In December, NSS reviewed the Kings & Scribes permanent exhibition at Winchester Cathedral (click here to see the review). Its opening marked the end of an eight-year building and conservation project that exposed usually hidden parts of the limestone walls and foundations and, with it, more of the history of the building. The exhibition is divided into three parts, one of which is called ‘Decoding the Stones’ (the others are ‘A Scribe’s Tale’ and ‘The Birth of a Nation’). Much of the work involved in Decoding the Stones fell to Archaeologist John Crook. This is his report.

The opening of the ‘Kings & Scribes: The Birth of a Nation’ exhibition at Winchester Cathedral marked the end of a building and conservation project worthy of comparison to the great preservation works of 1905-12, during which William Walker, a deep sea diver, spent nearly six years under as much as 6m of water replacing the cathedral foundations to stop subsidence of the structure built on the floodplain of the River Itchen.

As the current works evolved from construction to fitting out, the demands on me as the cathedral archaeologist moved from practical investigations and watching briefs to providing information about display objects, supplying measured drawings to model makers and, above all, undertaking the full ‘post-excavation’ analysis and report.

This was a time-consuming but essential task because there’s no point in spending several years recording a project if it is not written up for future researchers.

With that in mind, this is an appropriate time to consider what historical discoveries have been made since the idea of a new exhibition at the Cathedral was first mooted as long ago as 2011.

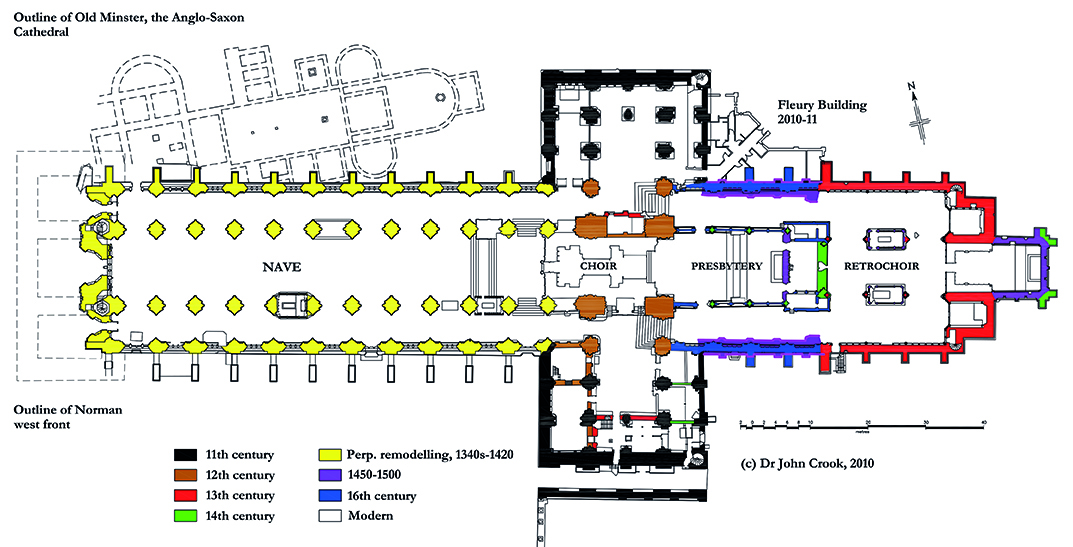

Above. John Crook's plan of the Cathedral.

Below-ground works

To make the exhibition in the Triforium Gallery accessible to everyone, a lift was installed. This required the excavation of a pit in the south transept to accommodate the direct acting hydraulic drive that elevates the lift. That pit was dug by hand (most of it single-handedly!). There were 9.5m3 of deposits removed, weighing an estimated 26 tonnes.

For an archaeologist, it was worth the effort just for the new insights it provided into the way the Norman cathedral was constructed.

At the bottom of the pit, about 2m below the tile pavement, a hard lime plaster surface was discovered. It was at exactly the same level as the crypt floor.

It became apparent that in preparation for building the cathedral, the Normans had excavated the entire site to a uniform level a little lower than the current level of the crypt floor and about two metres below the final floor level of the nave and transepts. They then laid a temporary plaster floor on which the plan of walls and piers could be marked out.

These areas were excavated to a slightly deeper level and oak piles were driven down through the subsoil to the gravel (as observed during the underpinning works during the 1905-12 programme).

On top of the trimmed piles tall foundation blocks were built, two metres or so high, so a visitor to the site would have walked among a labyrinth of walls that would soon be buried in backfill to bring the floor up to its final level.

The loam used for the build-up came from the monastic graveyard of Old Minster and contained a large amount of skeletal material, though not skulls or long-bones, which appear to have been buried separately in a great charnel pit, excavated by Martin and Birthe Biddle in the 1960s, just beyond the marked-out (though not yet built) west end of the Norman cathedral.

One of the 11th-century visitors to the site when the Norman cathedral was being built, perhaps a monk of the Old Minster that had stood on the site previously, was unlucky enough to drop his stylus.

A stylus is a writing implement used to make notes on a wax tablet. No doubt it rattled down a gap next to a foundation block and was lost. If the owner uttered any Anglo-Saxon expletives they went unrecorded.

The stylus, perhaps dropped by a monk.

The stylus, perhaps dropped by a monk.

Almost 1,000 years later the stylus gave us the best archaeological find of the whole operation. This fine late Saxon artefact is perhaps the earliest item to have been excavated from the cathedral as it currently exists and is now displayed in the new Kings & Scribes exhibition.

Before the discoveries made during the excavation of the lift pit, the tacit assumption had been that the Norman builders excavated a large pit for the crypt and deep strip foundations for the walls, arcade piers, and tower crossing piers.

The re-excavation of a service trench in the Chapel of St Alphege provided another discovery – the remains of the original south entrance to the crypt, answering to that on the north side which is concealed beneath a trapdoor next to the modern entrance. A capital was exposed, part of the arch at the bottom of a flight of steps leading down northwards into the crypt’s south aisle.

Over on the other side of the transept, the removal of the timber floor of the vergers’ vestry revealed the stone-lined pits that I have argued were an integral part of Henry of Blois’s treasury, intended for the safe storage of money (ingots and coin).

The decoration of the massively thick walls inserted into the transept’s west aisle links the structure with that supremely rich bishop – and he may have felt that his cathedral would offer more protection for his wealth than his palace at Wolvesey.

Priory plan evolves

Also briefly revealed was a wonderful group of re-used 13th-century decorated floor tiles, laid perhaps in the 17th century in the south-east corner of the room.

More obvious to those who walk through the Inner Close were the excavations for the foul water drain provided to serve WCs for choir members in their new vestries in the south transept.

This drain ran all the way from the angle of the transept and nave to the Judges’ Lodgings, and thus provided an amazing north-south section of the east side of the two cloisters, the main cloister and the smaller infirmary cloister to the south.

The excavation provided a glimpse of the inner wall of each cloister and of the north and south walls of the monastic refectory. This has allowed the plan of the priory precincts to evolve rapidly.

The stripping out of the late 19th-century WCs at the east end of the Calefactory (the south aisle of the transept) allowed the development of successive altar steps there to be traced, which provided a glimpse of what must have been a wonderful 13th-century decorative scheme.

Newly discovered wall painting

A wall-painting of St Benedict on the south side of the transept is well-known, but a new discovery on the east wall was the painted figure of what appears to be a saint being tempted by a small demon.

The newly discovered wall painting.

This appears to be part of a series of paintings featuring saints that once could be seen along the entire east wall of the transept. Tragically, in the calefactory the stripping of medieval wall plaster when the WCs were created has resulted in all except this one figure being destroyed. The one that does remain is now safely protected behind light excluding chains.

The piercing of the lift shaft up to the triforium level provided a unique view through a section of an 11th-century vault, albeit one that had been severely compromised by the subsidence that is so apparent in the south transept.

The vault had been formed of roughly tooled voussoirs made from Quarr stone, which comes from the Isle of Wight. Pockets at the corners had been backfilled with loose rubble to form a more or less level surface above the dome.

Vaulting exposed

The vaulting exposed by the hole cut for the lift shaft.

The vaulting exposed by the hole cut for the lift shaft.

The exposed section also allowed the history of construction at this level to be ‘read’. Above the levelling material was a thin layer of organic material, suggesting that construction had paused at this level for a year or more, allowing blown leaves and other debris to accumulate. The delay was probably the result of builders in the 1080s attempting to deal with the subsidence problem by vaulting over the Slype (a covered way between a cathedral transept and the chapter house or deanery).

Another main area of work involved the roof and vault of the presbytery where the main historical interest was working out the date of the various phases of works.

The main fabric of this part of the cathedral is 14th-century, but the project was evidently prolonged, perhaps delayed by the Black Death of 1348.

Thus, the clerestory window arches have details consistent with the period 1330-40, but their window tracery seems to have been designed in the early 1350s under Bishop Edington. It was probably not actually installed for a couple of decades after that as the glass in the window seems to be from the 1390s at the earliest.

Extraordinary as it may seem, the presbytery may have been a building site for about 80 years. Winchester folk must have been used to such delays, given the length of time it took for the nave to be completed.

This chronology is provisional and will, I hope, be refined by further analysis, which is still on-going.

Bishop Fox’s work

We can be surer of the date of Bishop Fox’s work. The reconstructing of the aisles came first and the insertion of his flying buttresses to support the clerestory elevations. At the same time he reconstructed the clerestory of the eastern bay of the presbytery, beyond the Great Screen that was by then already in place.

Then came the new roof, designed to accommodate the vault beneath. Wisely, Bishop Fox decided to build a wooden copy of Wykeham’s vault of a century earlier rather than risk using stone.

The roof has now been tree-ring dated to 1507-08. The presbytery vault is contemporary but cannot have been installed until the roof was built because during construction it was temporarily suspended from the roof timbers.

The carving of the vault’s decorative bosses must have proceeded apace in those years. It was certainly complete by early 1509, given that the future Henry VIII still features as Prince of Wales.

More recent interventions may be dated through more obvious means, in the form of ‘time capsules’ left behind and graffiti.

The roof and vault underwent a major refurbishment in the first decades of the 19th century, when one of the restorers, a certain D Bedford, left a heart-shaped design with the date 1838 on it showing that the easternmost bays of lead had survived for 180 years.

The roof and vault underwent a major refurbishment in the first decades of the 19th century, when one of the restorers, a certain D Bedford, left a heart-shaped design with the date 1838 on it showing that the easternmost bays of lead had survived for 180 years.

D Bedford's heart-shaped design dated 1838.

It featured an invented coat of arms and the initials VR for Queen Victoria, who had acceded to the throne the previous year.

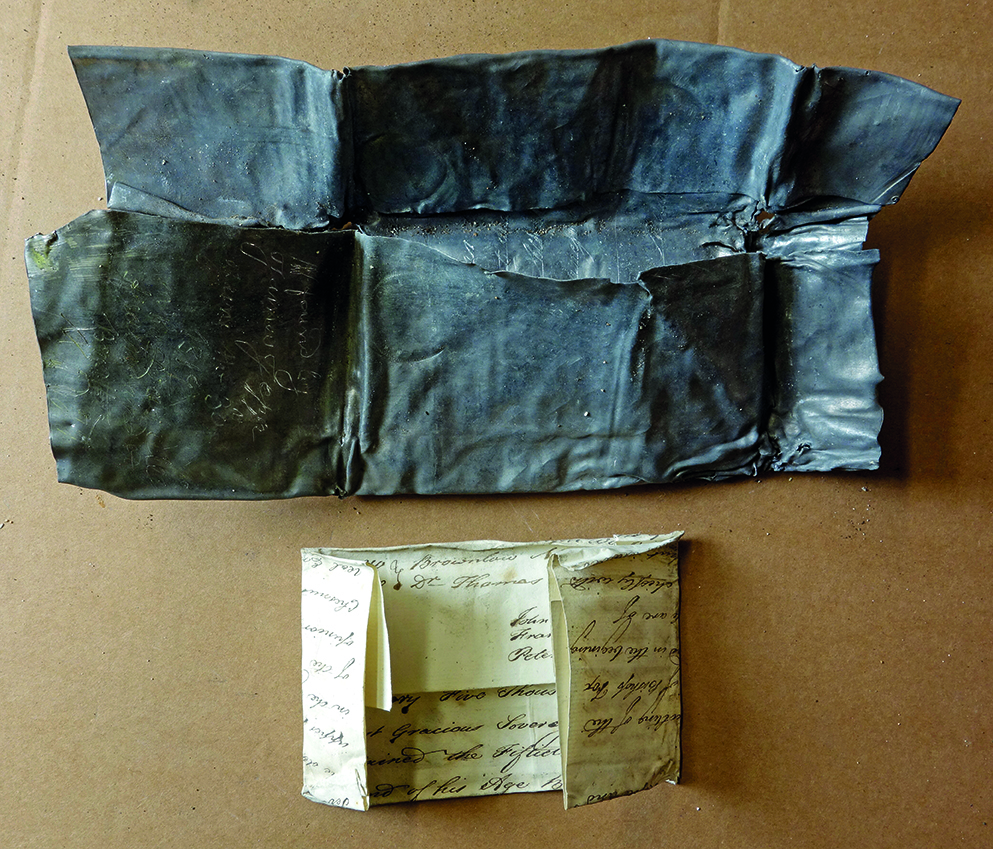

The vault had been conserved at a slightly earlier date. During our recent works the conservators discovered a folded sheet of lead, with various scratched inscriptions, enclosing a sheet of paper. The chronology proved to be complex.

The letter and inscribed lead that contained it left in 1808.

The letter and inscribed lead that contained it left in 1808.

The earliest inscription comprised the initials PTTS and the date 23 October 1808. Two years later (3 October 1810) Peter Thomas Twynham Stubington added a more lengthy inscription relating to how he and his brothers, who he describes as ‘Church Carpenters’, had repaired the south-east vaulting bay in English oak.

For good measure, Stubington wrote a similar account on a sheet of paper, which was enclosed within the folded lead together with a George III halfpenny of 1806. It seems likely that the account on the paper was a replacement for something similar deposited in 1808.

Stubington was a Freemason, and both the lead and paper inscriptions include an explanation of how two Lodges had merged in 1813 to form the United Grand Lodge of Ancient Free and Accepted Masons of England. On 30 June 1819, two other men working there, James Jepp and Alexander McKenzie, scratched another inscription explaining how they had found the capsule left by Stubington.

Time capsule

The next major intervention on the vault was in 1949. This time a more official time capsule was deposited in the hollowed upper surface of the boss of the Veronica near the east window.

It comprised two elements: photographs of the Cathedral and Winchester city taken by Dean Selwyn with annotations by him; and a tin formerly containing Zube throat pastilles into which had been placed a list of the carpenters and painters from the local building firm of Moreton & Sons who had decorated and repaired the vaulting.

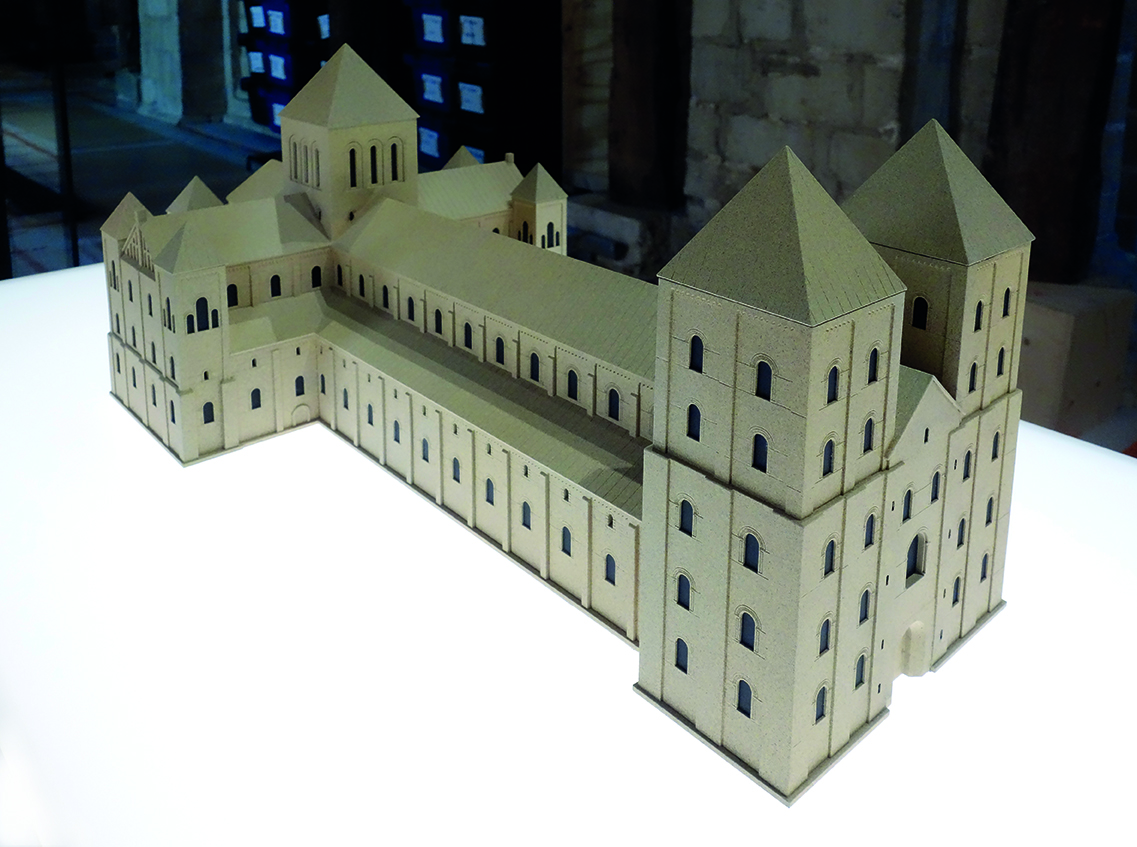

And what of the new exhibitions themselves? I am particularly pleased that the hypothetical drawing of the Norman cathedral I made years ago has been skilfully turned into a scale model. This work certainly focuses the mind.

A particular challenge was to work out the appearance of the Romanesque west front, for which we have little more evidence than the excavated ground plan. In my drawings it is broadly based on two churches in Normandy built in the same period with western structures that seem to match what little we know of Winchester’s.

This (above) is the scale model of the Norman Cathedral seen from the north-west to show the west front. The model was made using John Crook’s drawing.