Stone in housing : Demand for British stone picks up after Brexit vote

The housing market plays a significant role in the demand for stone products. The government would like more houses to be built but most in the stone industry are content with the current level of work, which for many has picked up following the Brexit vote.

Housebuilding picked up in 2016 although prices were still rising way ahead of general inflation, as they have been for years. Government official monthly figures published in November show the average price of a house in the UK rose a not exceptional 7.7% in the year to September to £217,888.

That disguises big regional differences. Prices fell in the North East and (unusually) in the South East, although from very different starting points. The average house price in the North East is £125,200, in the South East it is £312,600. Prices in London rose almost 11% to an average £487,600 (with a quarter now valued at more than £1million – many a lot more). In the East prices rose by more than 12% to £277,200.

That disguises big regional differences. Prices fell in the North East and (unusually) in the South East, although from very different starting points. The average house price in the North East is £125,200, in the South East it is £312,600. Prices in London rose almost 11% to an average £487,600 (with a quarter now valued at more than £1million – many a lot more). In the East prices rose by more than 12% to £277,200.

Prices rose most at the top end of the market, where stone is most likely to be used, with the average price of a detached house across the UK increasing 8.2% to £331,300.

The increases are in spite of a fall in the number of homes being bought, especially in London. The Bank of England Agents’ Summary says there was a slowdown in activity in London in particular, although sales in the UK as a whole show a seasonally adjusted fall of 4.3% between August and September (5.7% non-adjusted), with levels remaining lower than they were in 2014 and 2015. There were 11.3% fewer transactions in September than there had been in September 2015. The number of transactions matters because people are most likely to carry out home improvements, such as installing new kitchens and bathrooms, when they move home.

There might be good news on the horizon, though, as the latest market survey from the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) reported a modest increase in new buyer enquiries in September – the first since February. The volume of lending approvals for house purchases also rose in September (by 3.2% compared with August), although this follows three months of consecutive falls. The volume of lending approvals remains around the same level as it was early in 2015.

On the supply side, RICS reported that the number of homes being put up for sale fell again in September compared with August, continuing the trend of the past seven months.

The latest Office for National Statistics (ONS) figures for output in the construction industry show a 1.3% month-on-month fall in new-build housing in August, although it remained 8% higher than in August last year.

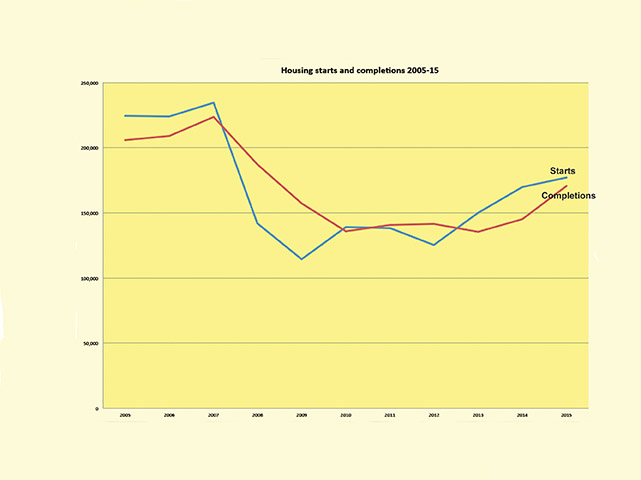

The government has set its sights on getting 200,000 houses a year built up to 2020. It is difficult to see how the target will be met, although proposals for a £3billion Home Building Fund announced at the Conservative Party conference in September by Communities Secretary Sajid Javid and a £2.3billion Housing Infrastructure Fund announced by Chancellor Philip Hammond in the Autumn Statement on 23 November should help.

“We’ll use all the tools at our disposal to accelerate housebuilding and ensure that, over time, housing becomes more affordable,” said the Chancellor.

The Home Building Fund is intended to release £1bn of short-term loans for small builders, custom builders and ‘innovative’ developers, by which it has become clear it means off-site manufacturing.

The government complains that planning laws are holding back development, but research published in January, carried out by Glenigan on behalf of the Local Government Association, showed there were a record 475,647 outstanding housing consents waiting to be built.

The study showed a rapid increase in the number of planning consents not being actioned over the past few years with a record 212,468 planning applications for housing approved in 2014/15. This was more than the previous high point of 187,605 in 2007/08.

The Local Government Association (LGA), which represents local authorities, wants its members to be able to build more council houses as well as being given powers to charge developers full council tax on every unbuilt development.

One of the reasons the building industry gives for the lacklustre level of activity is a shortage of skilled labour, a problem which only seems likely to get worse with the construction industry’s forecasted annual recruitment need up 54% from where it was in 2013, yet 10,000 fewer construction qualifications being awarded by colleges and universities and to apprentices last year. There were 58% fewer completed construction apprenticeships than in 2009, a situation the government hopes its new Trailblazer apprenticeships will help to rectify.

The repair & maintenance side of housebuilding has also had fluctuating fortunes. It decreased quarter-on-quarter by 3.2% in the three months to September and 3.4% compared with the third quarter of 2015.

This is the background against which stone companies supplying housebuilders are working. Yet plenty of stone companies are working flat out to keep up with demand from the domestic sector.

Many of the British dimensional stone extractors supplying stone for housing survived the economic downturn after the 2008 credit crunch thanks to continuing demand for higher value stonework from the top end of the market. With confidence in stock markets shaken worldwide some looked for the security of investing in land in a politically stable part of the world. And they wanted to build on that land, especially as the downturn gave them the opportunity to negotiate some bargain prices with product suppliers and builders.

The UK fitted the bill in terms of stability and, with a bit of prompting from planners, perhaps, the grand new houses being built on the acquired land often used appropriate local stones as walling, ashlar and architectural masonry.

Stone processors working in interiors did not do so well. The collapse of the housebuilding market in general, including repair & maintenance as households reduced their borrowing, led to the closure of a lot of kitchen showrooms and the stone companies supplying them with worktops. This was exacerbated at the start of 2009 when banks withdrew their financial support, including overdrafts, to many of the stone processors. There had been about 1,200 companies, some very small, working in the worktop sector and about a quarter of them were forced out of business.

There was some downsizing by the companies that survived as the low level of activity stretched on. As it has picked up again many companies have found it difficult to recruit the skills they need. In any case, technology has moved on and so has the general acceptance of it, which has led to a lot of investment in new machinery by stone companies in the past two or three years.

The new, large format engineered stones and ceramics that have entered the repertoire of stone processors have also prompted some of that investment, as well as giving the stone companies a greater range of products that helps them grow their share of the worktop market in the domestic sector – a market valued by a report endorsed by the KBSA, the specialist retailers association, at just over £571million in 2015.

And, of course, it is still a competitive market. Although profits have improved and the pricepoint has moved higher in the past four years, customers are still sensitive to prices and will look around. That is another reason why there has been so much investment in machinery by the manufacturers.

As for the impact of the Brexit vote, it is still early days but so far most companies have only seen business pick up since the votes were counted.

Last year, the autumn rush seemed less of a rush than usual for many companies and 2016 got off to a relatively subdued start for many. But after the referendum, stone companies have reported a significant increase in enquiries and sales.

Certainly most people did not anticipate the vote would be in favour of leaving the EU, but the crash predicted by those opposed to leaving has not materialised. In fact, the result seems to have injected confidence into the UK in general.

The only real downside seems to be the fall in the value of sterling, which has already been reflected in the increase in prices of imported natural and engineered stones and stone processing machinery.

As the weakness of Sterling starts manifesting itself as higher energy bills, food prices, the cost of clothes and most other day-to-day expenses for consumers and businesses there will be less disposable income, which would be expected to subdue demand. If wages increase to compensate, companies’ costs will increase further and prices will rise further, which would be expected to trigger a rise in interest rates by the Bank of England, increasing the cost of borrowing. If wages do not increase, demand will fall and economic growth will be reduced. Many stone companies Natural Stone Specialist has spoken to believe that somewhere down the line the level of work will ease off. How much might depend on the details of the Brexit negotiations.

Speaking as the Chairman of Stone Federation Great Britain’s Quarry Forum and a member of the Mineral Products Association Dimension Stone Group, Marcus Paine of Hutton Stone in Berwick-upon-Tweed, on the Scottish borders, thinks the rise in price of imports, both from the fall of the pound and the increasing costs of shipping, presents an opportunity for stone producers in the British Isles if they can take it.

“You never think world affairs affect you much but they always somehow do. With the fall in the pound we gain almost by default as people compare prices. The important thing for us is to build on that and really develop it.

“We need to do better in the British stone industry at promoting our own products. We shouldn’t complain about imports, we should be shouting about why our products are great.”

He mentioned Burlington, the company with eight slate and limestone quarries in Cumbria that exports half of its stone, much of it to America. “I feel the rest of us should follow that lead. If Burlington can sell abroad at higher value, surely we should at least be able to sell our stone into our own market.”

In Scotland, Hutton has formed a co-operative called the Scottish Stone Group with Denfind and Tradstocks specifically to promote indigenous stones to local authorities, developers and main contractors. Marcus says the Group has been well received because of its wider aims of reducing the carbon footprint of building and keeping jobs in the area.

“The arguments are easy to make but as an industry we need to be not so lazy and start to make them,” says Marcus.

The housing market has grown for Hutton Stone in the past 18 months – “I mean, significantly,” says Marcus.

Graeme Haddon was President of Stone Federation Great Britain until he handed the chain of office on to Tim Yates at the Federation’s AGM in November (see page 39). He has just left Land Engineering, based in Glasgow, to join construction company and developer Ashwood Scotland in Bathgate, West Lothian. He says there was no fall in workload after the referendum.

He feels there is uncertainty about what Brexit will mean, especially in Scotland where most people voted to remain in Europe. There is an element of ‘wait-and-see’, which is subduing demand and making it difficult to predict what will happen next.

“The biggest challenge we face is the skills shortage. There’s not enough skilled people – but that was true before Brexit. We need certainty. That will drive investment and training. Nobody wants to commit to long-term funding without certainty. I’m in favour of training more people here in the UK and getting a strong indigenous workforce. We haven’t got that because we have concentrated far too much on degrees rather than hand skills. People don’t feel they have a choice.”

At the other end of the country, at Gallagher’s in Kent, where Kentish Ragstone is quarried and processed, Vince Tourle, who heads the dimensional stone side of the business, says the referendum does not seem to have made any difference. He says there is still plenty of walling stone being sold and a big increase in the number of houses being built compared with recent years. He says there is also a steady flow of sales of stone for restoration and conservation, although not as much into London as he would have expected. The harsh days of the economic downturn after 2008 are receding and year-on-year sales improving. “We have our heads above water,” says Vince.

Further west, on Purbeck in Dorset, Lovell Stone Group, which added Hartham Park Bath stone underground quarry to the four other quarries it operates this year, says business was fairly quiet earlier in the year. But, says James Hart, one of the brothers who run the company: “On the day we found out about Brexit it suddenly got very busy. We’re now gearing up for one of our best ever halfs and there are lots of quotes going out, which looks good for next year. Whether it’s as a result of Brexit or just coincidence I don’t know”.

He says he has never known such a demand for building stone at this time of year. It would normally be a time when Lovell would be putting stone into stock ready for the year ahead, but walling is going out as fast as it can be cropped.

James and his brother Simon moved into dimensional stone production when they took over the Lovell Purbeck quarry in 2009. As they have added four more quarries and expanded their factory appreciably since then they would have expected growth. They also get a lot of repeat business as their reputation becomes established. “Sales this year will be better than last year across the board and last year was our best year ever,” says James. But he adds: “I reckon we’re not going to know whether Brexit was the right or wrong decision until the medium term – five or six years down the line.”

Darren Roberts, the newly appointed Commercial Director at Johnsons Wellfield Quarries (JWQ) in Yorkshire, agrees. “It feels like it’s too early to say,” he says. But adds that Johnsons has certainly become busier since the referendum result was announced and it will be working at full capacity for the next three months to get out the orders it has already taken. “It has a promising feel to it.”

Darren describes the JWQ natural stone business as the jewel in the crown of the Myers group of which it is part. It employs 80 of the 360 people in the group and supplies the group’s own builders merchants with natural stone products such as heads and cills. And whatever Brexit might eventually mean, Darren says: “We’ve just got to get on with it. It’s all we can do.”

In the East Midlands, Daniel Wilson at Stamford Stone, which is a major supplier to housebuilders around Northampton, into the Cotswolds and even further afield, is just as philosophical. He was surprised to see sales pick up after the Brexit vote and says: “I think the world has gone a bit berserk but it’s all right for now. In two or three years’ time it might be a different matter.”

These days, Stamford Stone imports stone for paving and flooring as well as quarrying its own stones from Medwells and Greetham quarries. There has been an inevitable price increase of the imports as a result of the fall in Sterling post-Brexit but Daniel says everyone else is in the same position, so he does not feel it will disadvantage him particularly. And if customers decide to buy the stone he quarries instead, he’s not complaining.

Adrian Phillips, who owns Black Mountain Quarries on the Welsh borders and DeLank granite quarry in Cornwall, has a similar story. “Sales are holding up very well at the moment, I have to say,” he told NSS. “The sky hasn’t fallen down. There will be a few rocks in the road ahead, but it’s how we react when that happens. I think the biggest threat is lack of confidence. If we have confidence we will be fine.”

Black Mountain Quarries also imports stone as well as operating its own quarries, although sales of the imports fell after the crash of 2008 and took a long time to start recovering. Adrian does not believe the fall in Sterling will impact on that recovery because everyone else will face the same level of price increase.

On the other hand, Black Mountain is also exporting its Callow stone to Canada on another phase of a project for which the stone has been used previously. The fall in the pound means the Canadians are paying less for the stone even though Adrian is getting a 10% higher Sterling price for it.

There are some particular concerns about what Brexit might mean in Ireland. Niall Kavanagh, the Managing Director of Irish Blue limestone producer McKeon Stone in Co Laois says on the positive side it has already meant the cost of machinery and material bought from the UK has significantly decreased.

On the negative side, for McKeon Stone as an exporter of Irish stone to the UK, the currency volatility is less attractive, reducing demand and / or margins for the stone.

Niall says: “A big concern in Ireland would be the reinstatement of a ‘hard border’ between the North and South. That would make life very difficult for the free flow of goods and services between the two.”

Clearly there are some concerns among stone companies going forward, but for now many are enjoying better times than they have known since the heady days of 2007.