The time of tests : Petrography

Led by Europe, more tests are being devised all the time to try to evaluate stone. In this column Barry Hunt explains the tests and discusses what the results show… and what they don’t. This time he explores petrography.

I have left petrography to the last of my short introductions to the current European Standard tests, but it is undoubtedly the most useful.

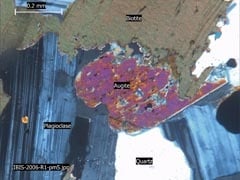

Petrography is the process of describing stone, which can be achieved by any available means – visual inspection, microscopy,

X-ray diffraction and other techniques. Looking through a microscope is the most common and useful process.

When undertaking any of the other stone tests the petrographic name of the stone is required and can only be determined in accordance with EN 12407.

But petrography is so much more than just the naming of a stone when the examination is carried out by someone experienced in the many issues that can affect stone.

What the trade calls ‘sandstone’ covers a range of quartz-rich minerals, which might be classified as quartzite, orthoquartzite, arenite, quartz arenite, quartzitic sandstone, psammite and, if a bit gravelly, also rudite and psephite.

With some very subtle changes in composition and texture there are a wealth of other names that could be applied to a sandstone.

Then there are the terms such as flagstones and sarsens applied by by the industry. Geology and the naming of stone are rarely straightforward.

How does classification happen?

Well, the petrographer, who is usually a geologist by training, will determine the types of minerals present, their respective proportions, the size, shape and interlock of the crystals and grains, the presence of any matrix or cement and the occurrence of any alteration either from geological processes or surface weathering.

The presence of bedding, lineation, spotting, veining, jointing, cleavage, and many other textures or structures are also determined. There are various techniques available to assist, the main one being the creation of thin-sections, which will be covered in the next issue.

A geologist can use petrographic information to create a three dimensional picture of the original depositional environment and then add to this the rock forming processes of burial, deformation and uplift under different heating and pressure regimes that have been applied over the millennia to create the stone in front of them.

This knowledge allows the geologist to predict the likely characteristics of the stone – such as the compressive and flexural strength, density, absorption, porosity, slip and abrasion resistances, acid and thermal cycle resistances and the likely resistance to frost – basically, all the main properties required by the European Standard tests.

If you have, say, 10 candidate stones you are trying to choose between for a project, the choice can be narrowed down by a geologist who has been briefed on the design and potential use of the stone in a matter of minutes. You do not need to run all the stones through the full gamut of tests.

The stones selected as a result of the petrographic examination can just have their strength and absorption properties determined as a check before proceeding.

Similarly with new stone resources. Petrography provides the potential to save a considerable amount of time and money on testing.

Many of the unusual problems I have written about in this column previously have been resolved by considering the petrography of the stone in question. Relating stone properties to the environment of use, the design, construction and maintenance, can only be carried out expertly when there is a good understanding of the stone.

Knowing about the action and interaction of the stone with other construction materials is also essential, particularly the use of cements and adhesives.

For a good introduction to the petrography of building stones I can recommend ‘Geomaterials Under the Microscope’. A better understanding of the wonderful material that is stone will provide you with the opportunity to avoid many potential issues and make better use of this valuable resource.

Reference

Ingham, J P (2010). Geomaterials Under The Microscope, A Colour Guide. (ISBN: 978-1-84076-132-0) Manson Publishing Ltd, London.

Barry Hunt is a Chartered Geologist and Chartered Surveyor who has spent 20 years investigating issues relating to natural stone and other construction materials. He now runs IBIS, an independent geomaterials consultancy undertaking commissions worldwide to provide consultancy, inspection and testing advice. Tel: 020 8518 8646 Email: info@ibis4u.co.uk. The advice offered in answer to readers’ questions is intended to provide helpful insights but should not be regarded as complete or definitive. Professional advice should always be sought in respect of each specific issue.