Government schemes to revitalise the housing market are working but there is a North/South divide being felt by stone suppliers.

The Government’s housing Help to Buy scheme, the second part of which was introduced last month (October) three months ahead of schedule, seems to have injected a further degree of confidence into the market. It was already buoyed up by the Funding for Lending initiative that has seen more money going to mortgages and a continued fall in mortgage interest rates – Nationwide has one at just 1.94%.

The first part of the Help to Buy scheme, equity loans, began in April. This scheme allows buyers with a minimum 5% deposit to take out an equity loan of up to 20% of the value of a new build property priced at a maximum of £600,000.

This is distinct from the mortgage guarantee part of the Help to Buy scheme, which began last month and under which the government underwrites 15% of the value of mortgages on new and existing properties, again with a maximum value of £600,000 and a minimum 5% deposit.

The Home Builders Federation (HBF) has reported that 4,000 new homes were reserved during the first two months of the equity loan scheme – that is approximately 20% of all demand for new homes prior to the scheme. HBF also reports that some of its members have revised their projected build levels upwards due to the scheme.

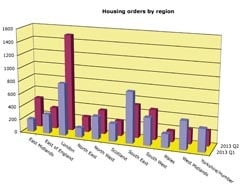

That is confirmed by the number of properties with approved planning permission, which increased 49% between Q2 2012 and Q2 2013, suggesting that home builders are increasingly optimistic about future demand.

A month after the mortgage guarantee part of the Help to Buy scheme was started the Conservative Party (rather than the Coalition Government) announced:

- More than 2,000 people had been accepted in principle for a Help to Buy mortgage

- £365million worth of mortgages were being processed under the scheme

- A third more houses were being built than at the same time last year.

Most of the take up of the Help to Buy scheme so far has been by first-time buyers and the properties they are buying are not likely to be the sort of place that incorporates a lot of stone.

Nevertheless, the increase in demand for property that is not yet being equalled by an increase in supply is having the inevitable consequence of increasing prices across the board. The housing price index for the whole of the UK has this year gone above the previous highest point in January 2008, before the credit crunch brought it crashing down by 14%.

The latest price index figures available are for September. They show a big difference in prices across the regions. In England prices fell slightly from their all-time record level in August, but were still 0.8% higher than the previous peak in 2008.

In Northern Ireland, by contrast, the September figure is 50.8% below its peak, which was in August 2007. The index for Scotland is also well below its peak, which occurred in June 2008. It is now 7% below that. In Wales, prices were 6.2% below their peak in January 2008.

Taking into account the falls and the rises, the average UK mix-adjusted house price in September was £245,000.

That has led some people to be concerned that a housing bubble like the one that led to the credit crunch and the current level of austerity is re-emerging in England, and even more specifically in London, where prices rose another 9.4% in the year to September. Although, by contrast, in the North East they fell 0.3%.

Of course, higher prices do tend to favour the use of better materials, which can only be good news for the stone industry, although the quarries supplying building stone do reflect the North/South divide in the fortunes of the housebuilding industry.

In general, the economic downturn and the extended recession in the construction industry has not hit the UK’s stone producers as badly as it has some building material suppliers.

The loss of 100,000 new houses being built each year when there were 250,000 built in the best of times (in round figures) is inevitably going to be felt by anyone supplying that market, and hardly anybody reports that volumes of sales have increased. But for many stone suppliers the products demanded changed, so there was less random walling wanted but more high value ashlar and architectural features.

In the past five years there have been a surprisingly large number of modern mansions and country houses built in the desirable parts of the country and the people building them have tended to want to use local materials that match the existing buildings responsible for giving areas their unique characters.

Although there are no official figures for the production or sale of indigenous stone in the UK, reports from the producers certainly suggest they have not been hit by the levels of decline faced by stone importers and the brickmakers – and bricks would have been used for most of the houses not built.

In fact, brick production in the UK has fallen so much in the past five years that as more houses are being built again there is shortage of them. Lead times are being quoted at 20 weeks and suppliers are importing bricks from Europe to make up the shortfall. Suppliers have been warning of a 10% price rise in December. This is all good news for stone suppliers.

“We have definitely seen a pick up in house building and it’s mostly come from the national housebuilders,” says Adrian Phillips, who runs Black Mountain Quarries, just on the English side of the border with Wales in Herefordshire, and the DeLank granite quarry in Cornwall.

The disparity between the prices of most brick and stone as walling has been reducing for many years. With more stone being used by builders, suppliers have been able to benefit from economies of scale of production. But stone walls do still cost more than brick to build and anything that reduces the difference can only benefit the stone companies.

One of the strengths of stone suppliers during the downturn has been their ability to change what they make quickly to respond to the changing requirements of the market. Brickmakers, which are generally orders of magnitude larger than Britain’s quarry companies, have not been able to respond so quickly. They have reduced capacity in the past five years and cannot quickly ramp it up again.

Being small has also helped many stone companies weather the economic storm, because they have not needed to supply the stone for many mansions in order to keep busy. The same is true of housing now that it is picking up. Relatively few schemes using stone can quickly make a difference.

In Cornwall, a 4,500 unit development on Duchee of Cornwall land, similar to the Poundbury extension to Weymouth on the Duchee’s land, has had a significant impact on the DeLank granite quarry’s workload.

“They are not taking vast quantities of our granite each year but it could go on for 25 years,” says Adrian Phillips. “We are supplying stone for the hard landscaping and we’re still chatting about the walls. We would be disappointed if we didn’t get a bit more work there.”

Adrian says he is receiving more enquiries now than for a long time. “There’s definitely a light at the end of the tunnel – as long as its not another train coming in the opposite direction we will be all right.”

Further North it is harder for stone companies to see any light at all. Stamford in Leicestershire is defined by its stone but Stamford Stone Company says it cannot discern any improvement in the market. Russell Stone Merchants in Yorkshire says it has benefitted from an upturn in housebuilding but that with banks still reluctant to lend, much of what is being built is low cost and does not include stone. Director Mark Reid says: “It’s still very, very, very hard.”

Block Stone, based in Derbyshire and one of the biggest dimensional stone quarriers in the UK extracting stone from eight sites, is also working hard to win projects.

Tina Bailey, the Sales Manager of Block Stone, says she had been in Ireland lately, North and South, and before that was in Scotland seeing customers and talking about projects coming up. She says customers are still chasing money and the resulting price wars are causing problems for everyone.

She says too many false dawns have made it difficult to see daylight ahead. “I thought at one point this year we had turned the corner but now I’m not so sure.”