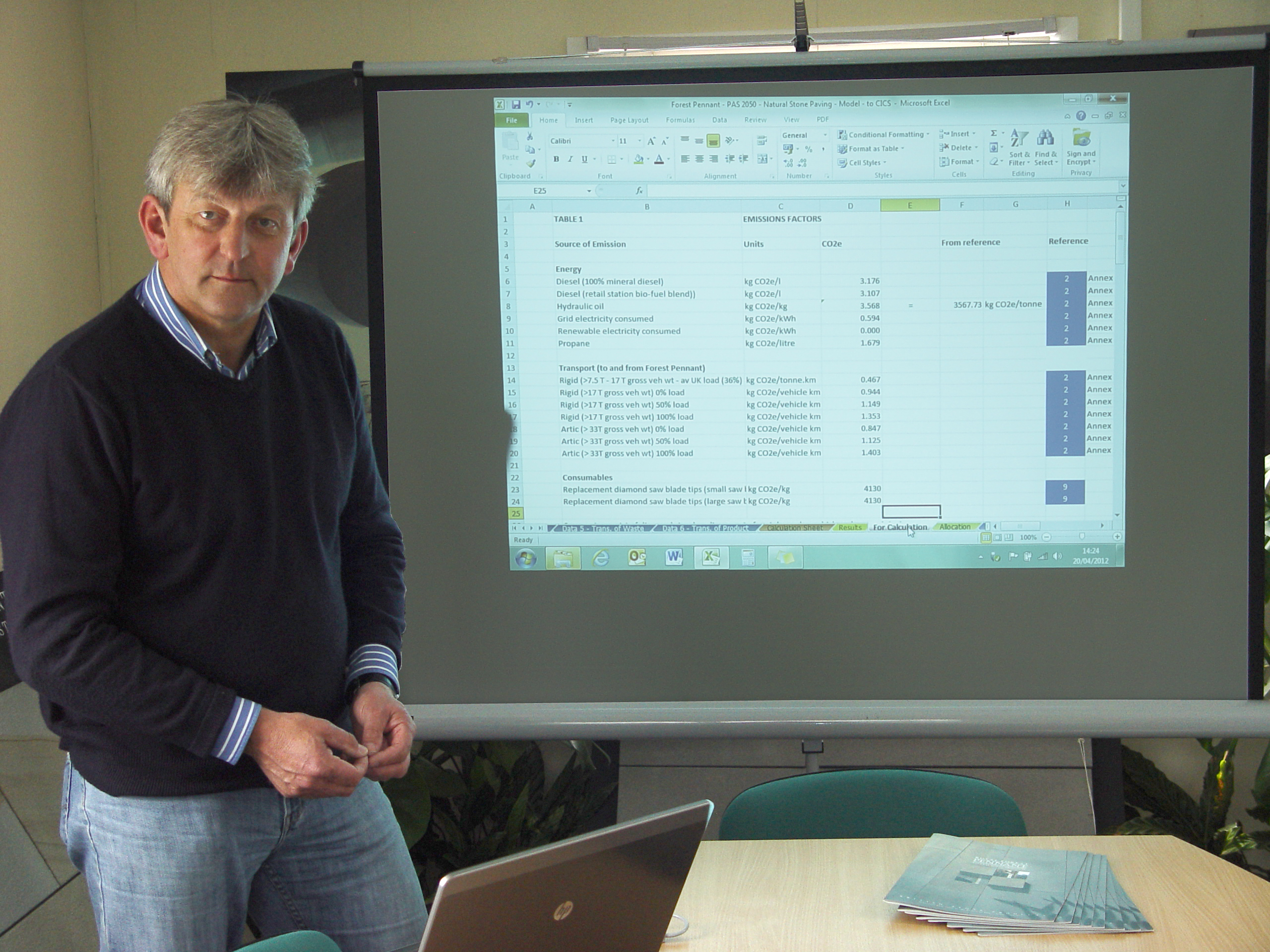

Forest Pennant has spent thousands of pounds determining the carbon footprint of its paving products in order to achieve PAS 2050 certification. Now you can use the spreadsheet devised for Forest Pennant to calculate the carbon content of your products.

There is quite a lot of work involved in gathering all the information required to work out the carbon footprint of stone, but at least there is now a spreadsheet available that can help you to do it.

It was produced for Forest Pennant’s work on PAS 2050 carbon footprinting of its stone from the Forest of Dean but Managing Director Nick Horton has decided to make it available to the whole industry. It is specifically for stone paving, but could be adapted as a guide for other uses of stone. It is identified as the CARBON CALCULATOR. It can be downloaded below.

Nick says: “I am constantly being challenged by my customers to meet greener criteria, and as an industry we need to react and meet these demands head-on. This is why I put Forest Pennant through this process and why I am now offering up this model to the industry.

“In order to be competitive and be measured against others in the industry, be it stone or concrete, I feel that all manufacturers, such as myself, should get rated!

“The end game isn’t just about enabling our customers to accurately compare products based on their environmental credentials but also, ultimately, it makes financial sense.”

The Forest Pennant figures have been removed from the Carbon Calculator on the website so you can add your own, but all the relevant conversions are included in the spreadsheet – grid electricity at 0.5246kg of CO2 equivalent emissions per kilowatt hour, for example, and diesel at 2.6676kg of CO2 equivalent per litre.

The ‘equivalent’ converts other greenhouse gases (GHGs) to the equivalent amount of CO2 to create a single unit to make the sums simpler, although if you look at the detailed spreadsheet of conversions produced by Defra in conjunction with DECC (Department for Energy & Climate Change) it is anything but simple.

But you don’t have to look at it. You can use the Forest Pennant Carbon Calculator and just enter the quantities for your own business.

Forest Pennant used its figures from the calendar year 2010 (which covered two financial years, complicating the collation of the data) before it had installed a hydroelectric generation plant at its works. It is currently inputting figures from 2011, which will show the benefit of the hydroelectricity.

But it is not only green electricity generation that will have reduced the company’s CO2 emissions and, with it, costs – because carbon auditing is not just an academic exercise. CO2 emissions represent energy used and knowing which parts of your operation account for what proportion of your energy use can identify areas where savings can be made.

And the results will probably produce some surprises. One of the biggest for Forest Pennant was the contribution to the carbon footprint of the company’s paving from the industrial diamonds used in sawing it.

Obtaining a figure for the saw segments, with their copper, iron and tungsten, as well as diamond, was not easy either, because the saw-makers like to keep secret the exact recipes of their segments and did not know or were reluctant to share the encapsulated carbon information.

When a figure was calculated, it turned out to be huge, largely because of the energy required to produce the heat and pressure necessary to make the diamonds. The saw segments accounted for more than half the 47.5kg of CO2 equivalent encapsulated in each square metre of 50mm thick Royal Forest Pennant paving as it leaves the factory.

There were other surprises. The company discovered it used 77,000 wax strips at 10p each and 26,000 polystyrene strips at 40p a strip for packaging in 2010 without even thinking about it. They were simply purchased as necessary. In both cases the numbers used have been halved.

Shrink wrapping produced another saving. It had previously all been printed but by using unprinted shrink wrapping except on top, more savings were achieved.

Even with the hydroelectricity now being generated at Forest Pennant’s factory at Park End, near Gloucester, the company needs diesel generators to power its big primary saws. But it has been running two generators because one could not get the saws started on its own. Adding an inverter to produce a soft start has enabled the saws to run off one generator, keeping the other in reserve in case of emergencies (although they are alternated to keep them both serviceable). That has reduced the diesel used for processing by 26,000 litres a year.

Achieving these savings has not been without its costs. The standard PAS 2050 is available free from British Standards Institution and can be downloaded from the BSI website. But that was the only easy and free part of the exercise.

Apart from the investment in the soft start for the saws and the hydroelectricity generation, simply gathering the information (“My poor admin staff,” says Nick Horton) and organising it into a useable format was not cheap. It involved employing consultants David Dowdell and Clive Onions, both formerly with Ove Arups, to make some sense of it all.

Then the information gathered and collated had to be verified. Forest Pennant got that carried out by CICS, part of CERAM, because it charged £3,000 rather than the £8,000 the Carbon Trust wanted. Nick Horton says the whole process cost Forest Pennant about £8,000 in payments to consultants.

Using the Forest Pennant Carbon Calculator can save you some of that price, but Nick Horton does strongly recommend getting your figures verified and audited to achieve PAS 2050 certification, so they stand up to scrutiny and can justifiably be quoted and, ultimately, used in the specification process. The more people who do it, the greater the legitimacy of the process and the value of the standard to the stone industry as a whole.

Nick says carrying out the analysis has changed his outlook. “I have actually, personally, taken a sea change in my opinion about this.”

And he can see ways of making Forest Pennant even greener – by mining it rather than opencasting, for example, so it is no longer necessary to remove at least 10m of overburden to reach usable stone. Extracting the stone currently accounts for 9kg/m2 of 50mm stone, which mining would significantly reduce.