Clare Howcutt-Kelly meets Ryan James

A blue Transit pulls up outside my house at about 5am one morning in May. It’s riding suspiciously low as if laden with a load of gold bullion. The driver – tall with a no-nonsense Yorkshire accent – invites me to look in the back. I slide open the door and on the floor is something bulky. It is not gold but it is precious, and I’m shocked it’s not protected with bubble wrap at the very least.

“It weighs a tonne. Literally”, he explains with a tone that suggests I worry too much, “Well, it won’t go anywhere will it?”

It is going somewhere. It’s going to RHS Chelsea Flower Show and we’re going, too. But ahead of us is a three-hour drive into central London in a questionable motor.

Ryan James is a sculptor and carver and the work in the back of the van is a wall fountain for designer Holly Johnston’s Bridgerton-inspired garden sponsored by Netflix at the Show. Carved from a single block of sandstone, it features a cameo portrait of Penelope Featherington accompanied by the words ‘even a wallflower can bloom’ which are, Ryan says, carved to resemble the Netflix font.

I have packed a Thermos of tea and Ryan rummages around before offering a stained old mug to have a quick brew before we set off. There is an ease about Ryan – he lives in the moment, talks freely and is solutions-orientated. Conversation is easy, the opposite of trying to get blood out of a stone.

Ryan has a degree in fine art from Plymouth University but when it comes to sculpture and carving, he is self-taught. When I first visited his workshop at Traditional Stone in Horbury he admitted he didn’t know the names of all the tools, but who cares? He most definitely has command of them.

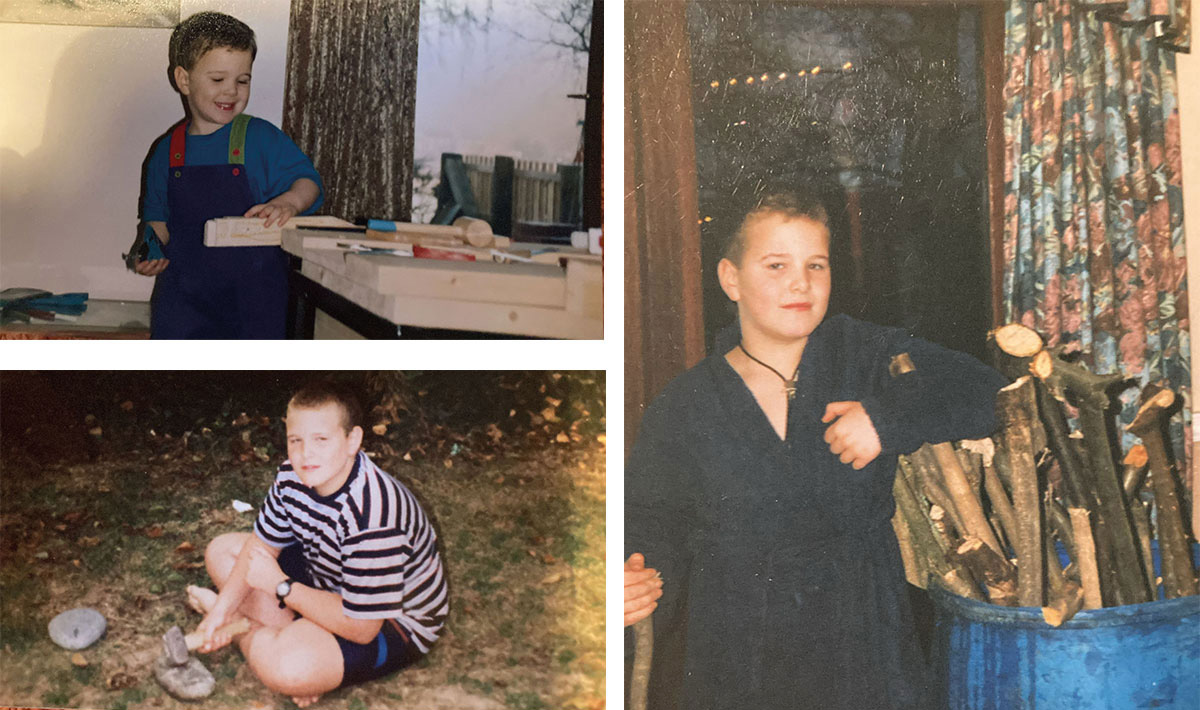

He’s been figuring out his own way most of his life and, as we talk – I can hear the voice of his inner child; his wonder and curiosity has never been snared by the trap that can, at times, be adult life with its routines and responsibilities.

His parents Dean and Susan, brother, Sean and wife Jade are, he reveals, his biggest influences.

“Mum’s really artistic and my dad’s a builder, but he’s always had an artistic side. Whenever we’d go on holiday, he’d always be pointing out the architectural carvings and features. I’ve always loved da Vinci and the way he figured stuff out and that type of that drawing – a fusion of engineering and art.”

Ryan was often found in the garden and was taught to carve stone by his dad; woodworking was another hobby he enjoyed. Ryan was also a proud member of a walking stick club

Surprisingly – and I must suppress a smile when he says this – at 14, he was a member of the local walking stick making club. Every Thursday night, he would “go to this working men’s club, have a pint of John Smith’s and talk about walking sticks.” An interesting hobby for a teenager in the 90s perhaps, but he won first prize at the Penistone Show for the first stick he ever made – so who’s laughing now?

“I loved making walking sticks, loved whittling with my penknife. Me and my brother used to carve out initials into a potato and melt lead on a fire in the garden and pour it in. I loved anything to do with carving and I remember Sean and me always up to something. He's always been really creative and is fantastic at drawing. He produces really quirky stuff and has helped me come up with some great ideas."

By eight, he was carving stone – an ammonite first (which is on display in his workshop) and then his dad taught him the basics of carving and lettering: “I carved an Elvis sign for my nan because we’re all huge Elvis fans.” Later, his GCSE coursework carvings included a mouse and a snake.

The Spanish alabaster portrait of Ryan's grandad was carved during lockdown

Of all the work he keeps in his studio, a portrait of his granddad, Leonard, is perhaps the most poignant. Carved in Spanish alabaster, he completed it during lockdown as a tribute to his granddad and the older generations who struggled with isolation when restrictions were imposed.

When he talks about what and who inspires him, there is more than a doff of the cap to the North’s industrial heritage. “There’s sculpture in what they did –old bridges and things that they made.”

Yorkshire’s rival county, Lancashire also produced one of his heroes, Fred Dibnah.

“Skint Northerners worked hard but didn’t really reap the financial rewards. My granddad used to work in the pit as an engineer so doing a portrait of my him came from all that, I wanted to celebrate a normal working man rather than being a portrait of a royal or a famous person. Art shouldn’t just be a luxury for the rich.”

For immortalising his granddad, he won the Tony Stones Award at the Society of Portrait Sculptors FACE2021 exhibition. It was this piece that gave Ryan the push to become a full-time sculptor. But it wouldn't have been possible without the support of Jade who continued to work full time.

“Jade is mega. I run all my ideas by her first. I tend to go for a more monochrome colour palette but Jade brings colour into every aspect of our life together.”

At primary school, Simon Todd, a Yorkshire artist and creator of wood and stone site-specific sculpture gave a talk at his school which also sparked something in the boy who loved his pencils.

And his pencils are still one of his favourite tools today, you’ll find them all over his workshop and tucked behind his right ear. He begins each project with a highly-detailed sketch before working out the scale. I’ve never seen him use a computer and there’s no mention of CAD software here. Instead, he keeps A4 hardbound sketchbooks close by and fills them with intricate drawings of projects in various stages – some just seeds of ideas that might one day bloom.

As coincidence would have it, one of his first sculptures was carved on site where Simon Todd’s wooden statue had once stood in the village of Clayton West where Ryan spent his childhood. Called the Spirit of Clayton West Sculpture, it celebrates the local heritage and those who contribute to the community; there are nods to his own family – his grandfather worked at a local mine while his grandmothers both worked in the mills. There are local landmarks carved into the stone including the church where his parents were married and plenty of animals including his dog Eiger, (who died before it was completed) are also carved there.

Ryan working on the griffins

One of his most notable projects was the creation of two four-tonne griffins for a private client. You’ll struggle to spot the differences between the pair of them although he can. This process for him was I think, a defining moment in his career and he developed his own working methods – a numbered grid system hand drawn onto each griffin, the use of a mirror and trial and error. Thankfully, not too much of the latter. He shared much of his progress on his Instagram account, and this was how most people came to know his name.

For the griffins, he used Howley Park sandstone quarried in North Yorkshire. Clare Dunn who worked for Marshalls at the time made the introduction and arranged for Ryan to visit the quarry and select the blocks. The team at Traditional Stone transported them back and prepared them by cutting a flat base. When the griffins left the workshop months later, you could sense these beasts had clawed their way into his heart and made an impression that would remain with him for a lifetime.

The workshop became the backdrop for many of his Instagram videos

By Ryan’s own admission, 2024 was an epic one, completing the griffins, creating the Bridgerton bespoke fountain and he also travelled to New South Wales to work with fellow Yorkshire native, Emma Knowles, founder of Stone of Arc and The Great Australian Stone Festival.

In 2024, Ryan also expanded his team with the addition of Endrit Rama who had worked for a larger company back home in Albania. With a degree in Classical Sculpture his drawings, like Ryan’s are intricate. Of Endrit, Ryan says: “He’s brilliant, very learned with clear methods and knows how to do mega architectural carvings. He knows all sorts of techniques and I’ve already learned a lot from him.”

Endrit’s first large-scale project with Ryan was the bust of a Highland cow and animals – real or mythical – are often being shaped into life in the workshop. He spends a lot of time studying anatomy with a focus of muscle definition and his pursuit of translating fluid forms into stone can verge on obsession: “I can’t let things go if they aren’t right. That’ll do just isn’t me. I’m striving for perfection.” He reveals he dreams of creating a monument “like those in Trafalgar Square or Nelson’s Column.”

Author Ralph Waldo Emerson famously wrote “it’s not the destination, it’s the journey” and although he died in 1882, he could have been talking about Ryan.

Ryan’s career will certainly outlive that Transit van, navigating bumps in the road in his own way and with plenty of humour.

There will be stories to tell – in a Yorkshire accent, of course.

Ryan can be found on Instagram @rjjsculptor

Clare with Ryan