STONE PROCESSING TECHNOLOGY

One of the benefits of a 3D representation of what you are about to produce is that if anything is wrong with the design it is obvious in the virtual world, rather than having to wait until it becomes apparent in the finished masonry of the real world.

At some point in the not very distant future someone will pick up this copy of NSS and be bemused to discover that in 2016 most stonework was still designed in two dimensions.

The design part of the construction industry is in transition, moving from traditional 2D to a more virtual 3D world, especially with what most in the architectural masonry sphere will recognise by now as BIM (building information modelling).

There are already some stone processors giving customers 3D impressions of what the finished stonework will look like, whether they produce the pictures themselves or they are produced by specialist designers who have detailed the stonework and its production schedule. Some of the illustrations are almost photographic quality – and, indeed, some are produced using photographs of the stone that will be used for the project.

One or two stone suppliers have even gone a step further and are using 3D printers to give customers physical models of what they will be producing in stone. This is currently fairly expensive, so it depends on the customer and what is to be produced.

The rapid expansion of processing power (most of you will be familiar with Moore’s Law) is speeding up and reducing the cost of using computers to do jobs that it would, just a few years ago, have been unthinkable for them to do.

The fear of being left behind has been apparent in the level of investment in CNC stone processing machinery of the past three or four years. Certainly there was some catching up to do after the cautious approach taken by most companies in the aftermath of the banking crisis, but now some companies are racing ahead.

The fact that Roccia Machinery has agreed to take on the distribution in the UK and Ireland of the robots from Italians T&D Robotics speaks volumes. As Roccia Director Darren Bill said: “Their time has come.”

It is true that computerisation does still divide the stone industry and there will, no doubt, always be a demand for hand skills. But… There are fewer companies all the time that can, or even want to resist the inexorable march of computers into the workspace.

Because, whether you are aware of it or not, if you produce masonry of any kind, including interiors, for the architectural side of the industry you are no longer just in construction but have become part of what is now known as the AEC industry (architecture, engineering and construction) that consists of the separate players who work together to bring a project to fruition.

While many firms have already started the transition to an ‘intelligent’ model-based process, the full potential of BIM can only be achieved by the open exchange of design and non-design project information among the key project stakeholders, including all the trade subcontractors, says Stefan Larsson, CEO of BIMobject, which is a cloud-based portal of manufactured building and interiors products. BIMobject claims to have more than 150,000 active BIM users that together have downloaded more than 4million digital products as BIM objects from bimobject.com. The site has been visited by more than 1.5million unique visitors and the products on it have been viewed more than 15million times. This is the marketplace the architectural side of the stone industry is working in today.

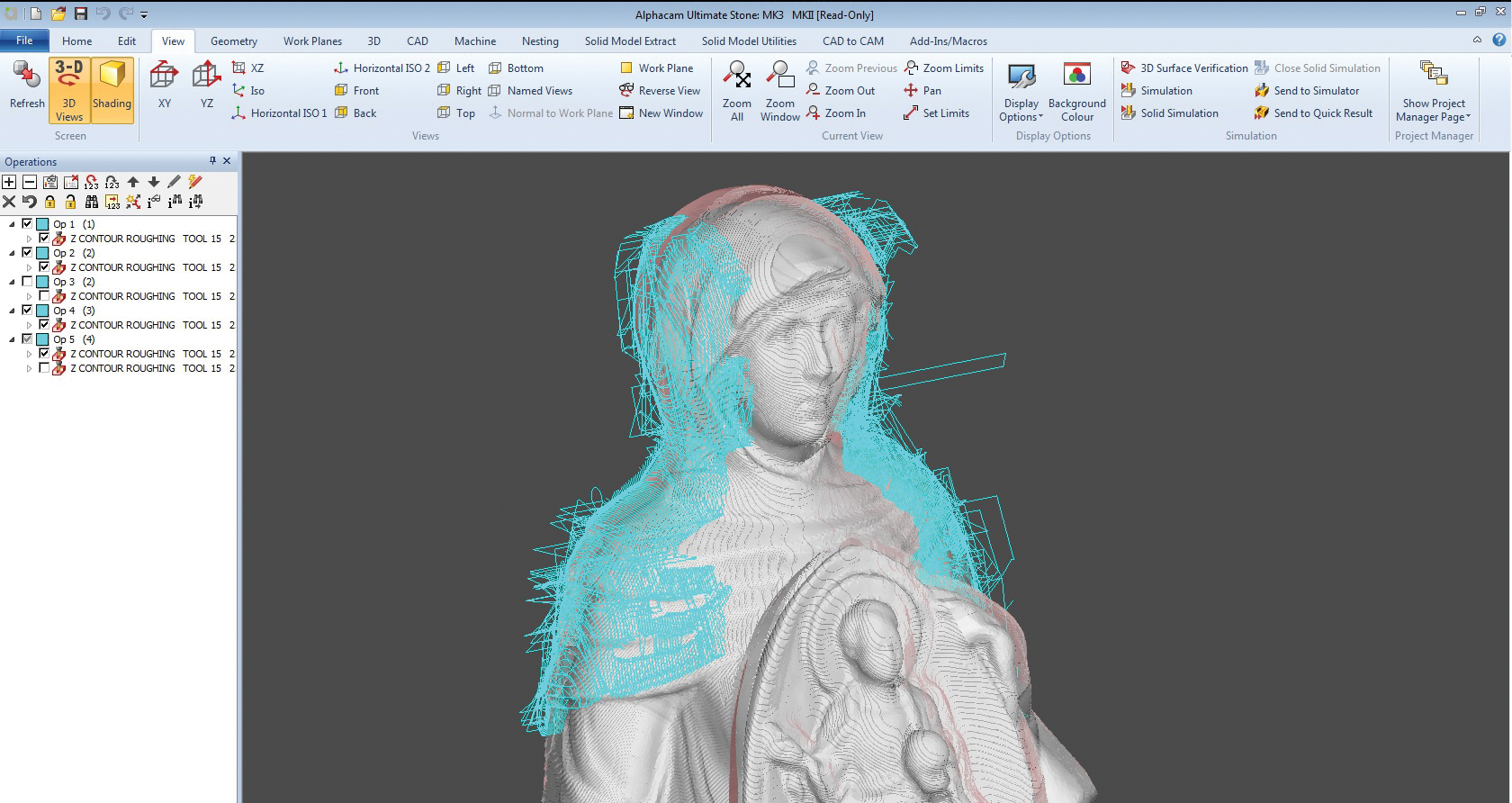

And if the design is already in 3D it makes sense to transfer it straight to 3D in manufacturing. There are various companies bridging the gap between computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing. One that has made a special bid for the stone processing sector is Alphacam. It started at the top end with robots but is gradually spreading throughout the whole sphere of CNC stone processing.

It was because Roccia was already familiar with Alphacam (because it is used on the GMM saws that Roccia sells) that it felt comfortable taking on the sales of T&D robots, which also use the software.

Just lately Alphacam has also started working with Sasso, another Italian manufacturer whose saws and edge polishers are being sold in the UK now by Pat Sharkey Engineering. The first K900 five axes Sasso saw was being installed at Ian Lowes’ Old Carlisle Stone Company as NSS went to press in February.

As Michael Pettit, the Alphacam sales manager for Europe, the Middle East and Africa, says: “One of our strengths is having a subsidiary in Italy. Our product is developed with the help of the OEMs [equipment manufacturers]. We’re working closely with them and that controls how we develop the software.” He points out, though, that the software is written in the UK and Ireland.

And it is written specifically for stone processing, which Michael Pettit says is different and in many ways more demanding than most of the CNC programs from Alphacam because of the variety of operations involved, the tool changes required and the change from sawing to milling. “It’s a unique process,” he says.

As the pictures on the previous page show, the T&D robots now have the capability of holding not just a milling head, but also a wire saw and a waterjet cutter.

And however precise the software, the machinery and the tools it is driving also dictate the quality of the finished work. Some stone processing has become precision engineering, with accepted tolerances below ±1mm. To achieve that, machines have to work accurately and smoothly, without lurches or jerks, while operators still expect them to work quickly.

The combination of powerful software and exquisitely engineered machines has expanded the potential of what it is possible to achieve in stone to previously unimagined levels.

It is not just the robot arm that is opening up new possibilities, either. At the Marmomacc exhibition in Verona last year one of the most impressive exhibits was the Fuego wire saw being launched on the Breton stand. A mighty machine with up to 10 axes (including two from the block-holding cart), it was being demonstrated as having sawn out a nautilus shell pattern in a great block of rock.

Breton, whose machinery is used on some of the most sophisticated stone processing lines in the UK, took over wire saw manufacturer Bidese Impianti in 2011. Now the first of the new Fuegos to come to the UK, albeit a more modest four axes version, is on its way to Portland in Dorset and the factory of Albion Stone.

The picture on the right gives an indication of the complexity of value-added work that can be achieved by the 10-axes Fuego. That would not be possible without sophisticated software, considerable processing power, high specification diamond wire and a machine manufactured to the highest standards.

Admittedly the number of customers who want stonework as complex as that pictured on the right will be limited, but the Fuego is ideal for producing cylindrical / tapered columns, stone casings for columns and worked stone for interiors.

The hi-tech Fuego comes in at the top of the Breton range of wire saws, but there are plenty of simpler Bidese and Breton Easywire block squaring wire saws working in the UK.

Another sophisticated technology starting to make an impression in stone processing is waterjet cutting. It has been around a long time – the first, relatively low-powered systems appeared as long ago as the 1930s. But, like everything else, waterjet cutting is becoming faster and more versatile with ever greater capabilities.

The cuts are more precise these days because of the automatic compensation for the splaying out of the jet of water and normally there is the option of having a tilting head to cut at angles.

There are still not many stone processing workshops in the UK that have a waterjet cutter, not least because for most jobs a disc is quicker and cheaper. But it is something more companies are looking at because water has the advantage of being able to cut through just about anything without a tool change, which starts to look inviting if you are working a variety of natural stones, engineered quartz and the latest generations of sintered stones and ceramic products, where having to change the discs frequently can lead to a lot of down time.

Intermac, the company that really opened up CNC processing in the stone industry in the UK and Ireland during the 1990s with its ‘Master’ workcentres, is now selling a lot of waterjet cutters worldwide, plenty to the stone industry internationally but also to many other industries for cutting wood-based products, metals, ceramics or any other sheet material from which precision parts can be cut. And it is from sheet material because although the T&G robot can carry a waterjet head, it is not a good idea to be shooting it off at random angles.

Even without the garnet abrasive used for cutting stone, the water pressure is at least 3,800 Bar (380MPa) and can be as much as 6,000 Bar. If the waterjet penetrated your arm (or anywhere else) even at the lower pressure it would almost certainly kill you because it would shoot up your veins and stop your heart.

There are hybrid versions of waterjet / disc cutter bridge saws available. There is one company that says it intends to buy the UK’s first Breton CombiCut, which has been on the market for a few years, but the machine is not here yet.

Another disc-cum-waterjet was launched by Prussiani Engineering at Marmomacc last year. It is the five axes Cut&Jet, characterized by the combination of the blade’s speed, the versatility of the waterjet and the efficiency of Prussiani’s patented Cut&Move manipulator.

The electro-spindle of the Cut&Jet disc-holder has automatic variable speed through an inverter. The blade can tilt automatically through 0º to 60º (or be at 90º). The waterjet and its abrasive forms an independent second head with automatic tilting from -5º to 60º.

The machine is rigid for good cut quality while an electronic feeler automatically measures the thickness of slabs for perfect 45º mitres.

This combination minimises waste of materials and, especially, the time associated with moving slabs from one machine to another. And the reduction of down time is a major plus of the Cut&Jet. It can perform the full cutting cycle of an

L-shaped kitchen countertop with rectangular internal holes and either (or both) straight and 45º edges without any intervention from the operator.

The diamond blade partially makes the internal and external cuts and the waterjet finishes them off at the corners.

Coming next, promises Prussiani, are versions with automatic slab loading and unloading, with rotating tables to reduce downtime even more, especially that dead time of unloading finished parts.

One of the best known names in waterjet cutting is that of Americans Flow, whose products are sold to the UK stone industry by The Waters Group.

Flow’s new software suite, FlowXpert 2015, allows you to work more effectively in 3D more easily. Engineered by SpaceClaim, Flow believes FlowXpert 2015 is the world’s first fully integrated 3D modelling and waterjet pathing software package. With it, you can import, create, modify and path 3D geometry in a single program.

SpaceClaim has taken full advantage of Flow’s 40 years of waterjet expertise to produce faster, smarter, interactive modelling in a familiar interface. FlowXpert incorporates waterjet application tips, material cut speed knowledge, improved pathing algorithms and expanded lead in/out customisation. The program estimates what steps are needed to create and make the cut, automatically detecting and fixing any path errors.

Another innovation is Flow’s DynaBeam non-contact laser device used to determine the precise distance from the Dynamic XD cutting head to the material being cut, so the head does not touch the material and risk marking it.

This precision measurement device ensures that standoff height and cut quality are maintained throughout, so the material being cut does not have to be flat and smooth. The DynaBeam can also be used to map the topography of the surface in advance of running the cutting program.

Two UK companies that have invested in Flow technology are Midland Stone Centre in Northamptonshire and Precious Marble of Bedfordshire. Their drive to incorporate Dynamic Waterjet XD stemmed from their desire to process difficult materials more easily.

By working in close partnership with the Waters Group, Flow are providing waterjet systems and support throughout the UK & Ireland.

But back to robot arms. Because although the robots of T&G mentioned earlier have been designed specifically for the stone industry, they are not alone in that. Another robot arm system designed with the stone sector in mind is the Transformer from French stone machinery company Thibaut.

For more than 50 years Thibaut has been making stone processing machinery. It has developed more than 80 machines for processing granite, marble and engineered stone of various kinds, patented

50-or-so innovations and sold 5,000+ units to 70 countries.

The Transformer can be a six, seven or eight axes machine. The high performance software has been specially developed for stone processing to perform complex milling and shaping operations.

The compact spindle rotates at up to 10,000rpm, carrying the expected variety of tools down to the finest for engraving. It has a reach radius of 2.5m and a 21-space tool magazine plus one specific space for a saw blade, so it can work with little or no human intervention once it has been set up.

The sixth axis allows you to work five faces (edges and top) of a block without having to move the workpiece. Inclined chamfers, concave and convex elements through to complete masonry such as classical order capitals and 3D sculptures can be achieved.

Most robot systems combine different software packages for design and manufacture, which is not easy. But driving Thibaut’s Transformer is the company’s

in-house software that combines computer-aided design and manufacture, because the robot uses a version of the same T’CAD T’CAM software that users of Thibaut three, four and five axes CNC saws and workcentres will already be familiar with.