War memorials : Remembering the war to end all wars

Irish company Stone Source, supplied by McKeon Stone, gets a stark reminder that conflicts continue as it builds new World War I memorials in Abuja and Dublin.

The building of new memorials to the casualties of World War I in Abuja, the capital of Nigeria, and Ireland’s Glasnevin Cemetery, Dublin, by Irish company Stone Source have proved to be stark reminders that World War I does not quite live up to its epithet as the ‘war to end all wars’.

The fact there are memorials to World War I in so many countries emphasises what a truly global conflict it was. But armed guards in Abuja and the dedication of the memorial in Dublin that was to have involved French President François Hollande disrupted by a terrorist attack in Nice, emphasise the continuation of international conflict.

The fact there are memorials to World War I in so many countries emphasises what a truly global conflict it was. But armed guards in Abuja and the dedication of the memorial in Dublin that was to have involved French President François Hollande disrupted by a terrorist attack in Nice, emphasise the continuation of international conflict.

Both memorials were constructed by Dublin-based Stone Source, headed by James McKeon and supplied with stone processed at his quarrying business of McKeon Stone, based at Threecastles Quarry in Kilkenny.

The memorial in Dublin was built of the Irish Blue limestone from the quarry, although the memorial in Abuja is granite.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC), the organisation responsible for ensuring all British service personnel killed in action are commemorated, was behind the new memorial in Abuja, while the French commissioned the memorial at Glasnevin to commemorate the men of the Irish 16th Division who played such a major role in the Battle of the Somme in France in 1916.

James McKeon admits he had reservations about going to Nigeria with a team to construct the memorial there. “Everyone told me not to go,” he told NSS, “but I ignored them, as I usually do.”

Before he asked any of his team to go to Nigeria for the project he and Niall Kavanagh, the Managing Director of McKeon Stone, went to try to establish how dangerous it was.

Originally, James had only bid for the stone supply, but once he had won that contract the CWGC asked him if he would build the memorial. He says what made it not only possible but almost luxurious (in spite of the constant need for the armed guards) was the existence of PW Construction, which has been working in Nigeria for 40 years and has an established enclosed base there. It did the civils ready for the stone construction. James also praises the British High Commission and the Irish Embassy for their help.

The building stone used in the area is granite, but obtaining building materials in Nigeria is unreliable, so James sourced 60 tonnes of Chinese G603 that went to McKeons Stone in Ireland to be worked. It was then shipped in three containers with 8tonnes of sand and 3tonnes of cement under diplomatic immunity so it was actually on site when James and three of his top fixers arrived to build the memorial. “We wanted to have the situation that when we opened the containers we could go to work,” says James.

The focal point of the memorial is a bronze statue of a World War I Nigerian soldier and a water carrier, cast in 1928 for a war memorial that had previously stood in Lagos when it was the country’s capital. The memorial had been taken down in the 1960s when Nigeria became independent and the statue had remained in storage since then. The CWGC took it out of storage to use on the new memorial.

Although the circumstances were unusual, the build was relatively straight forward. The finished memorial will be the focus of Armistice Day ceremonies in the country in November.

By contrast, James says the memorial in Dublin “was the most challenging one I have ever been involved in”.

In 2014 James McKeon had built Ireland’s first Cross of Sacrifice memorial in Glasnevin cemetery. Now he was asked by the French to build a Cross of Ginchy memorial next to it using the same Irish Blue limestone from Threecastles Quarry.

The complexity came about because the memorial was designed by sculptor Patrice Alexandre of the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, a fine arts institution in Paris.

The Cross of Ginchy is a memorial to almost 5,000 Irish soldiers of the 16th Irish Division who died at Ginchy in the Battle of the Somme. The original Cross of Ginchy is a Celtic cross fashioned by the survivors of the battle in memory of their fallen comrades from beams taken from the roof of a barn on the battlefield. It stood in Ginchy for about a decade before being repatriated to Ireland, where it is preserved. It was brought out into the War Memorial Gardens in Dublin for The Queen’s visit in 2011.

Patrice Alexandre’s idea was to reproduce that cross in Irish Blue limestone.

A path made of the outer crust of blocks of the stone leads up to the memorial. On either side of it are raw blocks of the stone with cast bronze helmets on top of them representing those warn by the Irish, French and British soldiers of the Allied Forces involved in the battle.

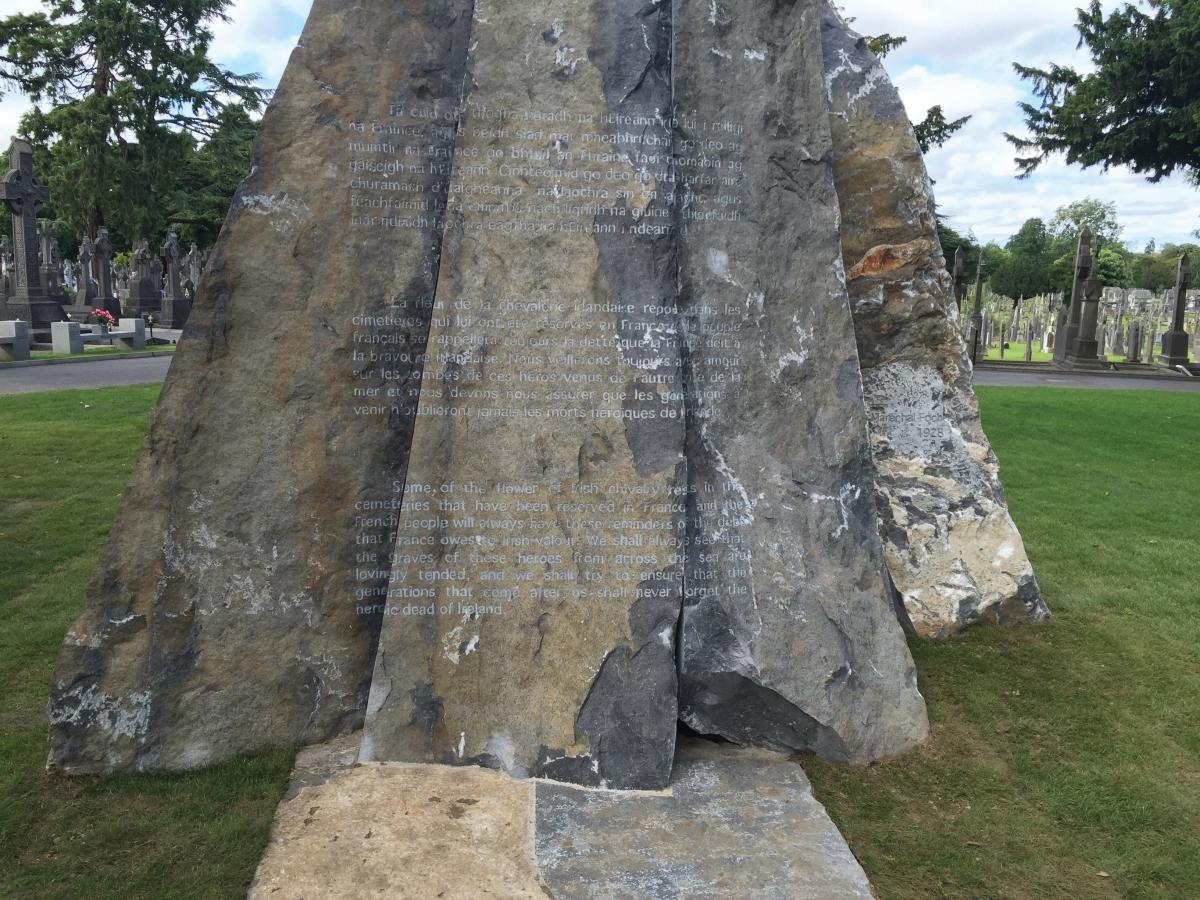

But what made the memorial particularly difficult to produce is the inscription. The stone Cross of Ginchy rises out of shards of rough hewn limestone and Patrice Alexandre wanted the inscription to go across the different pieces of stone. It means you can only read the whole of the inscription when you stand at one particular vantage point 5m back from the stone, marked by a piece Kerry Red Marble.

But what made the memorial particularly difficult to produce is the inscription. The stone Cross of Ginchy rises out of shards of rough hewn limestone and Patrice Alexandre wanted the inscription to go across the different pieces of stone. It means you can only read the whole of the inscription when you stand at one particular vantage point 5m back from the stone, marked by a piece Kerry Red Marble.

In order to get the inscription just right, James McKeon hired a projector and erected a dark tent around the memorial to project the words on to it from the exact spot where it can be read. Sandblast tape was put on to the stone and the letters cut into the tape and then sandblasted on to the stone.

The inscription is taken from the 1928 tribute to Irish soldiers who died in the First World War by Marshal Foch. It is written in Gaelic, French and English. It includes the line: “Some of the flower of Irish chivalry rests in the cemeteries that have been reserved in France, and the French people will always have these reminders of the debt that France owes to Irish valour.”

James says: “It’s the most extraordinary piece of monumental sculpture I have ever seen in my life.”

He praises the contributions of Irish sculptor Phil O’Neill, now 72, lettercutter Aileen-Anne Branigan and emerging artist Melissa Donagher.

Further information…

The Abuja Memorial is located within the National Military Cemetery on the Northern side of the Airport Road (Umaru Musa Yar’Adua Road) approximately 10km from the centre of Abuja. The National Military Cemetery is permanently staffed by a detachment of the Nigerian Military. They are responsible for the control and security of the site, which is open to the public during daylight hours only by prior arrangement with the Department of Veteran Affairs.

The Abuja Memorial is located within the National Military Cemetery on the Northern side of the Airport Road (Umaru Musa Yar’Adua Road) approximately 10km from the centre of Abuja. The National Military Cemetery is permanently staffed by a detachment of the Nigerian Military. They are responsible for the control and security of the site, which is open to the public during daylight hours only by prior arrangement with the Department of Veteran Affairs.

In 1932 the Lagos memorial was erected in the Idumota area of Lagos to commemorate the 947 Nigerian casualties of the Inland Water Transport, Royal Engineers and Nigeria Carrier Corps who died during the 1914-18 War, whose graves could not be maintained or located.

A similar memorial, known as the Nigeria Memorial, was erected in 1962, at the same location, to commemorate the 1158 Nigerian casualties of the 1939-1945 War, whose graves had also been lost or could not be maintained.

In 1978 the two memorials were relocated by the Nigerian Government to form part of a new Nigerian National Memorial in Tafewa Balewa Square, Lagos. In 1989, this new structure was dismantled by the Nigerian Government as they planned to build a new National Memorial in their new capital, Abuja. The Commission's new Abuja Memorial finally completes this process.