The time of tests : Density

Led by Europe, more tests are being devised all the time to try to evaluate stone. In this column Barry Hunt explains the tests and discusses what the results show… and what they don’t. This time he looks at density.

Like the water absorption test discussed in this column in May, the density test is a simple and versatile test that can provide rapid and useful information. However, to confuse matters there are different types of density that may be determined.

In its most simple form, there is dry density, which is the weight of the dried stone divided by the volume it occupies. This can be determined in a matter of seconds if the stone has a regular shape such as a cube.

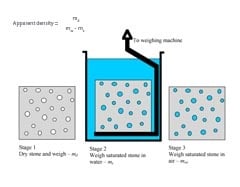

The apparent density is the most commonly determined value (see Figure 1). This involves immersing the stone in water until it is saturated then weighing it while it is still immersed.

The apparent density determines the weight of stone per unit volume minus the voids within the stone. The size of space water can enter has a limit of around 0.005mm under normal pressure, so the density value is not absolute.

When undertaking the apparent density test you can take the stone out of the water and weigh it to determine the saturated density. Another variation is saturating the stone under vacuum to get the water into more of the micropores.

The absolute, or real density can be determined by crushing the stone to dust so that there are no physical voids or pores. A measured amount of the crushed stone is added to water within either a pycnometer or Le Chatelier volumenometer. The real density is determined by either the increase in weight or the increase in volume, respectively.

Small amounts of material can be used, which can be useful when there is a lack of material available. Most other tests are specimen hungry.

Density values are typically given in terms of the mass per unit volume, with the most common units used being kilograms per cubic metre. However, density values can also be given as a ratio relative to the density of water that has a nominal value of 1.

In Europe, the standard for the test is EN 1936. In America it comes under ASTM C97. Both are basically the same, although there are differences in specimen size and number.

The test method may vary when it comes to slate and other thinly laminated and cleaved stones that are typically used in sheet forms, so cube specimens might not be available.

Most stones have a range of density values. If tests deliver values outside the expected range they might indicate, for example, a change in quality of the stone or the presence of a significant proportion of heavy minerals.

However, the most practical use for density values is to determine reasonably accurate weight estimates of masonry units for handling purposes. When buying large blocks of stone, knowledge of the density can be used to ensure you are not paying over the odds.

The density value can also be useful when assessing the quality of a given stone type – say, limestone. Lower density typically suggests decreasing durability as it usually suggests increasing porosity. But this is not always the case and, as always, density test results should not be used in isolation.

The American standards for dimension stone provide a number of minimum limits for different types of stone. In Europe there are no limits and values just have to be declared when required without further explanation.

There is little that can go wrong with the density test because of its simplicity. Only operator error and / or incorrectly calibrated or insufficiently accurate weighing equipment can lead to potentially seriously misleading errors. Variations can arise due to location, height above sea level and the temperature, but they are minor.

Please note: The captions for the two diagrams in last month’s column were the wrong way around, the three-point caption was on the four point test and vice versa.

Barry Hunt is a Chartered Geologist and Chartered Surveyor who has spent 20 years investigating issues relating to natural stone and other construction materials. He now runs IBIS, an independent geomaterials consultancy undertaking commissions worldwide to provide consultancy, inspection and testing advice. Tel: 020 8518 8646

Email: info@ibis4u.co.uk

The advice offered in answer to readers’ questions is intended to provide helpful insights but should not be regarded as complete or definitive. Professional advice should always be sought in respect of each specific stone-related issue.

n May, the density test is a simple and versatile test that can provide rapid and useful information. However, to confuse matters there are different types of density that may be determined.

In its most simple form, there is dry density, which is the weight of the dried stone divided by the volume it occupies. This can be determined in a matter of seconds if the stone has a regular shape such as a cube.

The apparent density is the most commonly determined value (see Figure 1). This involves immersing the stone in water until it is saturated then weighing it while it is still immersed.

The apparent density determines the weight of stone per unit volume minus the voids within the stone. The size of space water can enter has a limit of around 0.005mm under normal pressure, so the density value is not absolute.

When undertaking the apparent density test you can take the stone out of the water and weigh it to determine the saturated density. Another variation is saturating the stone under vacuum to get the water into more of the micropores.

The absolute, or real density can be determined by crushing the stone to dust so that there are no physical voids or pores. A measured amount of the crushed stone is added to water within either a pycnometer or Le Chatelier volumenometer. The real density is determined by either the increase in weight or the increase in volume, respectively.

Small amounts of material can be used, which can be useful when there is a lack of material available. Most other tests are specimen hungry.

Density values are typically given in terms of the mass per unit volume, with the most common units used being kilograms per cubic metre. However, density values can also be given as a ratio relative to the density of water that has a nominal value of 1.

In Europe, the standard for the test is EN 1936. In America it comes under ASTM C97. Both are basically the same, although there are differences in specimen size and number.

The test method may vary when it comes to slate and other thinly laminated and cleaved stones that are typically used in sheet forms, so cube specimens might not be available.

Most stones have a range of density values. If tests deliver values outside the expected range they might indicate, for example, a change in quality of the stone or the presence of a significant proportion of heavy minerals.

However, the most practical use for density values is to determine reasonably accurate weight estimates of masonry units for handling purposes. When buying large blocks of stone, knowledge of the density can be used to ensure you are not paying over the odds.

The density value can also be useful when assessing the quality of a given stone type – say, limestone. Lower density typically suggests decreasing durability as it usually suggests increasing porosity. But this is not always the case and, as always, density test results should not be used in isolation.

The American standards for dimension stone provide a number of minimum limits for different types of stone. In Europe there are no limits and values just have to be declared when required without further explanation.

There is little that can go wrong with the density test because of its simplicity. Only operator error and / or incorrectly calibrated or insufficiently accurate weighing equipment can lead to potentially seriously misleading errors. Variations can arise due to location, height above sea level and the temperature, but they are minor.

Please note: The captions for the two diagrams in last month’s column were the wrong way around, the three-point caption was on the four point test and vice versa.

Barry Hunt is a Chartered Geologist and Chartered Surveyor who has spent 20 years investigating issues relating to natural stone and other construction materials. He now runs IBIS, an independent geomaterials consultancy undertaking commissions worldwide to provide consultancy, inspection and testing advice. Tel: 020 8518 8646

Email: info@ibis4u.co.uk

The advice offered in answer to readers’ questions is intended to provide helpful insights but should not be regarded as complete or definitive. Professional advice should always be sought in respect of each specific stone-related issue.