Stone for housing: the natural choice

Stone in housing: For walls, floors, fireplaces, kitchen worktops, bathrooms, patios, outdoor kitchens... stone is the preferred choice of many home owners.

Low carbon, low maintenance, sustainable stone has a lot to offer housing. Even though the government has dropped its manifesto commitment to add 300,000 homes a year to the UK’s housing stock by the mid-2020s to try to solve a 4million home shortfall, there are opportunities in housing for many sectors of the stone industry.

Housebuilding is (and is likely to remain) an important element of the construction industry, accounting for about a quarter (£41billion) of construction output in England, according to the Construction Industry: Statistics & Policy briefing paper for the House of Commons published in December.

The number of houses being built and changing hands reflects directly on the natural stone industry, as much as on the economy of the country as a whole.

Not only do indigenous stone producers and importers supply walling stone, masonry, flooring, worktops, fireplaces and paving for the domestic sector, there is also a lot of imported stone used for kitchen worktops and floors, bathroom vanity units, shower enclosures and trays, wet room wall linings, reception room floors, walls and furniture.

And it is not just in new build that stone benefits from the housing market. There is also a lot of stone for RMI (repair, maintenance and improvement). When people move they tend to redecorate their new homes, which might well include new kitchens and bathrooms, where a lot of stone is used in domestic settings.

In interiors, the stone look is greatly appreciated. Lighter colours, particularly marble, are currently very much in vogue. But stone is also popular for the outer walls of housing, where it is often (and increasingly) a regionally appropriate locally produced stone that is used.

Of course, the popularity of stone does not go unnoticed by those who make alternatives to it. Stone masonry has to compete against precast concrete and it can be a hard battle, as Saul Harvey of Harvey Stone, producer of Ham Hill stone from Norton Quarry, says.

Harvey stone saw an increase in sales of building stone last year for the first time since the 2008 crash, although Saul says that at 100-120 tonnes a month it was only about a quarter of the amount sold in the company’s busiest months before the crash.

And, like other suppliers, he is frustrated at how easily builders change from using stone to using precast, which, of course, precast manufacturers are putting resources into encouraging them to do.

All the stone suppliers have plenty of examples of how quickly concrete masonry, such as window cills, leads to dark stains down a building. It was why planners often insisted on natural stone being used before the 2008 crash, although lessons learnt then sometimes seem to have been forgotten.

Colin Keevil at Doulting Stone complains that to add insult to injury, precasters are using his stone to make moulds for their concrete.

He says that on a single house, stone can be quicker and less expensive. But he concedes when there are dozens or hundreds of houses all using the same design elements, precast is cheaper, but it is not long before it looks cheaper. On one development of more than 150 houses there were five houses at the front that used Doulting stone and the rest used concrete copies made in casts from the Doulting originals. Colin laments: “They sort of con the public.”

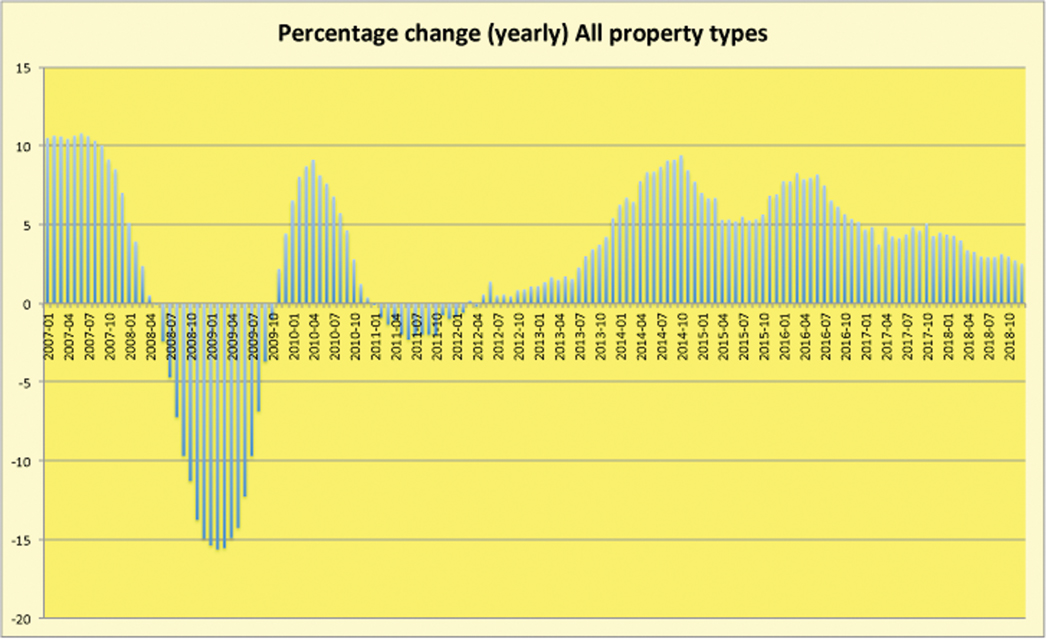

The stone industry suffered along with the rest of the building industry when house prices fell after the credit crunch of 2007-08 and building was put on hold. And it has benefitted just as much as the industry has recovered. Even the tower blocks of luxury London apartments that stand empty because they have been bought by overseas investors who seldom, if ever, visit them have granite worktops, marble bathrooms and often marble or limestone floors.

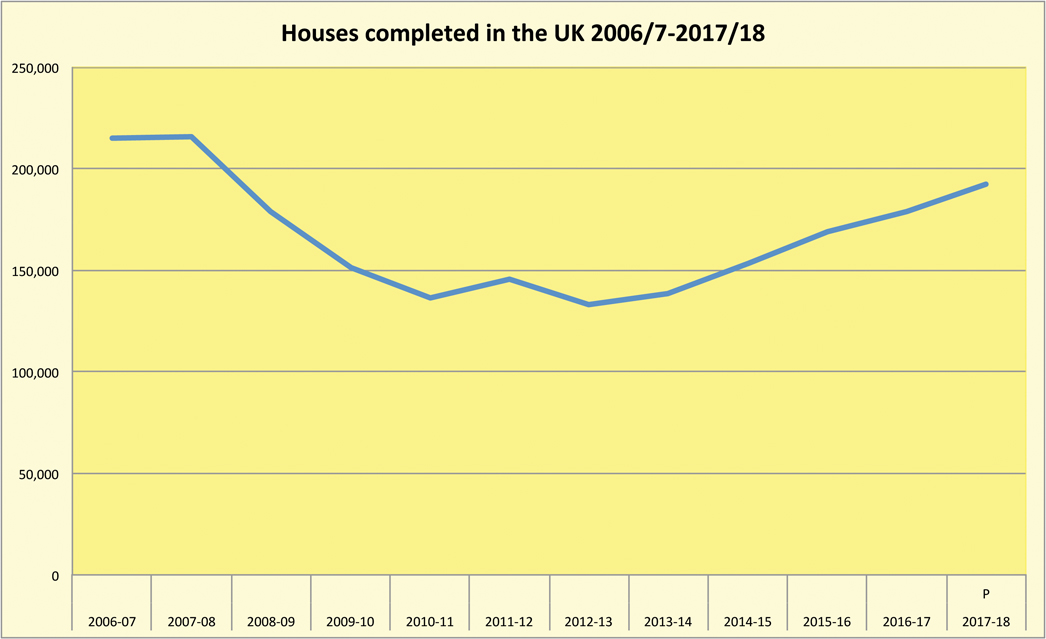

Source: Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government / UK House Price Index.

The Construction Industry: Statistics & Policy briefing paper says there were some 27.7million homes in Great Britain on 31 March 2016 – 23.7million in England, 1.4million in Wales and 2.6million in Scotland. Northern Ireland has about 800,000 homes.

The total housing stock nearly doubled (+94%) in the 60 years from 1951 to 2011. The rate of building was higher in the 1950s and 1960s than in later decades, although more houses were also demolished as slums were replaced. Nevertheless, the housing stock in Great Britain increased by 18% between 1951 and 1961 and 16% between 1961 and 1971. By contrast, it increased by 8% between 2001 and 2011.

Between 1991 and 2011 in both England and the UK as a whole the increase was 16%, although many regions saw less growth than this – the North East (9%) and the North West (11%) had the lowest growth. The South West had the largest increase in England at 22%, while Northern Ireland had the largest in the UK at 32%.

According to the Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, there were 222,190 net additional dwellings created in England in the financial year 2017-18, up 2% on 2016-17. That breaks down to 195,290 new build homes, 29,720 homes created from conversions of non-domestic buildings, 4,550 resulting from houses being split into flats and 680 others (such as caravans and boats). That was offset by 8,050 demolitions.

It says net additional dwellings in England reached a recent peak of 223,530 in 2007-08 and a low of 124,720 in 2012-13.

Elsewhere, however, the same Ministry says for the whole of the UK the number of new homes completed in 2017-18 was 192,090 – 160,560 in England, 6,660 in Wales, 17,770 in Scotland and 7,100 in Northern Ireland.

The National House Building Council (NHBC), meanwhile, says that for the whole of 2018 there were 159,617 new homes in the UK registered on its 10-year guarantee scheme, which it believes represents 80% of new builds (so the total number of new builds would be 199,500). It says the number of registrations was much the same as in 2017.

The discrepancies indicate the difficulty of collating data and are a reminder that such statistics, while helpful, remain estimates.

Nevertheless, whatever the precise number of homes being created each year might be, the government does not believe it is enough to keep up with demand.

Another House of Commons briefing paper published in December, Tackling the Under-Supply of Housing in England, says some research into the amount of new housing needed suggests as many as 340,000 units a year should be created, with the greatest need in London and the South of England. It reports that the number of new households in England is projected to grow by 159,000 a year as a result of population growth, including immigration, and fewer people living in each home, if current trends continue.

Research conducted by Heriot-Watt University published last year by the National Housing Federation (which represents housing associations in England) and Crisis (the national charity for homeless people), showed England needs an extra 4million homes.

The current Government was elected in 2017 with a manifesto pledge to meet its 2015 commitment to deliver a million new homes by the end of 2020 and to “deliver half a million more by the end of 2022.”

The manifesto said that, if elected, the Conservatives would deliver on the reforms proposed in the Housing White Paper of February 2017. After their election, the Autumn Budget that year set out an ambition “to put England on track to deliver 300,000 new homes a year”.

Housing Minister Kit Malthouse has reiterated that ambition. “We’ve not built enough homes in this country for the last three decades. We’re turning that around as we work towards our target to build 300,000 properties a year by the mid-2020s.”

The industry that would have to deliver that level of output questions its own ability to do so and the National Audit Office (NAO) has said the Government cannot achieve its target without significant changes to the planning process.

The NAO says the planning system is not dealing with applications effectively because councils use outdated information to calculate how many new homes are needed. Under the current system, it says, no more than 250,000 homes a year can be delivered.

The National Federation of Builders (NFB) says the NAO is right to point out the need to reform the planning process (the NFB has been calling for changes to it for years) but says the NAO does not tell the whole story.

It says the Government needs to do three things in order to build enough new homes:

- update the method used to assess local housing need

- ensure local plans are robust and allocate deliverable sites

- reform the process of planning permission.

Homes England is already helping local authorities reform planning by working with local authorities directly to meet demand, speeding up the planning permission process and helping developers access finance after they secure planning permission.

Richard Beresford, chief executive of the NFB, says: “We cannot build 820 new homes every day unless we are realistic about demand. Decades of failure are no excuse. We need action, not reviews. The Government must learn from Homes England’s experiences.”

Rico Wojtulewicz, head of housing and planning policy at the House Builders Association (HBA), adds: “Even if we correctly assess demand, unless we allocate deliverable sites and grant permissions, shovels won’t get into the ground. We have tinkered for years, it’s time for the Government to get real and actually reform the entire planning process.”

Planning is not all that stands in the way. Nick Horton of Forest of Dean Stone Firms, which supplies walling for housing (although it is a relatively small part of the firm’s output) sums up succinctly what many in the industry say: “We haven’t got the money, we haven’t got the bodies and we haven’t got the materials, either.”

Cllr Martin Tett, Local Government Association (LGA) housing spokesperson, points out: “The last time this country built homes at the scale that we need now was in the 1970s, when councils built more than 40% of them. With millions of people on social housing waiting lists, councils want to get on with the job of building the new homes that people in their areas desperately need.”

The LGA had been calling on the government to scrap the housing borrowing cap on councils for years, which it did in an announcement by Prime Minister Theresa May at the Conservative Party Conference last year.

The Prime Minister said that “solving the housing crisis is the biggest domestic policy challenge of our generation”. She said that scrapping the government cap on how much councils can borrow against their Housing Revenue Account assets to fund new developments, as well as opening-up the £9billion Affordable Housing Programme to councils, would enable them to build again.

In her speech, the Prime Minister said the government “will build the homes this country needs”.

Buoyed by its success, the LGA is now campaigning for councils to be allowed to keep their ‘Right to Buy’ receipts from selling council houses.

Cllr Tett says: “Allowing councils to keep 100% of their Right to Buy receipts is the next step to delivering the renaissance in council housebuilding we need as a nation.”

The LGA commissioned Cambridge Economics to assess what the financial implications would have been if 100,000 government-funded social rent homes had been built in each of the past 20 years.

It concluded that: all housing benefit claimants living in the private rented sector could have moved to social rent homes by 2016; the housing benefit claimants who moved from the private rented sector would have had £1.8billion in extra disposable income over the period; the Government would have had to borrow an additional £152billion in 2017 prices to build the homes, but every pound spent would have generated £2.84 in return.

The problem remains, of course, of where the labour and the materials to build the homes will come from, even if the money can be sorted out.

Already even low value items such as bricks and cement are being imported, usually from Europe, and the industry, especially in London, has relied on a supply of labour that often comes from eastern European countries and which is drying up. The government reported last year that there had been a net loss of slightly more than 100,000 people from the former eastern european countries.

Even if local authorities can manage to help the government on its way to 300,000 new homes a year, social housing does not typically use a lot of stone... although stone has been used even for social housing, even new build.

Andy Smith at Glebe Stone’s Ancaster quarry says a housing association built nine social housing units in his Ancaster stone on a new estate where all the other houses were brick. He assumes it was because they were closest to a stone church.

He says he normally spends the winter stockpiling building stone but has not had an opportunity to do so this year because demand has been so high, helped, no doubt, by the generally mild weather. He said Glebe would be producing to meet the orders it has already received well into April and demand would normally be increasing by then.

At Lovell Stone Group, James Hart has the same experience. Lovells is one of the growing stone groups operating Hartham Park Bath Stone underground quarry as well as opencast quarries producing various stones including Purbeck. In the past six years investment by the Group has doubled its capacity but James says: “We produce 1,000m2 a week and we haven’t got a single square metre in stock.” He says demand in the past 18 months has been more buoyant than he has known it in the past decade. “It’s difficult to get bricks and guillotined building stone is a low cost product.”

British stone producers are certainly keen to point out the advantageously low maintenance lifetime costs of using a sustainable, low carbon local building material, especially when other materials are in short supply.

Sawn, cropped and tumbled walling stone is mass produced by many quarries these days, so often compares reasonably well with brick, even on the initial purchase price. And it can be (and is) laid by brickies at much the same pace as bricks.

Some stone producers have geared up specifically for the anticipated growth of the housing market. In the previous issue of Natural Stone Specialist we featured Johnston Quarry Group with its associated Bath Stone Group. A new cutting shed with five wire saws and two walling lines has been opened at Johnston’s Great Tew quarry in Oxfordshire to supply the building industry.

Nicholas Johnston, the owner, told Natural Stone Specialist: “We should have more natural stone going into housing and less energy inefficient brick, which is not even that much cheaper and the houses don’t sell as well.

“It’s important that we keep telling and selling the stone industry story. A stone house, designed and built sensibly, should be the norm in towns and villages where stone is the traditional building material.

“With the current uncertainty surrounding Brexit, we continue to believe that the UK is significantly behind on its new housing delivery and that further opportunities for natural stone use present themselves in wider residential, commercial, civic and restoration applications.

“We are working hard across both Johnston Quarry Group and Bath Stone Group to ensure we meet the aspirations of our clients and we are organising ourselves now for the growth in the UK economy in the future.”

Nicholas believes there will be a lot more optimism and confidence once leaving the EU is behind us.

An active housing market, in both new build and RMI, benefits many parts of the stone industry, with a lot of imported stone being used on interiors as well as largely indigenous stone used for walling.The project pictured above is Logie Point in Jersey, which was Commended in the Natural Stone Awards in December. Chinese White Woodvein limestone supplied by SFS Stone has been used.