St Lawrence Jewry Church: First major overhaul for Wren church since Blitz renovation

Julian Harrap Architects and Bakers of Danbury have started work on this important Grade 1 Listed church.

The first major programme of repair and conservation for more than 60 years has begun to the Grade I Listed St Lawrence Jewry Church next to the Guildhall, home to the City of London Corporation, the centre of government in the City of London.

Julian Harrap Architects LLP has been commissioned by the City of London Corporation to undertake a comprehensive programme of repair and conservation work to the church. The practice’s contribution includes detailed research and use of its highly regarded historic building knowledge to reinvigorate this architectural gem.

The work is being carried out by Bakers of Danbury Ltd with Imperial Stone sub-contracting. Both firms are respected for their expertise on historic and listed properties.

It is the first time since 1957 that any major works have been carried out to St Lawrence Jewry, although last time the even more substantial programme was to remediate the damage caused in World War II following a direct strike by an incendiary bomb during the Blitz.

St Lawrence Jewry after taking a direct hit by an incendiary during the Blitz in 1940.

The current project is a major and ambitious restoration of an important Wren church in its own right.

The exterior works include specialist masonry cleaning, starting with a Doff clean, nebulous spray and chemical poultices in areas of particularly difficult accumulations of dirt. Repairs to the Portland stone elevations and the restoration of 11 striking stained-glass windows originally made by the celebrated artist Christopher Rahere Webb (1886-1966) will also be carried out.

It is unusual to see a building of this stature in London in such a relatively neglected state these days. “It’s been unloved for so many decades,” says Andrew Coles, the Associate at Julian Harrap Architects in charge of the project.

One of the reasons it has been neglected is because of a long-standing dispute between the City of London Corporation and the Church of England over who should pay for it. With water starting to penetrate the fabric a resolution was starting to become urgent and in the end it is the Corporation that is paying for the external work of Phase One and the Church of England that will pay for the internal works of Phase Two.

The Church is remaining open during phase one of the project, which involves the cleaning and repair of the masonry and carved stonework, renewing, structurally reinforcing and thermally upgrading the lead-clad hipped roof over the Nave, re-roofing the Commonwealth Chapel, the Vicarage Apartment that was added in 1957 and the roof to the south-west of the tower.

The timber framed, lead-clad cupola and spire will be renovated and the lead gutters and downpipes replaced. Lightning protection will also be replaced and fibrous plaster ceilings will be repaired and structurally strengthened.

Phase Two is due to start next year. It will involve all internal works, including full electrical re-wiring, replacement of all water pipes and the heating system, and an upgrade of fire safety.

The layered history of St Lawrence Jewry Church, which is adjacent to London’s Roman Amphitheatre, a Scheduled Ancient Monument, makes it one of the City’s most valued heritage assets.

The site has been used as a place of worship since at least the 12th century, when a medieval church was founded there in 1136, although the discovery of burials dating from 1040 in Guildhall Yard suggest a church or chapel was already on the site by this date.

In 1666, when the Great Fire swept through London, the medieval church was largely destroyed and Sir Christopher Wren was tasked with designing a new church. The rebuilding was completed in 1677.

St Lawrence Jewry was the most expensive of the 51 churches rebuilt after the fire.

In 1940 the building took a direct hit from an incendiary bomb dropped during an air raid of the World War II Blitz. The interiors were incinerated but the Portland stone of Wren’s walls and tower, and one of the obelisks on a corner of the tower, survived.

A temporary chapel was created within the ruins, where services continued to be held. A bell was installed, which is today on the north-west roof and is still rung every Wednesday before services. It bears the inscription EECE POST IGNE, VOX (after the fire a voice) from Kings 19:12.

The bell rung for the services in a temporary chapel created after an incendiary direct hit in 1940 is still on the north-west roof and is rung every Wednesday.

Temporary stabilisation work was carried out immediately after the war, which included filling the crypt with concrete that now prevents access to the remnants of the 12th century church that was on the site.

The City architect of the time, Cecil Brown, oversaw the rebuilding of St Lawrence Jewry in 1954-57. Many of the finishes to the roofs, gutters, cupola and spire date from then and are, therefore, at the end of their service lives, as can be seen by the water ingress that Bakers of Danbury says has become an increasing problem in recent years.

The surviving Wren masonry suffers from heavy carbon staining and discolouration as well as ‘corrosion jacking’, a problem familiar enough in conservation caused by concealed iron cramps rusting due to water ingress, expanding and cracking the stonework. It has resulted in some quite sizable pieces of stone falling off the building.

For his reconstruction, Cecil Brown used quite shelly Portland limestone, so in order to match it a similar looking Whitbed is being used now.

Cecil Brown referred to detailed survey drawings of the church produced by John Clayton in 1848, which were instrumental in producing a faithful Wren reproduction.

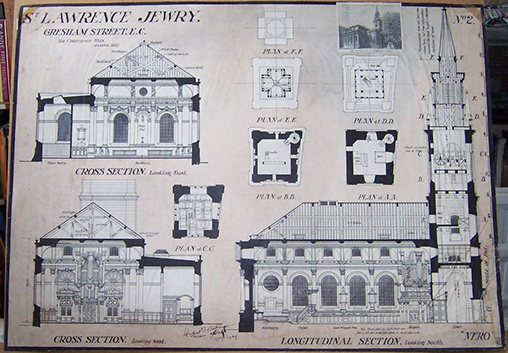

Julian Harrap Architects also referred to a measured survey drawing of the church by Hubert Bateman dated 1909 and photographs from the turn of the 19th/20th centuries, as well as a new measured survey using scanners and drones carried out by chartered surveyor James Brennan Associates.

The measured survey drawing of the church by Hubert Bateman dated 1909.

Andrew Coles says they did contemplate creating a digital twin but the nature of the work was expected to be small scale initially, even though it has since snowballed, and the digital twin idea was not pursued.

A revelation about the building following the cleaning has been that one of the Wren Portland stone ashlar walls was removed and replaced shortly after World War I.

It had been thought the wall was medieval, roughly built of a mix of materials because it was originally hidden in an alleyway. But Andrew Coles discovered it had in fact been Portland ashlar like the rest of the church.

The ashlar appears to have been stolen in the 1920s and replaced with whatever was to hand, which includes clunch, brick, ragstone, coursing tiles and ironstone. The insult was increased in the 1950s when the wall was repointed using hard cement.

Cleaning of the north elevation wall revealed a mix of masonry that was originally thought to be medieval but turned out to have been added in the 1920s when Wren’s Portland ashlar appears to have been stolen. The wall was repointed with cementitous mortar in the 1950s that is being removed and replaced with NHL3.5 lime.

The Diocesan Advisory Committee (DIA) did raise the question of replacing the wall with ashlar to match the rest of the building, but as the brief was to make essential repairs only it has been decided simply to remove the hard cement, gallet where necessary to fill large gaps and repoint using NHL3.5 lime mortar and coarse sharp sand.

Cecil Brown’s only major variation from the Wren original was the addition of a vicarage apartment in the north-west corner, where a highly ornate vestry was originally located.

Andrew Coles says: “St Lawrence Jewry Church, together with its historic setting, is a microcosm of London’s endlessly fascinating story, from Roman Gladiators to the Great Fire of London, Wren’s rebuilding and the destruction caused during the Blitz. It’s a privilege to undertake a project which will safeguard such an important building.

“Through meticulous archive research and inspection of the historic fabric we developed a deep understanding of the evolution, chronology and history of Wren’s St Lawrence Jewry. Repairs are considered on a stone-by-stone basis and intervention is justified with established conservation philosophy.”

Keith Bottomley, the Chairman of the City of London Corporation’s Projects Sub-Committee, says: “We take our role as the guardian of some of London’s most prestigious historic settings incredibly seriously. We look forward to seeing the St Lawrence Jewry Church fully repaired and conserved to ensure it continues to be appreciated by generations to come.”

This first phase of the project on the exterior of the church is due to finish at the end of next year. Budgeted at £4million, it is designed to return the Church to a sound state of repair and safeguard it for future generations.