Waterjets & Robots : It’s neither a dream nor a nightmare, but the reality of stone processing

There have been lots of reports this year of robots replacing people in the workplace. Whether you see that as utopia or dystopia or simply part of a continuum from the time man first picked up a stone and used it as a tool, there was certainly evidence of it in the stone industry this year.

It does not quite constitute artifical intelligence yet, but the latest machinery for processing stone in both its natural and engineered forms is pretty clever stuff.

For many years now it has been less about the hardware and more about the software that controls CNC machinery. That remains true, but now it is also about digital communications connecting the different aspects of production and providing feedback to avoid unexpected bottlenecks and breakdowns and expensive unplanned disruption of production and distribution.

As we saw in the annual review of equipment in Natural Stone Specialist’s September issue, it goes under the name of Industry 4.0, or i4.0. It was evident at Europe’s international Stone+Mac exhibition in Verona, Italy. And nowhere more so than on the stand of T&D Robotics, which is represented in the UK by machinery agent Roccia Machinery.

“Industry 4.0 in front of our eyes,” said T&D. It said on its stand that this enabled a previously unimaginable optimisation of production.

Even more impressive was that the production line on show was just one of four of T&D’s robotic solutions that was destined for a company in the UK – Natural Stone Surfaces.

According to The Boston Consulting Group, a business advisor, the potential impact of the UK embracing Industry 4.0 could be productivity improvements of as much as 5-8%, giving the country a long-term competitive advantage. Boston emphasises how important that will be in a post-Brexit economy, especially as UK productivity currently lags behind that of the leading industrialised nations.

Boston says if UK manufacturing as a whole leads the world in this next stage of the digital industrial revolution, it could see annual real growth of 1.5-3% – even more if there were to be a clear national strategy to support the UK’s industrial digital transformation.

T&D said the Lapisystem-based production line it was showing in Verona was capable of automatically loading any kind of slab, turning it into a kitchen top and palletising it ready to be shipped without being touched by a human hand.

The company said: “We refer to plants where several robots co-operate to achieve a common goal, capable of using and communicating with traditional machines. Thanks to remote control, via internet connection, the whole line is played in a simulator, getting real-time diagnostics on the efficiency of every small detail.”

Design is in three dimensions, perhaps from 3D scanned files or templates, using CAD-CAM. Modelling time is proportional to the complexity of the object to be manufactured – a simple vanity top takes only a few minutes.

The tool path is developed by the operator into a computer-aided manufacturing (CAM) environment, using a tools library or pre-set macro processing.

The Lapisystem then shows a 3D simulation of the complete working process, enabling the operator to verify that everything is correct. If necessary the operator can intervene to improve some aspects. Having completed the simulation, the operator sends the program to the robot and it begins working.

The four Lapisystems going to Natural Stone Surfaces’ 2,400m2 state of the art factory, are intended to enable the company to continue its impressive growth rate since starting with three people in 2001.

In the past decade it has developed into not just one of the UK’s leading stone manufacturers, but one of Europe’s, with a customer base that includes many kitchen studios across the UK and into mainland Europe. The company puts its success down to attention to detail. It says: “We are proud to work with some of the industry’s most prestigious kitchen manufacturers and interior designers, all of whom demand an efficient service at a competitive price.”

The ABB Foundry Plus 2 robot arm going to Natural Stone Surfaces via Roccia in the UK was developed to protect robots in the harshest environments of a metal foundry. If it can cope with the coolants, lubricants, and metal spits of a foundry it should survive the conditions encountered in stone processing.

Robots protected by Foundry Plus are completely sealed from base to wrist, protecting joints and flange. The motors are also sealed and the combination of aluminium chromation and steel primer protection underneath a two-component epoxy paint should keep rust away.

And the optional Foundry Plus 2 protection even improves on that, enabling the robot to withstand high-pressure steam washing and making it highly corrosion proof, so it is IP67 compliant. The result: less maintenance and a longer life.

Robot arms have been used in manufacturing for a long time. Their introduction to the stone industry was not entirely successful, but increased computing power and the continued development of the software that drives them has made them more useful. One of the first UK stone companies to get a robot was J Rotherham. It was involved in a lot of the development and now uses three routing robots and one it uses for cutting, including waterjet cutting.

Inevitably, as more people decide to invest in robotic arms, more people decide to make them. Thibaut introduced its version some years ago and at Marmo+Mac in September, Donatoni Macchine introduced its robot, which sells under the name of Cyberstone CR1.

Donatoni Macchine these days sells its range of mostly bridge saws in conjunction with CNC machine company Intermac. This year Intermac bought Montresor so it could offer the full complement of its own CNC workcentres and waterjets, Donatoni bridge saws and Montresor edge polishers. It has now also got the CR1 into the bargain.

Donatoni Macchine these days sells its range of mostly bridge saws in conjunction with CNC machine company Intermac. This year Intermac bought Montresor so it could offer the full complement of its own CNC workcentres and waterjets, Donatoni bridge saws and Montresor edge polishers. It has now also got the CR1 into the bargain.

Donatoni Macchine describes the Cyberstone CR1 as a robot for “automation and production integration”.

The theme of the once again combined Intermac and Donatoni stand at Marmo+Mac was ‘Think Forward’, which was another Industry 4.0 message of using software to capture the opportunities of digitised, interconnected manufacturing.

Although we tend to think of robots in terms of Kuka and ABB arms, any CNC is basically a robot and Italian company Helios has had a rethink about what that means with its Star Series, which puts the spindle on a tower. This, the company says, combined with its Helios Galaxy Stone software enables the Star to be fast, precise and reliable.

The tower structure gives it an extensive and stable Z axis reach for producing work from large blocks of stone clamped on a turning table with slats.

The turning table enables the Star to process the full 360º around a block for making features such as statues, capitals, columns and portals, although it can also carry out processes of milling, sculpturing, engraving and lettering.

And with the optional lathe, it is possible to carry out horizontal turning.

One of the drivers of developments in CNC machinery is the latest generation of engineered stone products, which are a mixture of porcelains and sintered materials that seem to be settling down under the generic term of UCS (ultra-compact surfaces). They have presented processors used to cutting slabs of granite and engineered quartz with some difficulties, which diamond tool makers continue to work to overcome more effectively.

Some processors have decided the solution is to use waterjet cutters, especially as they now come in five-axes versions that can produce accurate 45º (or other angle) mitres.

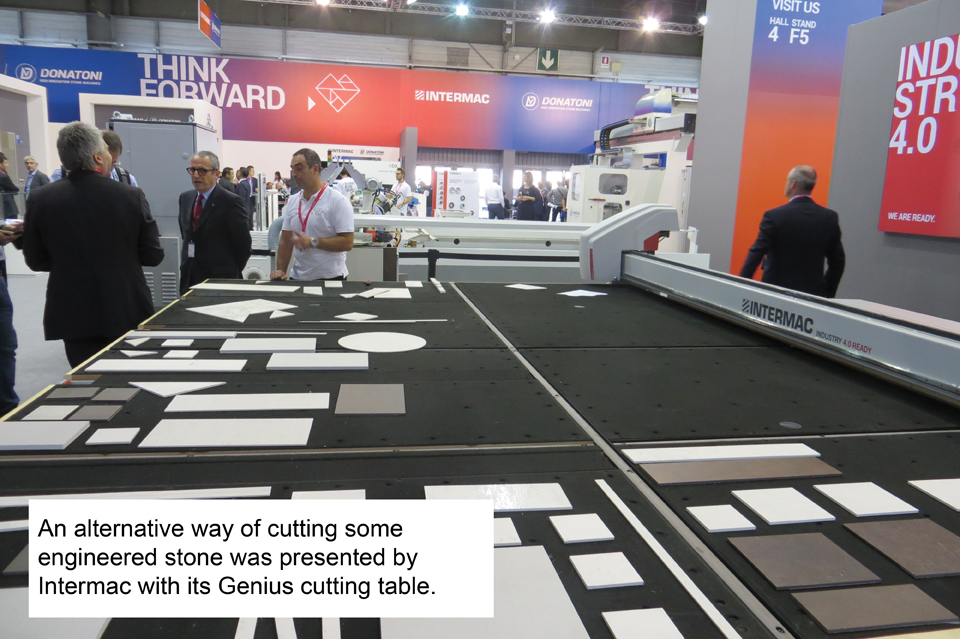

But at Marmo+Mac, Intermac offered another solution. Instead of fighting against the materials’ tendency to snap, it has harnessed that tendency with the Genius RS-A cutting table.

Because UCS and porcelains behave somewhat like glass, Intermac has tried using some of the glass processing machines made by the company to cut the new sheet materials. The cutting table provides an answer, although it can only work on thin materials. It can cut straight lines in material up to 12mm thick and curves in material up to 3mm thick.

It works like a diamond glass cutter, scoring the surface so the sheet can be snapped. The snapped material might then be put through a double edge polisher, also from the glass industry, that finishes two parallel edges simultaneously.

Whether that will catch on for stone processors remains to be seen, especially with Lapitec already available in 30mm thick slabs and Dekton promising to have 30mm slabs in the New Year.

For an increasing number of companies, waterjets remain the preferred solution. That has led to a proliferation of them from the manufacturers.

Waterjets have been on a slow burn in the UK stone industry for many years, with one or two companies investing in them because they saw the potential for precise cut-outs and inserts – putting company logos into floors and plaques, for example.

Lately, though, they have become a must-have machine for many fabricators as the range of materials being processed has grown. The attraction of a waterjet is that any material can be cut without having to change the tools, reducing make-ready time.

Lately, though, they have become a must-have machine for many fabricators as the range of materials being processed has grown. The attraction of a waterjet is that any material can be cut without having to change the tools, reducing make-ready time.

Most people buying waterjets have found them relatively expensive in use compared with blade cutting. They are slower, need abrasives, and require fairly frequent replacement of the jet focuser and the bars that support the work, which get cut along with the workpiece.

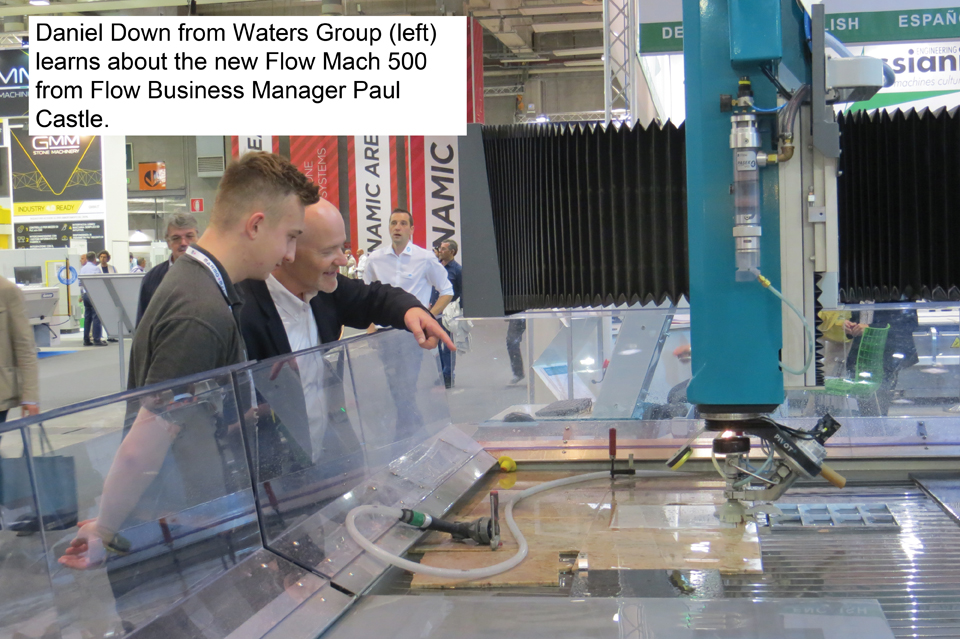

The American company Flow was one of the first to develop the potential of waterjets for stone processing in the UK and has teamed up with one of the stone industry’s major machinery, tools and equipment agents, the Waters Group, to help it reach the sector.

Flow exhibited on the Waters Group stand at the Natural Stone Show in London this year and at Marmo+Mac was in turn supported by its UK agent as it introduced the Mach 500 to European stone processors. It hailed the machine as “a quantum leap in reliability and productivity”.

FlowXpert 3-D CAD/CAM software, with 3-D modelling capability, calculating optimum cutting paths, and the recently introduced Compass five-axes contour following and collision sensing solution mean the Mach 500 has 15-30% shorter cycle times than Flow’s best-selling Mach 3b.

Flow has been making waterjets for 40 years and this is its 12th generation system. “With each generation we have further improved major components and achieved ongoing increases in accuracy and cutting speed,” says Claus Herting, Managing Director of Flow Europe.

Intermac is another CNC machinery company that has now become an established supplier of waterjets to stone companies. It was showing its Primus 402 in Verona this year. Denver is another, represented in the UK by Accurite. In Verona it showed its Aqua waterjet.

Omag waterjets, sold in the UK by D Zambelis, use 29kW KMT waterjet pumps to produce a working pressure of 3,800bar.

Axes X and Y are powered by brushless digital motors driving pinions on hardened helical racks. Linear sphere guides achieve high accuracy movement for precise, fine cuts. The Z axis is equipped with a spherical recirculating screw.

They use Watertag (Taglio) CAD/CAM software developed specifically for waterjets. In conjunction with MagicTool, this provides complete control, allowing nesting and optimisation for inclined cuts, such as 45º mitres for drop fronts.

Abrasive consumption is minimised by optimising control of all the system’s parameters and, like most waterjets now, the Omag has a probe that maintains a fixed distance between the focuser and the slab to make sure the cut is consistent, even if the surface is not perfectly flat. That also safeguards the focuser.

Breton, which this year opened its own office in the UK in Cambridge, splitting with Carl Sharkey’s LPE Group, which has represented it through the separate company of Breton UK, showed a Classica waterjet at the Natural Stone Show in London this year.

It has not built its own waterjet but has teamed up with another Italian company, Waterjet Corporation, to exclusively supply the stone industry. Waterjet Corporation has been making waterjets since 1991 and its machines have a reputation for being precise, powerful and fast, especially with the option of a pump that delivers a pressure up to 6,200bar.

For a decade before the Waterjet Corporation agreement, Breton had supplied a waterjet combined with a disc cutter on the same machine in its CombiCut, although it has attracted few customers among UK and Irish stone companies.

But, again, ever increasing computing power and the wider range of products being cut has encouraged companies to take a second look. The idea of a machine that can switch from discs to water cutting on the same job to improve productivity starts to look attractive.

And with more processors buying them, other companies have come up with their own versions of the concept. Cobalm, represented in the UK by Waters Group, is one of them. At Marmo+Mac this year it showed the Integra Jet, which is its version of the dual action bridge saw cum waterjet.