off using a dry but gentle microabrasive.

Although it is not graffiti, Jamie says the approach is the same: determine the substrate and what material has been applied, then find an appropriate way to remove it. An overriding principle of any cleaning is to try whatever you think might do the job on a small and unobtrusive area to test your hypothesis before going to work on the whole area.

Removing graffiti is one of the best ways of also removing the problem of it, because if it is left it will often be joined by more. The advice note says: “A responsive and consistent programme for graffiti removal tends to encourage graffitists to go elsewhere.”

The advice note does include a section on treating walls to make it easier to remove graffiti if it does occur, but warns that treatments, usually wax based, can change the look of the walls. It says: “Building local appreciation and understanding of the historic environment is probably the most effective way of preventing graffiti.”

This is the picture on the cover of the new Advice Note from Historic England concerning the issues of graffiti. It shows the Holy Rood Church in Old Town, Swindon, which dates from the 13th century.