The British Normandy Memorial officially opened on Sunday 6 June, 77 years to the day since D-Day, when the armed forces of Britain and its allies landed on the beaches of Normandy in an operation that marked the beginning of the end of World War II.

The official opening of the Memorial was presided over by the British Ambassador to France, Lord Edward Llewellyn, accompanied by senior French guests.

The ceremony was watched via a satellite link by Britain’s Normandy Veterans, invited to the National Memorial Arboretum in Alrewas, Staffordshire, for the occasion. They did not go to the Normandy Memorial itself because of the difficulty of going to France during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The Royal British Legion and the Normandy Memorial Trust hosted the D-Day commemoration service at the National Memorial Arboretum.

The Royal British Legion’s Assistant Director of Commemorative Events, Bob Gamble OBE, says: “We understand how much it means to the veterans and their families to be in Normandy for these commemorations, however we are also conscious that there is still great uncertainty surrounding international travel. Therefore, we have taken the decision to pay tribute to this important generation in the safe and secure environment of the National Memorial Arboretum in Staffordshire.”

The opening of the new memorial was also shown live on the Memorial website (www.britishnormandymemorial.org), where you can now see a recording of the event.

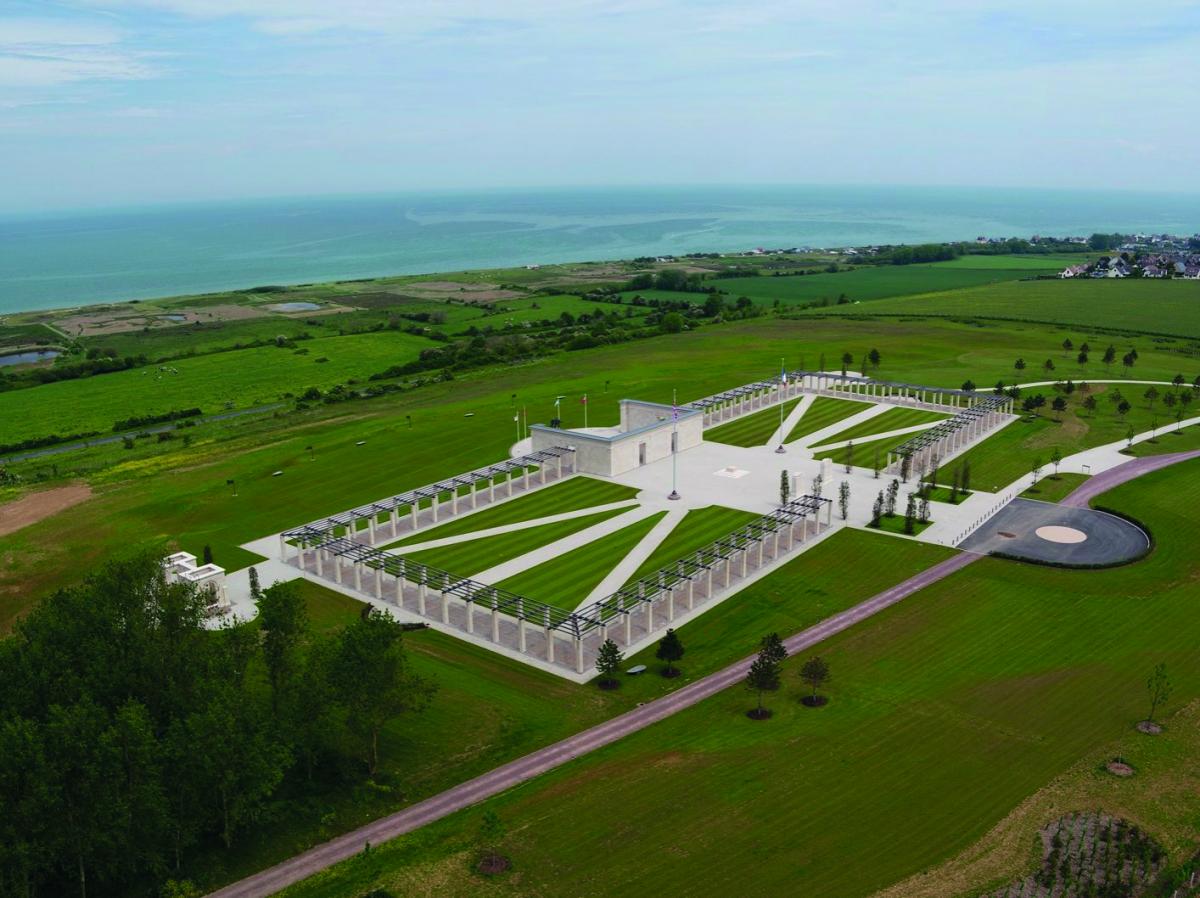

The memorial is on a 50-acre site in Ver-sur-Mer, overlooking what was code-named ‘Gold Beach’ on D-Day. The remains of a German artillery bunker borders the site to the east. The taking of the bunker earned Company Sergeant Major Stan Hollis of the 6th Green Howards the only Victoria Cross awarded on D-Day.

Gold Beach was one of three beaches where British forces landed on the morning of 6 June 1944 to begin the liberation of Western Europe.

On the 70th anniversary of D-Day in 2014, François Hollande, President of France at the time, announced that all British soldiers involved in the D-Day landings were eligible for the Chevalier de l’Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur (often abbreviated to the Legion d’Honneur), the highest French order of merit.

Those veterans who attend the D-Day service at the National Memorial Arboretum were formally presented with their medals by the French Ambassador, who attended to honour those involved in the liberation of his country from occupation by the Nazi fascists.

The British Normandy Memorial was designed by architect Liam O’Connor and built by Northern Ireland stonemasons S McConnell & Sons.

Liam O’Connor and McConnells also worked together on the Armed Forces Memorial at the National Memorial Arboretum and the Bomber Command Memorial in Green Park, London. They were both large projects, but the Normandy Memorial is their largest yet. It is built of more than 3,500 tonnes of Massangis French limestone, supplied by Polycor, the Canadian company that in 2018 bought four French quarries previously owned by Rocamat.

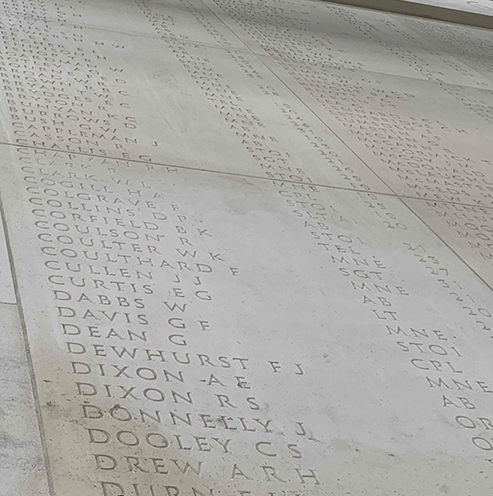

Into the stone are inscribed the names of 22,442 servicemen and women under British command who fell on D-Day and during the subsequent Battle of Normandy in the summer of 1944.

Overseeing the inscriptions was world renowned lettercutter Richard Kindersley, who was also involved with Liam O’Connor and McConnells in the lettering for the Armed Forces Memorial and the Bomber Command Memorial.

The British sculptor David Williams-Ellis, whose father was a wartime lieutenant in the Royal Navy commanding a motor torpedo boat that supported the Normandy landings, was commissioned to create the ‘D-Day Sculpture’ that occupies a prominent position in the memorial.

This is the first time the names of those who died in the battle have been brought together on one site.

The official opening of the Memorial is the culmination of nearly six years’ work by the Normandy Memorial Trust.

The memorial cost nearly £30million and was funded both by the British government and private benefactors.

The construction of a national memorial in Normandy has been a long-held ambition of D-Day veterans who were under British command. They were frustrated that while the Americans and Canadians had erected memorials to their troops who died in the battle, Britain still did not have a memorial to its forces.

At the memorial, the D-Day Wall features the names of those who fell on D-Day itself, while on the 160 post-tensioned stone columns the names of those who lost their lives between D-Day and the Liberation of Paris at the end of August 1944 are recorded, cut into the stone in McConnells workshop on two Omag CNCs.

The site also includes a French Memorial dedicated to the civilians who died during the battle.

The idea for the Memorial originated with the Trust’s Normandy veteran patron, George Batts MBE, an 18-year-old Royal Engineer (Sapper) when he landed on Gold Beach on the morning of D-Day tasked with clearing mines and booby traps. He had long held an ambition to see a defining British monument built on a single site in France to commemorate the men and women of the British armed forces and civilian services who lost their lives in the Normandy Campaign.

The idea was taken up by many other veterans, including Harry Billinge, MBE, the Trust’s veteran ambassador and fund-raiser who single-handedly raised tens of thousands of pounds in his home town of St Austell in Cornwall.

George Batts says of the Normandy Memorial: “Only those who were there on D-Day can truly know what it was like. We lost a lot of our mates on those beaches. Now, at long last, Britain has a fitting Memorial to them. I should like to express my deep gratitude to all those who have supported the Memorial and made its construction possible.”